Number 582 September 2019 Edited by Stephen Brunning

HADAS DIARY – LECTURE AND EVENTS PROGRAMME 2019

Tuesday 8th October 2019: To be arranged. Unfortunately Lyn Blackmore has had to cancel due to work commitments. The lecture was to have been on MOLA excavations at Tottenham Court Road 2009 to 2010.

Tuesday 12th November 2019: Shene and Syon: A Royal and Monastic Landscape Revealed. Lecture by Bob Cowie.

Sunday 1st December 2019: HADAS Christmas Lunch at Avenue House. 12:30 – 4 p.m. including full Christmas dinner. Price and booking form will follow.

Lectures start at 7.45 for 8.00pm in the Drawing Room, Avenue House, 17 East End Road, Finchley N3 3QE. Buses 13, 125, 143, 326 & 460 pass close by, and it is five to ten minutes walk from Finchley Central Station (Northern Line). Tea/coffee and biscuits follow the talk.

——————————————————————————————————————- Obituary: Derek Renn By Peter Pickering

Derek Renn was our only surviving Life Vice-President, and was site director of the Arkley kiln site dig in 1959/60. He died on 31st May, at the age of 89. Derek went to school at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School in Barnet and served for 44 years in the Government Actuary’s department. He was a Fellow of the Institute of Actuaries and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Actuaries, and was made a CBE in 1992 for his work at the Government Actuary’s Department. At the same time he was an expert on castles; among his many publications about them (including eleven guides) his book ‘Norman Castles in Britain’, published in 1968, stands out. He co-authored (with John Kent and the late Anthony Streeten) a report on the excavations at South Mimms Castle. Derek also wrote on other topics, from letterboxes in Leatherhead and a flint axehead from Hampshire to scratch dials in Surrey churches (not to speak of many articles in the Journal of the Institute of Actuaries.). He became a Life Vice-President of HADAS in May 1996, but this was but one among the posts that he held. He had been a member of the Council and Treasurer of the Society of Antiquaries, on the Council of the Surrey Archaeological Society, President of the London & Middlesex Archaeological Society and of the Leatherhead and District Local History Society, and Honorary Vice-President of the Royal Archaeological Institute. He was also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and of the Royal Statistical Society. A truly eminent man.

Ted Samms Clay Pipe Collection.

Text by Andy Simpson with photographs by Bill Bass.

The Ted Sammes pipe collection continues to yield surprises. I am continuing to research and write the detailed analysis, but in the meantime he herewith provides a little ‘taster’ text.

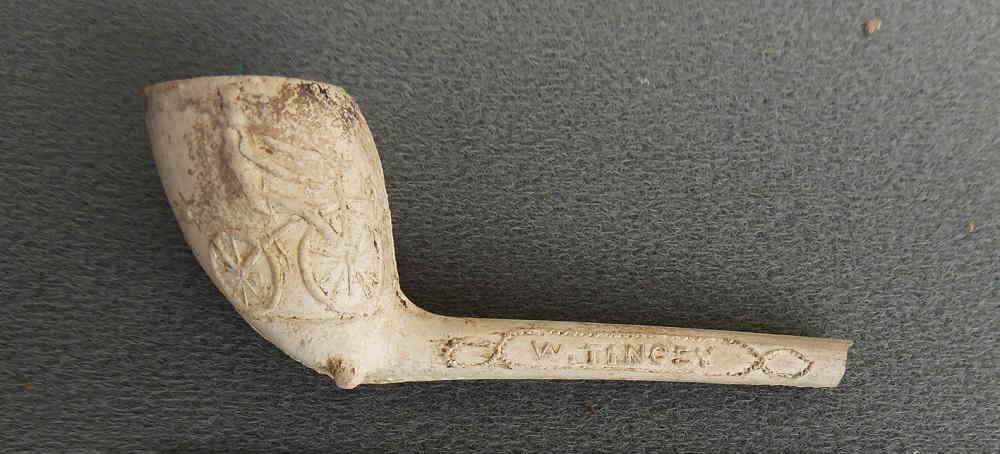

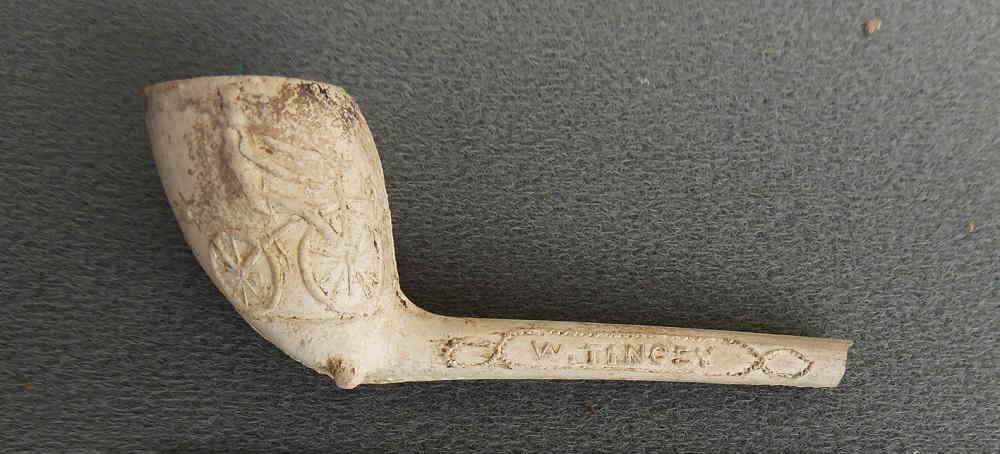

This rather splendid cyclist appears to be riding a ‘Velocipide’ of the years around 1819-1820 – popularly known as the ‘Hobby Horse’ or “dandy horse,” after the foppish young Regency men – ‘dandies’ who often rode them- often on the pavement to the annoyance of pedestrians. No change there, then…at least then the fashion ended within the year, after riders on pavements were fined two pounds – equivalent to a salutary £135 at today’s values!

The pipe itself however (Sammes List No 34) appears to be of much later date, around 1900, and is marked as being a product of well-known pipe maker W. Tingey of Hampstead. Perhaps it was made for a cycling club, popular at the time?

http://www.cyclemuseum.org.uk/Hobby-Horse.aspx

A Hidden Landscape: Romney Marsh Emma Robinson

“The world, according to the best geographers, is divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America and Romney Marsh” (The Ingoldsby Legends by Richard Harris Barham).

David and I first visited Romney Marsh in the 1970s when I was doing a botanical research project comparing the characteristics of British marshes. So when we were offered the opportunity to join a “Hidden Histories” tour of the Marsh led by local resident and practicing archaeologist Dr Christopher Cole (who is also the Director and Project Manager of Aldington and Romney Archaeology) we jumped at the opportunity to visit again. It is thus of no surprise that we were given the privilege of visiting both current and past sites of their excavations. We were based at the remarkable Mermaid Inn in the ancient town of Rye. The Mermaid has been an inn since the 12th century although it was substantially rebuilt in the mid-15th century. The owner kindly gave us a special tour of the Inn of which she is immensely proud also telling us something of the people associated with the building (including smugglers) and the many ghosts which haunt the place. A warning – those of taller stature need to take great care in walking about what is a truly unpredictable building with many low doors and passages to navigate.

Romney Marsh is a unique corner of England. It has been associated with famous people, fascinating stories, smuggling and strange mysteries since Roman times. The earliest archaeological evidence of human habitation is during the Bronze Age on what would have originally been islands. Therefore, it is not surprising that a central theme of the Marsh’s story is the ongoing battle to drain the land and keep the sea from reclaiming it back. The reclamation of Romney Marsh started in Roman times and by Saxon times fishing villages and ports began to develop. Eventually towns such as New Romney, Hythe, Rye and Winchelsea emerged which were to become vital to the defence of England. In 1155 Henry II granted a royal charter which led to the formation of the Cinque Ports of Sandwich, Dover, Hythe, New Romney and Hastings. In the royal charter Rye and Winchelsea were named as ‘Ancient Towns’. However, the ‘Great Storm’ of 1287 changed the face of the landscape of the Marsh for ever. It diverted rivers, left towns without harbours, abandoned Rye on top of an inland cliff and washed Old Winchelsea into the sea.

But this was not the last disaster. Originally the Marsh had been an intensely farmed area having rich productive soils but the area was particularly badly hit by the plague in the 14th century and sheep then became dominant agriculturally since they could be farmed by a much smaller work force. As a result many smaller communities began to disappear and are now often only marked by their church ruins set amongst sheep pasture. Malaria also took its toll. Monuments in churches record many sad stories of families loosing family members particularly children to what was then known as ‘Marsh Ague’.

During the Napoleonic period there was considerable concern about the possibility of invasion and the Military Canal was built. This had the effect of making the Marsh an island. The Canal is a superb piece of engineering designed for defence. It was fortunately never needed – but the area’s military importance continued until WWII.

I have so far said nothing of the churches of the Marsh. This could be the subject of an article alone. Evidence was found of remains of churches and places of worship from Roman times, the Anglo-Saxon period until today. For those like David and I who enjoy a good ‘church crawl’ we highly recommend a visit to the Marsh. It will also be of interest to some HADAS members that we were impressed to find that most now had good toilet facilities. Smuggling was an important local industry and many of the churches we were told were adapted substantially to hide the contraband.

We heard stories about the on-going battle between smugglers and the Revenue Men and secret tunnels of many sorts.

We should add that we found a good range of fascinating old pubs which served some great local beer. We also enjoyed the local seafood. Those of us more interested in cakes were not disappointed either.

No HADAS trip would ever be complete without a railway visit. The Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway is a 15 inch (381 mm) gauge miniature railway and the only miniature railway in the British Isles ever to have been incorporated under the Light Railways Act 1896, and has been operating along the Romney Marsh coast since 1927. It runs for 13.75 miles from Hythe to Dungerness. The locomotive at the platform when we arrived was the Winston Churchill in a splendid livery. We were pleased to be introduced to her although her loud whistle did make some of us jump. The shingle beach is of great botanical interest. When we visited in mid- July it was a purple haze of vipers bugloss – the colours of which were set off by the sea pea in all shades of pink from white. The pretty bungalow gardens having richer soils had a fine display of plants typical of shingle beaches.

We do not recall if HADAS has ever visited Romney Marsh and the other fascinating landscapes along the adjacent Kent and East Sussex coast? There is a remarkable diversity of heritage sites and archaeology which helped form our national past. It is truly one of Britain’s most intriguing regions.

Secret Rivers exhibition at Docklands museum Jim Nelhams

HADAS ran our first “bus pass” outing in June 2017 with a visit to the Docklands Museum, part of the Museum of London, to see an exhibition about the archaeology of Crossrail (see newsletter 558 – September 2017).

On 27th July, 16 of us repeated the journey to the museum for an exhibition about the London Rivers which are now underground. It was noted that some would not have gone on their own but enjoyed going as part of the group.

The exhibition is titled “Secret Rivers”, and acknowledges support from The Worshipful Company of Plumbers, The Worshipful Company of Water Conservators and The Water Conservation Trust. How appropriate!

The routing of Crossrail, now designated the Elizabeth Line, was complex needing to thread its way between other underground railways and underground services such as telephones, gas and water supplies and sewers. I did not realise at the time, but this also included a number of rivers which are now underground often functioning as sewers. The exhibition covers the rivers Fleet, Lea, Tyburn, Walbrook and Westbourne north of the Thames, Effra, Neckinger, Wandle to the south, and traces their routes.

Several rivers have sources within the Borough. The Fleet has two main sources separated by Parliament Hill, one near the Vale of Health and forming Hampstead Ponds, and the other in the grounds of Kenwood House and leads to Highgate Ponds. These two sources unite just north of Camden Town.

Barnet and Mill Hill form another watershed. Two of the main sources of the River Brent, (not covered by the exhibition), Dollis Brook and Folly Brook, emerge at Mill Hill, combining near North Finchley station before flowing south to meet Mutton Brook, which rises at Hampstead, close to Henlys Corner. At the Welsh Harp, they are also joined by the Silk Stream which rises near Canons Park before flowing through Colindale.

Streams to the north of Chipping Barnet go northwards to join the River Lea, and the Pymmes Brook, which flows through East Barnet, heads eastwards through New Southgate, Palmers Green and Edmonton, also joining the Lea.

This FREE exhibition continues until 27th October. ——————————————————————————————————————–

Clitterhouse House Farm Dig. Roger Chapman

By the time this newsletter reaches you the 2019 HADAS excavation at the moated medieval farm at Clitterhouse will be over. However we can bring you the results of a couple of days site watching whilst the café building where we will be excavating was demolished.

The site lies within the gateway entrance to the farm. The contractors removed the café and concrete slab to reveal a few centimetres down a cobbled surface, small pieces of Victorian pottery and glassware plus lots of construction and building materials together with an as yet unidentified feature. It was a promising start and full details will be published in a future edition of the newsletter. Meanwhile here are two photographs from the dig.

Local list Peter Pickering

At last Barnet Council has published in draft the new Local Heritage List, which is to replace the old Schedule of Buildings of Local Architectural or Historic Interest. The new list was compiled with the help of local volunteers, several of whom were HADAS members. It runs to over four hundred pages, compared with the previous twenty-eight. Not only are there far more (over 1200) structures (including milestones etc as well as what we usually think of as buildings) on it, but there are also now rather good pictures and verbal descriptions of each. The result is not perfect – it is not fully searchable, for instance – but it is a considerable achievement, and will help planning for many years to come.

Imperial Rome’s North-West Frontier: Can It Explain Britannia and London’s Role within the Province? Melvyn Dresner

Harvey Sheldon’s lecture after our Annual General Meeting on 11th June 2019 was an attempt to examine whether Rome’s initial interest in Britain and later, its acquisition of the province of Britannia, which it held for three and half centuries, could be explained by the requirements of the Imperial frontier on the Rhine.

This Rhine frontier, a boundary made necessary by Julius Caesar’s incorporation of much of Gaul within the Empire in the mid-1st century BC, was established by Augustus from about 35 BC onwards. Though barbarian incursions through the Rhine, into Gaul and beyond, occurred, especially from the mid-3rd century AD onwards, it survived as a viable Imperial frontier until the first decade of the 5th century. It’s unlikely to have been a coincidence that its end came at much the same time as Honorius, the Emperor in the West was informing authorities in Britain that they needed to look to their own defences.

Sheldon suggested that David Mattingly’s “An Imperial possession: Britannia in the Roman Empire” (2006) is not un-typical of writers of the last 30 years in explaining the Claudian AD 43 invasion as, more or less, a combination of the current internal situation in Britain and its effect on Imperial prestige.

In Sheldon’s view, the relationships initiated by Augustus with Britain from about 30 BC onward, reflected in the writings of his contemporary, the political-geographer Strabo, were intended to ensure that sufficient goods and raw materials were available from Britain while the frontier was being established under difficult circumstances, and then beyond, as its permanence became accepted. There is archaeological evidence of imports from the Roman world including metal and fine pottery as well as foodstuff containers. More politically important, both Augustus and Strabo indicate native princely contact with Rome. Though Strabo lists products exported from Britain to the continent it may not be exhaustive. Grain, wool, leather, livestock and raw metals or finished products, as well as slaves and hunting dogs, might be expected to be in great demand.

Whatever necessary political stability had been built-up between Augustus and Britain’s princes, had broken down, by about AD 40 and the invasion was made necessary by threats to supplies, reflecting the importance of these goods and raw materials to the survival of the Rhine armies and their dependents and the consequent viability of the frontier itself.

In Sheldon’s view a major objective of the establishment of Britannia, from AD 43 onwards, was to ensure that the Province, on the western flank of the frontier was secure and could supply whatever raw materials, foodstuffs and other supplies were needed on the Rhine and for campaigns beyond.

Conquering, then holding Britannia, involved the stationing of initially four, later three, legions on the province, as well as the creation of London, an urban centre with substantial numbers of administrators present. The literary and archaeological evidence for London suggests that, throughout the three and a half centuries of Roman rule, it served as the central place where many functions relating to the governance of the province were carried out.

Sheldon suggested that London’s landward walls were erected soon after the mid-3rd century AD. Unlike many urban centre walls in Gaul, they appear to have been built unhurriedly, with newly quarried and transported material and around the perimeters of settlement rather than as a hurried defence of a small nucleus. More recently found similarly constructed sections of the London riverside wall might suggest that the whole circuit was erected in the later 3rd century. This was perhaps at the time of the Gallic Empire when, following destructive barbarian incursions into Gaul, the Rhine frontier was under threat and the armies in Britain, Spain, Gaul and Germany were in revolt against the Imperial government. Though the London walls, as well as those around many other towns in Britain, might also have been built after the Empire was reunified in the early 270’s, they might indicate that the purpose was similar. In the less benign Imperial circumstances that existed from the mid-3rd century onwards, there would have been an increased need to of keep Britain secure both as a productive source of supplies and of military reinforcements available for deployment to an increasingly threatened Rhineland.

Check your change Jim Nelhams

In September, our trip to South Wales will include a visit to the Royal Mint.

For many years, commemorative coins have been struck by the Royal Mint, but most of these have been coins which do not go into general circulation, such as crowns. However, since 1973, our fifty pence coins have from time to time had events marked on the reverse. 1973 was the year when we joined the Common Market, and the coin issued at the time shows nine hands clasped in a circle signifying the nine community members at that time. Since then, the size of 50p coins has been reduced.

In 1998, special issues marked the 50th Anniversary of the National Health Service, and in 2005, the 250th anniversary of Johnson’s Dictionary.

More recently, attention has included children’s literature although other coins have also appeared. 2016 saw a coin to mark the 150th birthday of Beatrix Potter with coins of Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddle-Duck, Mrs Tiggy-Winkle and Squirrel Nutkin, followed in 2017 by a different Peter Rabbit picture, Tom Kitten, Jeremy Fisher and Benjamin Bunny, and in 2018 yet another Peter Rabbit, Flopsy Bunny, Mrs Tittlemouse and the Tailor of Gloucester.

To mark the publication of his first book in 1958, 2018 saw Paddington Bear on two coins, one showing the station after which he was named, and the other in front of Buckingham Palace, and on 13th August 2019 (hot off the press) come two more showing Paddington at the Tower of London and St. Pauls’ Cathedral.

Some of the coins are also issued by Royal Mint in solid silver coloured with enamel, but these are not for circulation and cost rather more than 50p.

And reverting to 1973, the plan is to issue a new commemorative coin to mark our Exit from the European Union.

Meanwhile, a lot of these special coins have been limited issues and are acquiring rarity value. Some are already for sale on Amazon and Ebay, so check your change carefully.

Cerne Abbey Revisited (Part2) Charlie Leigh-Smith

I’ve recently attended a landscape surveying course run by Stewart Ainsworth and Al Oswald, both ex-RCHME* surveyors at Epiacum, a Roman fort in Cumbria. This was an enjoyable weekend with archaeology students, lawyers, a doctor, retired folk and even a judge working in teams to detect the lumps and bumps, just by using your eyes. But this was relatively easy once you got your eye in and knew the context, because the site had been abandoned, robbed out and had never been put under the plough in this vast open space, nor built over. That’s not the case in many parts of the countryside where rural farming and pressures of urban development on top of cultural changes have altered the landscape, and made archaeological and historical detection difficult. Much of these changes came about in the Victorian era.

With this background in mind, I add some observations to research at Cerne Abbey in Dorset. Here as referred in an earlier issue the water management for milling was reviewed through what remained. Abbeys, towns and villages had to be self-sufficient.

A name in the village like Mill Lane was a clue to the past where narrow street patterns suggested these hadn’t changed for a long time. Mill House, a Victorian building was the obvious site of the medieval mill (at the back, remains of a medieval building outhouse with discarded grinding stones set into the ground) but no obvious signs remained in the house itself. It was a family house.

However, outside was an open space beside which was evidently the partial remains of a sturdy medieval brick wall. Chatting to the new owner who had just dug out the water race in the yard immediately beside the wall, showed me how it pointed towards the river about 8m distant. It was clear that the mill from historical documents was still operating up to the 1950’s, when water had been channelled round the back of the house to a point near the medieval wall 4m above ground level. This would have been a vertical water wheel which was common in medieval England, a Roman design probably reintroduced from France. But how had the river – only a brook some 60m upstream – come to provide this strong motive power that turned a heavy wooden wheel was interesting because it demonstrated how ancient technology was used, and human ingenuity.

The power of this river water today, seen and heard at the open sluice gate located before Mill House is frighteningly powerful and so noisy you can’t hear yourself speak. The answer to how this power was achieved came by bending the river course around and along a hill line towards the mill which, only a brook some 70m upstream, was there widened considerably so the volume of water increased. Flowing on a gentle (5 degree) decline, at about 10m before Mill House the channel narrows armoured by rocks. To compensate, the sub-surface deepens and then drops towards the sluice which has the effect to pull the river water behind to form a body about 1/2 sq. thick to drop about 2m to a pool below, there to re-join the original river course.

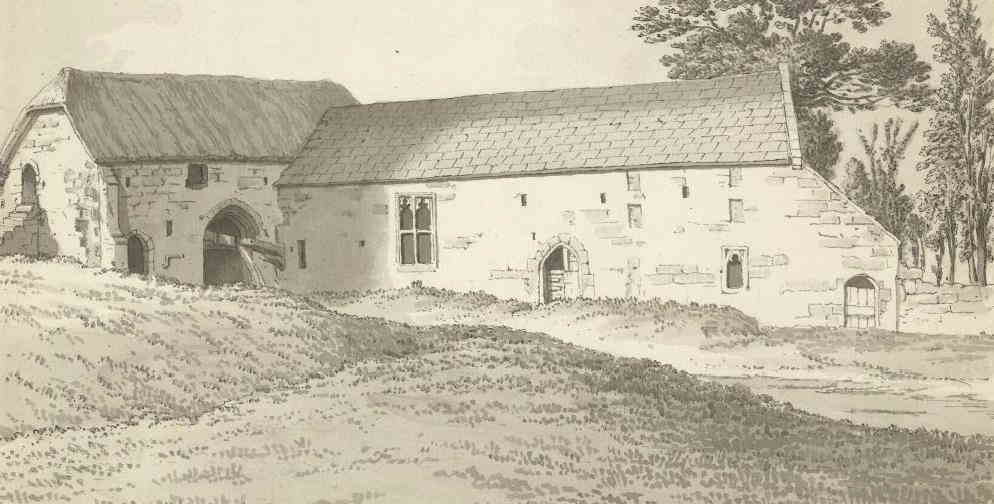

Although the medieval mill would likely have occupied the site of Mill House, an excursion to Abbotsbury Abbey proved useful. Here beside Abbotsbury Hotel are the remains of the medieval mill built by monks from Cerne in the 13th century. It became known as the Malthouse. Inside you can see the scraping of the 12 foot (4m) wheel on the stone wall. The plan and size of the mill house and its arrangement flowing left to right would have been very similar to the mill along Mill Lane at Cerne Abbey. Moreover, the plan would fit in the available space.

The Malthouse, Abbotsbury. The standing building on the left is the mill. (Open source)

But according to Exon Domesday* Cerne Abbey possessed two mills. We have one built by the abbey for the village on the Mill House site; the second had to be inside the abbey. But where? The site of a mill pond near the Barn situated in the working area (non-religious) zone of the abbey was a notable feature – today an oblong hollow in the ground some 20m long 4m wide.

Land up the valley where springs rise to form the River Cerne was bought up / gifted which is where the abbot’s manor was located. The abbot owned land all the way to the abbey grounds. Thus, when I was scratching my head wondering how water from the river was made to go up hill to the abbey some 2m above, because over millennia the river had furrowed a deep ravine into the soft greensand geology, the answer was the monks had built an arm that scooped about half the river water (there, still a brook) into a 1.5m channel that tracked the river as it fell (using surface topography) which bent round into a sizeable pond – the mill pond. This scoop made of Victorian brick but with older bricks at the footing was still visible, hidden amongst undergrowth about half a mile upstream. To prevent too much water in flood conditions accessing the man-made channel, the volume of water was managed by an 18 inch access hole in the brickwork. Excess water was returned to the river. Clearly these Benedictine monks knew what they were doing.

This surface channel wasn’t at first obvious from old OS maps because the linear feature shifted its line at right angles about every 100m, a device evidenced at other medieval abbeys, used to catch debris before it got anywhere near the pond and mill downstream. But this second mill itself was nowhere to be seen. The area had been a farm in Victorian times. Buildings seen on an estate map and OS map, all demolished.

It was fortunate that at the time when I with my team we were visited on site by Lord Digby who later told me that as a young boy running around the dairy shed (near the mill pond) he’d seen a wooden wheel cut into the floor at the far end. He described it as about 6ft in diameter although only a quarter visible above the floor. A half size undershot water wheel! This was just what was needed as it resolved a water flow shown on an estate map drawn up for Mr Rivers (later Pitt Rivers) exiting an unnamed building near the pond. The site of the second mill that served the abbey was resolved.

Interestingly, the operations of a water mill haven’t changed for centuries and it’s a marvel that water power – like wind power we use today – is a free natural resource. Improvements were made over time. One of these was a device that tinkled a bell, warning the miller that the despite the

wheel having been physically disengaged, something had happened to make it turn. A small bell was fitted called a damsel to warn the miller, and this is how according to the senior miller at the Weald Museum Chichester the saying goes … ‘saving a damsel in distress’.

Now, that’s not quite what I had thought it meant.

Further Reading

Aston, M., 2000 Monasteries in the Landscape. Amberley Publishing

Aston, M., 1988 Medieval fish, fisheries, and fishponds in England (Vol.1) BAR

Bond. J 2001 Monastic Water Management in Greta Britain; A Review in Monastic Archaeology Papers on the study of Medieval Monasteries, pp.88-136. Edited by Keevill, Aston, & Hall

Bowden, M., 1999 Unravelling the landscape. Tempus.

Graham, A. H. 1986 The Old Malthouse, Abbotsbury, Dorset. in DNHAS* (Vol. 108 pp.103-123)

Magnusson, R 2001 Water Technology in the Middle Ages. Johns Hopkins University Press

DNHAS: Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society.

RCHME: Royal Commission for Historic Monuments in England. Now part of Historic England

Exon. Abbreviation for Exoniensis. The original document is in Exeter Cathedral Library (MS 3500).

Other Societies Eric Morgan

MEETINGS / TALKS

Thursday 5th September, 8pm. Pinner Local History Society. Village Hall, Chapel Lane Car Park, Pinner HA5 1AB. Watford’s Bronze Age Hoard. Talk by Laurie Elvin – a local archaeologist on treasures discovered in 1960. Visitors £3.

Thursday 19th September, 7.30pm. Camden History Society. Camden Local Studies and Archive Centre, Holborn Library, 32-38 Theobalds Road WC1X 8PA. Medieval Camden. Talk by Dr Ellie Pridgeon. Visitors £1.

Friday 20th September, 7pm. COLAS. St Olave’s Church, Hart Street, EC3R 7NB. From Roman Activity East of the Forum to Post-Medieval Guildhall. Archaeological investigations at 120 Fenchurch Street. Talk by Neil Hawkins (PCA). Visitors £3.

Thursday 3rd October, 8pm. Pinner Local History Society. AS ABOVE. Outstation Eastcote to GCHQ. Talk by Ronald Koorm. Code Breaking in WW2 & more. Visitors £3.

Thursday 10th October, 1pm. Society of Antiquaries. Burlington House, Piccadilly W1J 0BE. Armistice & Archaeology at Sea. Talk by Aiden Dodson (FSA). FREE but limited places. Pre-book via www.sal.org.uk/events or telephone 020 7479 7080. Lasts 1 hour.

Friday 11th October, 7.45pm. Enfield Archaeological Society. Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane, junction of Chase Side, Enfield EN2 0AJ. Finding Enfield’s Fallen. Talk by Martin Lambert. Visitors £1. Refreshments, Sales and information from 7.30pm.

Monday 14th October, 3pm. Barnet Museum and Local History Society. St John The Baptist, Barnet Church, junction of High Street/Wood Street, Barnet EN5 4BW. The Old Roads of Barnet. Talk by Dennis Bird. Visitors £2.

12

Friday 18th October, 7pm. COLAS. AS ABOVE. Grave Goods: Objects and Death in Later Prehistoric Britain. Talk by Neil Wilkin (British Museum). Visitors £3. Refreshments.

Wednesday 23rd October, 7.45pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society. North Middlesex Golf Club, The Manor House, Friern Barnet Lane N20 0NL. Street Names of Soho and the West End. Talk by Rob Kayne. Visitors £2. Refreshments & Bar.

Saturday 26th October, 2-5pm. Willesden Local History Society. St Mary’s Church, Neasden Lane NW10 2TS. An afternoon of Medieval History. Joint meeting with the Monumental Brass Society. Talks about the History, Monuments and Brasses of Willesden’s only surviving Medieval Building. Refreshments provide.

Saturday 26th October, 3pm. Barnet Museum and Local History Society. AS ABOVE. Mapping of London from the Earliest Times to 1800. Gillian Gear Memorial Lecture given by Peter Barber (President of Hornsey Historical Society). Visitors £2.

Thursday 31st October, 7.30pm. Finchley Society. Drawing Room, Avenue House (Stephens House & Gardens), 17 East End Road, Finchley N3 3QE. History of Finchley Charities. Talk by Roger Chapman (HADAS Treasurer). Non-Members £2.

AND FINALLY…. This year the Bank of England will mark 325 years since it was founded. To celebrate this milestone, the Bank of England Museum is holding a temporary exhibition until 29th May 2020. Open Mon-Fri 10am to 5pm (Excluding Bank Holidays). Last Entry 4.30pm. FREE. See https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/museum/whats-on/2019/325-years-exhibition for further details.

With many thanks to this month’s contributors:

Bill Bass, Roger Chapman, Melvyn Dresner, Charlie Leigh-Smith, Andy Simpson, Jim Nelhams, Eric Morgan, Peter Pickering, Emma Robinson, Stewart Wild

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chairman Don Cooper 59, Potters Road, Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8440 4350)

e-mail: chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary Jo Nelhams 61 Potters Road Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8449 7076)

e-mail: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer Roger Chapman 50 Summerlee Ave, London N2 9QP (07855 304488)

e-mail: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec. Stephen Brunning 22 Goodwin Ct, 52 Church Hill Rd,

East Barnet EN4 8FH (020 8440 8421) e-mail: membership@hadas.org.uk

The October 2019 Newsletter Editor will be: ROBIN DENSEM