Avenue House

The story of the Woodhouse College building before it became a school in 1922

The first mention of buildings on the site of Woodhouse College is in 1655. It is in the probate of the will of Allen Bent of Friern Barnet. The will, dated 15th January 1655, refers to three tenements “called the “Woodhouses” that are now in the several occupations of William Moore, William Amery and Abraham Wager” according to the Prerogative Court Of Canterbury – Berkeley Quire Number 91, Transcription by C O Banks/Wills.

In 1743 James Patterson, turner, of the Parish of St George the Martyr in Middlesex came into possession of “all those two messuages called or known as the Woodhouses with one ground room under the said messuages” (Middlesex County Record Office). These two tenements came into the possession of Thomas Collins through his wife on the death of her father James Patterson in 1765 “ James Patterson bequeaths his tenements in Finchley to his daughter Henrietta Collins, wife of Thomas Collins” according to the Gentleman’s Magazine 2nd November 1827. They had married on 19th November 1761. The third tenement was in the possession of John Bateman, a wine merchant, who in The List of Finchley Freeholders lives at “Woodhouses”. In his will, proved in 1776, he orders his executors to sell his house and gardens as soon as possible; and it was sold in 1778 to John Johnson who in 1784 transferred it to Thomas Collins; this is described as “one of the messuages one of the Woodhouses”. Thomas Collins became possessor of all three Woodhouses.

By 1754 one or perhaps a number of them was called Wood House as seen on Rocque’s Map of Middlesex. A mansion was built there between 1784 and 1798 according to Barnet Local History Library (Acc. 6140/1) becoming the centre of an estate created at inclosure of Finchley Common. At the inclosure in 1816, the Marquis of Buckingham and Sir William Curtiss, major local landlords, were allocated 45 acres and 39 acres respectively. Thomas Collins bought both their allocations. Here is an artist’s impression of the house in 1797.

Thomas Collins was an ornamental plasterer who worked for, and was a friend and partner of Sir William Chambers, a noted architect and interior decorator. He, with George Andre and Robert Browne, were executors of Sir William Chambers will (National Archives Oxford Hey/v/10). In 1815, Thomas Collins and Sir Nathaniel Conant, giving their addresses as Woodhouses Finchley, are listed as subscribers to a religious book by William Martin Trinder. Sir Nathaniel Conant died in 1822.

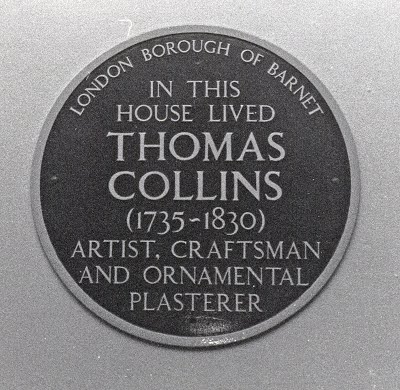

Thomas Collins was born in 1735 and died in 1830. According to his obituary published in the Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle from January to June 1830

Volume C being twenty-third for a new series, Part the first, edited by Sylvanus Urban Published in London by J B Nichols and Sons:

May 3. Aged 95, Thomas Collins, Esq. of Berners Street, and of Finchley, Middlesex, F.S.A.

“If a long life, spent in the exercise of all the duties of society, claim a record, this memorial cannot better be merited than by the late Mr. Collins. His career in life commenced in business; he undertook, with the late Mr.White and others, the continuation of the excellent houses in Harley Street, Marylebone, which they accomplished successfully. In the pursuits of business he did not neglect the cultivation of his mind, so he became a desirable member of the society of Dr Johnson, Sir William Chambers, the architect (to whom he was executor), Mr Baretti, Major Rennell, Rev. Dr. Burney, Mr Strahan, Mr Nichols and others. He was fore of the jury at the trial of Lord George Gordon, and the writer of this article has heard the late Lord Erskine express how much he owed to his firmness and discrimination in that important event. He afterwards became an active magistrate of the county of Middlesex, and the father of the vestry of St Marylebone. Mr Collins had the happiness to be united to a lady whose views in life were quite accordant with his own; she lived till the end of the year 1824, a bright example of conjugal affection and urbanity. Such a life employed in the exercise of virtue, was attended with considerable wealth; this he distributed among his relations, without forgetting the friends with whom he associated”.

There are many references to Thomas Collins of which the following are a sample:

“….. John Papworth (1750-l799), a stuccoist frequently employed by the office of works in the time of Sir William Chambers and his partner Thomas Collins, received payments amounting to £7,915 2s 8d for plasterwork at Somerset House.” (Roscoe, 2009)

“The mansion which became known in the nineteenth century as Stratheden House was designed by Sir William Chambers for the politician and army contractor John Calcraft the elder (1726–72), who took a long lease from the freeholders, William and John Shakespear. It was built in 1770–2 on a joint contract by Chambers and the decorative plasterer Thomas Collins.” (Greenacombe, 2000)

“There is a picture in the hall of the Chancellor’s painted by Pyle, said to represent an architect Henry Keene who has summoned all his artificers (fifteen of them) to dine with him so that they can examine his plans and point out any problems and/or errors. Among those present is Thomas Collins who is described as: “Thomas Collins, Plasterer.. This gentleman was the only survivor of the fifteen, at the time when Mr Nichols bought the picture. He acquired a large fortune by building, particularly in Harley Street, and he latterly resided in Berners Street and at Finchley. He became a magistrate for Middlesex, and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. He died in 1830, at the age of ninety-five, being then the father of the vestry of St Marylebone” (Nichols, 1839)

Thomas Collins, 95, was buried in St Mary’s cemetery, Finchley on 12th May 1830.

He is recorded as being of Berners Street, St Marylebone; and Woodhouses, Finchley.(see St Mary’s Finchley Burial record). His wife, Henrietta, had died at “Woodhouses” on 2nd November 1824 aged 87” (according to the “Gentleman’s Magazine”, November 1824 p476) and was buried on the 8th November at St Mary’s Finchley according to the burial register.

On the death of Thomas Collins, Woodhouse passed to his great niece Margaret Collins Jennings.

According to the National Archives ACC/0395/ 21 – 31 Aug. 1830, there was a marriage settlement between Margaret Collins Jennings of Finchley and William Lambert Esq. of Monmouth which included Wood Houses in Finchley and much other property. They were married on 23rd September 1830. William Lambert was a J.P. for Middlesex.

Sometime between 1841 and 1860 the separate house was pulled down.

Then there is the information from the census returns:

Then there is the information from the census returns:

1841 William Lambert (aged 40) and his wife Margaret (aged 35) were living at Wood Houses (one house occupied and 2 uninhabited) – his occupation was given as independent. They had four servants. They had no children.

In the 1851 & 1861 The Lamberts were not at home but their servants were – it is referred to as 64 Wood House Lane on the census.

In 1859 there was an auction of some of the freehold land by Moss and Jameson at the Torrington Hotel (according to the Morning Post, dated 29th April 1859)

1871 census William Lambert (74) and Margaret (69), he is a magistrate and landowner. They have Lady’s maid, a cook, a housemaid, a kitchen maid, a butler, coachman, a gardener, an under gardener, and a gardener labourer. There is a widow Caroline C Castle née Jennings(53) living with them. She had been married to the late William Henry Castle.

William Lambert dies 4th October 1874 and leaves an estate worth £50,000 to his wife. His wife Margaret dies 7th November 1877 and leaves an estate worth £100,000 to two of her nephews – Edward Castle and Michael Castle – living with her. (UK probate records).

The house and estate was then sold to G W Wright-Ingle whose family came from St Ives in Huntingdonshire. Wright-Ingle reconstructed and enlarged the house in 1889 employing the architect E W Robb of St Ives. The down pipes are still marked 1889 in 2012. From the plans the lobby and the front and back rooms of the west end of the house were not rebuilt. G W Wright Ingle’s wife had a daughter at Woodhouse on 27th September 1891 according to the London Standard dated 1st October 1891.

In the 1891 census the estate is occupied by George W Wright Ingle, his wife two sons and a daughter and five servants.

1901 census George W Wright Ingle and his wife are still resident.

1905 Electoral Register shows George W Wright Ingle living at Woodhouse.

1911 census a Mr Thomas Needham is the occupier.

One of the roads on the estate is called Lambert Road after William Lambert. Castle Road was called after the widow who lived with them.

Hilton Road and Fen-Stanton Avenue are called after the two villages near St Ives, Huntingdonshire where George Wright-Ingle came from and Ingle Way is also called after him.

This is view of the rear of the house in about 1900.

In 1910 the house came into the possession of the Busvine family according to Percy Reboul (1994). In the same book Margaret Busvine describes living at Woodhouse.

Here is Mr Busvine in his car outside the house in about 1910

Middlesex County Council agreed to buy the house in 1915 but only “when peace was restored” which unfortunately meant that the building suffered some neglect before becoming a school in 1922.

This is a Post-WWII aerial view of the House.

For the full story of the school from 1922 to 1949, see Percy Reboul’s book: See details in the Bibliography

This is the blue plaque to Thomas Collins on 1st floor of the College.

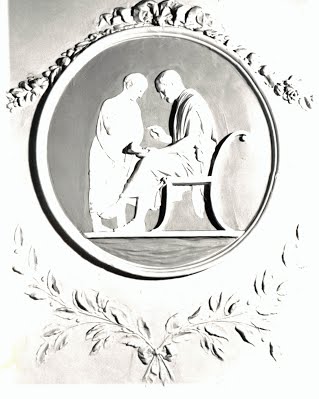

It seems a long shot but do the following photos of decorative items currently (2012) in the house indicate survivals of Thomas Collin’s work?

This is one of two ornamental plaster plaques in the vestibule of the house perhaps by Thomas Collins

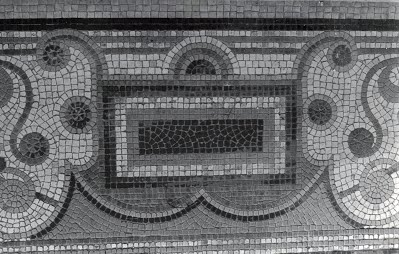

There are also some lovely floor mosaics and door fittings as follows:

It would be lovely to believe that these are survivals from Thomas Collin’s occupation.

Acknowledgements

Percy Reboul for giving permission to use copies of the photographs in his possession.

Yasmine Webb of the Barnet Archives for her help.

Bibliography

Greenacombe, John (ed.) 2000. A Survey of London Vol.45, Kinghtsbridge. London/English Heritage

Nichols, John Gough. 1839. “The Hall of the Chancellors” Hammersmith, London/ Nichols private press.

Reboul, Percy. 1994. By Word and Deed: A Chronicle of Woodhouse School 1922 – 1949. Finchley, London/ Friends of Woodhouse College.

Roscoe, Ingrid. 2009. A Biographical Dictionary of Sculptors in Britain, 1660-1851 USA/Yale University Press

Comments

You do not have permission to add comments.

Sign in|Recent Site Activity|Report Abuse|Print Page|Powered By Google Sites

No. 553 APRIL 2017 Edited by Peter Pickering

HADAS DIARY – Forthcoming Lectures and Events.

Lectures are held at Avenue House, 17 East End Road, Finchley, N3 3QE, and start promptly at 8pm, with coffee/tea and biscuits afterwards. Non-members: £1. Buses 82, 125, 143, 326 & 460 pass nearby and Finchley Central station (Northern Line), is a 5-10 minute walk away. Tuesday 11th April 2017: Where Moses Stood A Talk by Robert Feather

‘Where Moses Stood’ is the subject of a power point presentation, relating the culmination of intense research and four years exploration in the Sinai Desert. It describes what is claimed to be the real story of the progression of the Exodus from Egypt to the Promised Land; the exact location of Mount Sinai – the place of the giving of the Ten Commandments; the remains of part of The Tabernacle; the Copper Snake Moses used to ward off poisonous serpents; the 2,600-year-old bones of the scapegoat used to carry off the sins of the people into the desert; and ………a sacred item once carried in the Ark of the Covenant.

Robert Feather trained as a metallurgist and has written a number of books on history, archaeology, and Middle Eastern subjects.

Tuesday 9th May 2017 The Cheapside Hoard – Hazel Forsyth

Tuesday 13th June 2017 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

Monday September 25th to Friday September 29th. 2017 HADAS trip to Frodsham Tuesday 10th October 2017 The Curtain Playhouse Excavations, – Heather Knight, MOLA Tuesday 14th November 2017 – The Battle of Barnet Project – Sam Wilson.

February Lecture Report- London Ceramics at the Time of the Great Fire By Jacqui Pearce FSA Report by Deirdre Barrie

Our speaker was Jacqui Pearce, Pottery Specialist for Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA)). She set the scene with the turbulent events of the 17th century: civil war, the execution of the king, the Great Plague and the Great Fire.

Ceramics experts have a virtual snapshot of what ceramics were in the homes and inns of London on 1st September 1666. This is because all the cesspits (great sources of archaeological finds) were sealed by the debris of the Great Fire on the 2nd. (Pepys wrote a near journalistic account of the Fire in his Diary.)

Pottery imports found in London are often shown in 17th century still life paintings by artists in the Low Countries; Jacqui made good use of such art in her slides, (e.g. ‘Still Life with Fish’ by Wallerant Vaillant).

For food preparation, there were cauldrons with two hollow handles (so the cook’s hands did not get burnt); pipkins with one handle and maybe a lid for slow cookery, and small dishes, say for something with eggs. Chafing dishes kept food warm, with coals in the base and a lid, or you could put a pewter plate on top. Skillets were like frying pans; porringers were bowls with one handle to spoon things out of. Items for the table included salts (open dishes for salt), mustard pots and flower vases – these last were for middle class society.

Posset pots had a hollow handle through which you sucked the fluid. Posset does not sound very appetising – it was milk curdled with wine or ale, and sometimes spiced. Flasks for wine could be set in wicker containers (rather like the old-style Chianti bottles we remember).

For serving up there were platters – shallow plates. In the late 16th century ceramic and pewter was used instead of the old wooden trenchers. Chargers were huge plates for display, to sit on a side table or cover an empty hearth. In 2012 one such was found in a Southwark ditch.

Items for heating and lighting included ceramic candlesticks, and fuming pots for banishing nasty smells, then thought to be a cause of disease.

Among the miscellaneous items found were round moneyboxes, associated with theatres (hence the term ‘box office’); watering pots for flowers, and bird pots, which you put on the side of the house for sparrows – then you ate the young. Large ceramic dishes with concentric rings were for putting on the ground and feeding chickens. Novelty items included a puzzle jug with lots of holes, and a cat-shaped jug.

What did it all look like? Where did it come from? London ware (jugs etc.) was red. Surrey/Hampshire ware often had yellow or green glazes, and the main centre for its manufacture was Farnborough. A German potter moved to the area, and brought new ideas and techniques.

Slipware had a pattern poured on to the unbaked pottery, or ‘iced’ on. Metropolitan Ware came from Harlow in Essex, and Staffordshire slipware is white with red decoration. When wet, the clay with its two colours was combed with a feather to give an attractive ferny pattern. Some plates had a ‘piecrust’ ridged edging. Such plates are occasionally dated and one of the Museum of London’s early such finds says ‘1630’ in big letters.

Imports included North German Weser ware and white wares from North Italy, which may have been desirable for their fluted patterns and clean purity. But Ligurian majolica could have colourful, even garish, decoration of leaves, fruit or animals. Polychrome vessels were coloured and decorated with geometric patterns of, say, pomegranates or tulips.

White tinglazed vessels were used for sack (white wine) and also for medical drugs. Imported Dutch blue and white ware often showed Chinese influence, for in the mid-17th century Chinese porcelain was coming in via Portugal and the Netherlands. Such items were found in pothouses in Southwark.

Drink came in jugs of local red ware. There were copies of Bellarmine or Bartmann jugs, with their big round bodies and bearded faces on the stem. (These were sometimes used in apotropaic magic as ‘witch bottles.’)

Beer was served in brown Essex ware, but black vessels were popular during the Commonwealth. (A pub during the Commonwealth must all in all have been a sombre place.)

With the return of Charles II, vessels took on a religious and patriotic tone, with portraits of the king, and the words ‘KING’ and ‘GOD’ featured in large letters. The first coffee house, ‘The Jampot’, where coffee was drunk from bowls, opened in 1652. The remains of the big imported storage jars for coffee are occasionally confused with Roman amphorae.

More personal ceramic objects included ceramic bedpans and vessels for a close-stool. Chamberpots are often found in cesspits – dropped there by accident. In Spitalfields 96 were retrieved from only one site!

Early Ceramic Clay Pipes. Don Cooper

On a recent trip we visited the Archaeological Museum in Mazatlán in Mexico. Mazatlán is on the Pacific coast of Mexico in the state of Sinaloa. The Archaeological Museum is small but has about 500 ceramic artefacts from pre-Spanish cultures, mostly Aztec.

One of the surprises for me was clay pipes. As you can see the dates on the first exhibit represent a wide range (1200 to 1531AD).

These pipes showed no obvious signs of having been smoked and there was no indication of the specific site they came from. The curator said that they had come the southern part of the state. The three in the photo above are ornate and suggest that there was a considerable typology involved. What was being smoked I couldn’t establish but I suspect it was tobacco.

It seems that before the Spanish conquistadors came there was an industry making a variety of pipes which perhaps indicates that a considerable number of the population smoked.

And then pipe smoking and manufacture came to Europe…….

Jane Austen and Canals – continued Liz Tucker

In my summary of our boat trip from Bath, I made the flippant remark that I could find no reference to canals in Jane Austen’s novels.

Subsequently, I read David Nokes’ biography, where he states that she went for walks along the canal with her uncle, when her family first moved to Bath in 1801. The canal did not open until 1810, by which time she had left the city, but construction began in 1789, so maybe she walked along the partcompleted route, admiring the brawny navvies digging it out.

When I checked a few websites, I found that she had written in a letter ‘my long-planned walk to the Cassoon’ – the caisson lock at Coombe Hay, on the Somerset Coal Canal, which led into the Kennet and Avon.

The websites I looked at were ‘Jane Austen in the Age of Steam’, and ‘Down the Kennet and Avon Canal with Jane Austen’. I should be interested to have more information!

Rail Sightings by Andy Simpson

The good thing about our HADAS weeks away is the sheer variety of interests covered, and sometimes the chance to nip off to follow personal interests – as regular trip participants are only too aware in my case, whether it be railways or bus museums!

A case in point was our visit to Bristol for Brunel’s magnificent steamship, SS Great Britain. Bristol Harbour is a familiar haunt for me, and when we all spilled off the coach by the Great Britain, I looked down the harbour side and sure enough a distant wisp of steam a half-mile or so away indicated something was afoot on the short Bristol Harbour Railway at Princes Wharf/Wapping Wharf, even on a weekday, so I ‘made my excuses and left’. Only in Bristol can you actually take regular rides on a dockside steam railway at the heart of a modern city, just one mile west of Bristol Temple Meads station!

It transpired that resident 0-6-0 Saddle tank ‘Portbury’, built in 1917 by Bristol makers Avonside Engine Co Ltd for the Inland Waterways and Docks Board as their No.34, and currently bearing their original livery, had been steamed specially to shunt fellow railway resident 0-6-0 tank ‘Henbury’, also built in Bristol by Thomas Peckett & Sons in 1937, for a boiler lift as part of her overhaul back to working order. Fortified by a sausage sandwich from my favourite harbourside café, a couple of hours were spent watching some gentle shunting before Henbury’s cab and boiler were lifted by one of the four still-operational dockside cranes outside the ‘M Shed’ industrial and social museum – always worth a visit. After sale to the Bristol Corporation Docks Committee in about 1920, Portbury (and Henbury) worked the Bristol docks lines until 1964 when they were happily set aside for preservation at the former Bristol Industrial Museum. https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/m-shed/ https://bristolharbourrailway.co.uk/ www.bristol-rail.co.uk And at the rail crossing giving access to Claverton pumping station later in the week, Jon Baldwin was also distracted by the odd passing class 66, or ‘Sheds’ as they are lovingly known to the enthusiast fraternity…

And the distractions just kept coming! Having had a good look around Wells Museum, it was off to track down the remaining traces of the railways of Wells – from three lines and stations to not a yard of track by 1969. At least Wells (Tucker Street) goods shed survives in good condition as just about the only visible relic following its closure in 1963.

And the distractions just kept coming! Having had a good look around Wells Museum, it was off to track down the remaining traces of the railways of Wells – from three lines and stations to not a yard of track by 1969. At least Wells (Tucker Street) goods shed survives in good condition as just about the only visible relic following its closure in 1963.

http://www.railwells.com/history.html

Current Archaeology Conference Peter Pickering

Once more I spent a recent weekend at the Annual Conference of Current Archaeology (this year celebrating its fiftieth anniversary). Very well attended by the magazine’s subscribers from all over the country – remarkably few from London. Here are some of the highlights.

Once more I spent a recent weekend at the Annual Conference of Current Archaeology (this year celebrating its fiftieth anniversary). Very well attended by the magazine’s subscribers from all over the country – remarkably few from London. Here are some of the highlights.

Michael Walsh of Cotswold Archaeology talked about the wreck of HMS London in the Thames estuary off Southend. HMS London was the flagship of both the Commonwealth and the Restoration navies, and went down when on the way to fight the Dutch. Finds include cannon, timbers, small weapons, a personal sundial and lots of clay pipes. Was smoking on board near quantities of gunpowder a good idea – and was it in any way connected with the explosion that did for the ship? Digging trenches in the sea-bed 25 metres down with ships passing overhead sounded an uncomfortable form of archaeology, but the rewards have been great.

There were two papers relating to writing. Roger Tomlin described with enthusiasm several of the

Roman writing tablets found in advance of the construction of a building for Bloomberg (formerly Bucklersbury House of Mithras fame). And Matthew Champion told us about the fast-growing number of graffiti found in churches (over 6,000 in Norwich Cathedral alone) and in other buildings as well (remember those we saw in the Bradford-on-Avon barn?). There are, it appears, many drawings of demons, but only one has yet been found that may be of an angel. Animals drawn seem all connected with hunting – there are none of sheep, cows or pigs. Ships remain very frequent – even in churches far from the sea.

What was most striking about the papers was the number which described the revisiting of old excavations. HADAS must have started a trend with what we have done with Ted Sammes’ dig. Roberta Gilchrist has been going over a century of scantily published (but well archived) investigations at Glastonbury Abbey. Richard Bradley has re-excavated a Scottish stone circle (Croft Moraig), and Colin Haselgrove the Iron Age site at Stanwick (Queen Cartimandua’s capital?); Martin Millett and

Rose Ferraby have worked on Aldborough (Isurium Brigantum), and Paul Booth on Dorchester-onThames. To generalise wildly, it appears that earlier excavations were done competently and archived well, if not fully published, but that modern techniques (geophysics; vastly improved radio-carbon dating; photography by drones) enable much more information to be elicited. And of course interpretations have changed – Stanwick, for instance, was originally dug by Mortimer Wheeler who often saw things in a military way (remember how he thought he had found the Britons who died defending Maiden Castle against the Roman invaders.)

There were also accounts of dramatic new digs – Great Ryburgh with its coffin burials, an Iron Age settlement in Dorset, Little Carlton in Lincolnshire with lots of coins, styli and bells, and the remarkable Must Farm in the fens, showing how much stuff Bronze Age people owned. For those who prefer their archaeology gruesome, there was a study of bog burials and the horrible end these people came to; a higgledy-piggledy mass grave in Gloucester (victims of the late second-century plague?); and the rather more orderly burials of seventeenth century plague victims found during the Crossrail construction.

The final talk was an enthusiastic presentation of the successes of the Portable Antiquities Scheme by Kevin Leahy; he emphasised in particular how metal detectors often got there before deep ploughing destroyed previously unknown sites for ever.

Further archaeological watching brief work at RAFM Pt. 2 Andy Simpson

On Monday 20 February 2017, site manager Steve Johnson reported a further spread of material exposed during turf stripping of the former ‘Helicopter Landing Area’ at the western edge of the Hendon site. The turf has now mostly been removed for expansion of the car parking area during ongoing site landscaping work funded by the HLF.

The Curator of Aircraft made a visual inspection and walked the newly exposed area in an approximate grid pattern. Conditions were fine and dry.

A further small selection of post-medieval material was made. The greatest spread of material was at the southern end of the exposed area closer to a pathway to the former pedestrian entrance.

These included a further single small piece of clay pipe stem; body fragments of ribbed stoneware jar; a fragment of blue glass poison/medicine bottle; wire-reinforced window glass; blue transfer-printed earthenware and china, including plate rim, and tile; a one pound coin dated 1990 (probably lost in the former picnic tables area) ; fragments of white glass jar; one complete white glass jar with moulded ‘Pond’s England’ on the base, presumed to be for Pond’s Face Cream; and a complete glass jar, possibly for writing ink.

Items noted but not retained included quantities of red brick fragments and domestic ‘bathroom’ tile, along with the ash/clinker filled cuts of more modern field drains cut into the natural clay, which lies close to the surface below the turf line and some clay subsoil.

This material is comparable to that found near Hangar One during the initial site watching carried out on 6th February, previously reported. It certainly supports the notion that considerable areas of dumping of modern, twentieth century material has occurred on parts of the site as the result of demolition, and there could be redeposited Blitz rubble. The few fragments of clay pipe stem – now four in all – are the only potentially pre-c.1850 items, suggesting little historic activity in the immediate area, which would be logical bearing in mind it was largely pasture land until the creation of the airfield.

Further material, mostly mid-twentieth century glassware, was recovered by the contractors on 22nd February and kindly passed on for assessment. This included two horseshoes, identified by horseowning archives Curator Belinda Day as one for a shire horse or similar heavy breed, and a smaller ‘standard breed’ example – which is slightly bent, indicating it may have come off in an accident.

Further to the mention in the previous report of the November 1992 watching brief by MOLAS on the adjacent site of the then-new Divisional Police Station/Area Headquarters (GPW92, TQ2193 9011, c. 50m above OD), the evaluation took place over two weeks, and five trenches were excavated in shallow spits through 30cm of topsoil and black cinders- possibly a make-up layer – (again comparable to the RAFM site) down to the surface of the natural London Clay; land drains in cinder and gravel fills similar to those found at the museum site in 2017 and a few sherds of 19th-20th century pottery, mainly blue and white china – as found at the museum site – a single sherd of tin-glazed ware (TGW, possibly 18th century in date) and a single clay pipe stem were recovered; landscaping and truncation during and after the life and closure of the aerodrome may have led to destruction of any earlier features, and this may be the case at the Museum site also.

It would appear that this area, and much of the Manor of Hendon (held by Westminster Abbey), was heavily wooded in medieval times, with settlement on these low-lying claylands limited to isolated farms and the occasional small hamlet. By the mid eighteenth century with the removal of the woodlands the area was open fields, in use for both some arable and (mainly) meadow/pasture, the latter for sheep and cattle, with haymaking an important industry to feed the horses of London via Cumberland Market in London, the fields being manured by material coming in the opposite direction from London!

By 1780 the fields beneath the future aerodrome were held by the Broadhead family of Church Farm at Hendon Church End (latterly the former and much lamented Church Farm Museum, housed in the original seventeenth-century farmhouse, which still stands), who still held them in 1843.

In 1869, the then-480-acre Church Farm was acquired under lease by Andrew Dunlop; background can be found at http://www.balean.net/dunlop.html

Andrew Renwick points out that the freehold was owned by Lt Col Theodore Francis Brinckman, from whom local aviation pioneers Everett and Edgcumbe & Co Ltd negotiated a lease, along with two other local landowners. They were then given permission to clear the land and erect a shed to house their new (and unsuccessful) monoplane; this work may have started late 1909 but had certainly started by February 1910. The new The London Aerodrome Company Limited leased and cleared more land later in 1910, the uncompleted flying ground opening on 1st October 1910. The perhaps better-known Claude Grahame-White doesn’t enter the local scene as an aircraft builder and operator until 1911.

Colindale had begun to build up in the early 1890s, and, after felling trees and clearing ground/hedges in what was then pasture land, preparation of the airfield commenced as mentioned above, some 700 metres west of the settlement at Hendon Church End with its Roman and Saxon/medieval history lying on an area of free-draining gravels.

Church Farm was a dairy and haymaking farm until the first half of the twentieth century, and also bred Clydesdale Horses – heavy plough horses. Perhaps the shire horse horseshoe found is an echo of this?

See; Grahame Park Way, Hendon London Borough of Barnet An Archaeological Evaluation Museum of London Archaeology Service January 1993

See also; Aerodrome Road, Hendon London Borough of Barnet Archaeological Desktop Report Oxford Archaeological Unit November 1996

The Last Hendon Farm The archaeology and history of Church End Farm Hendon and District Archaeological Society

To The Manor Born Five Good Reasons To Visit Hendon The Fascinating History of Hendon Greyhound Inn, Hendon August 1996

A Near Miss for HADAS? Bob Michel

Had the society visited Bradford on Avon a few months earlier, they would have doubtless been in a state of shock and awe as they witnessed the skirmish on the bridge mentioned by Micky. OK not the actual skirmish but an authentic and thrilling re-enactment by Sir Marmaduke Rawdon’s Regiment of Foote, being a Royalist regiment of the English Civil War Society (new recruits warmly welcomed). Who? Well think of the Sealed Knot, only better. As you can see from the photograph, those who saw our efforts must have felt that they had been transported back in time! And giving practical effect to Micky’s reference to the former chapel on the bridge, we made good use of the lock-up to secure the rebels’ dastardly officer on his surrender to superior forces. Another victory for His Majesty, ‘Huzzah’, although things didn’t turn out so well for him in the end of course. Incidentally, your correspondent is the kneeling musketeer, second from the left, in the oddly dyed jacket.

Photo credit: Helen Spence, Rawdon’s Regiment.

Long Barrows Back in Fashion after 5000 Years! Stewart Wild

Long Barrows Back in Fashion after 5000 Years! Stewart Wild

A friend of mine, knowing my interest in archaeology and anything underground, has sent me details of a new development just a couple of miles from where he lives in southwest Cambridgeshire. Willow Row Barrow in Hail Weston is a hand-crafted stone burial mound built as a resting place for cremation ashes and is thought to be the first one to be built in the county for over 4,500 years.

This is the second such barrow in England; the first was built in 2014 outside the village of All

Cannings, near Devizes in Wiltshire, and was the idea of Tim Daw, a local farmer and steward at Stonehenge. It was designed and built by Martin Fildes, stonemason Geraint Davies and others at a cost of £200,000. After receiving considerable media coverage it was fully subscribed in eighteen months. Details and pictures may be seen at www.thelongbarrow.com/news.

Encouraged by the success in Wiltshire, the team behind the construction, now a company called Sacred Stones, has built the second one in Cambridgeshire, close to St Neots. Local folk were invited to visit on an Open Day, and my friend says he was impressed by the level of craftsmanship.

The past inspires the future

The mound has been built by a team of master stonemasons using stones on top of natural stone just like the dry-stone walling technique. The circular structure is covered with earth and has a natural material matting on top to protect it and as a base for wild flowers. The stone-fronted entrance looks like a modern-day Fred Flintstone cave house.

Inside there is no natural or electric light; the interior is lit with candles alone. The circular chamber is eleven metres wide and eight metres high with an impressive central circular stone corbelled roof. The barrow is built of limestone that came from Buckinghamshire. A team of six to eight craftsmen took six months to complete the structure.

The burial ashes are to be placed in ‘pigeon-holes’ which are effectively stone shelves with compartments for urns – there are also some circular holes where ashes are rolled up into felt pouches and put inside. There is space for 345 ‘customers’ in what is definitely a niche market!

Similar barrows are planned in Herefordshire and Shropshire and other counties too. Further information and pictures may be found at www.sacredstones.co.uk.

Other Societies’ Events Eric Morgan

Thursday 20th April. 7.30pm. Camden History Society. Burgh House, New End Square. NW3 1ET. The search for Eleanor Palmer (d. 1558), benefactress of Kentish Town. Talk by Caroline Barron. Visitors £1.

Friday 21st April. 7pm. City of London Archaeological Society. St Olave’s Church Hall, Mark Lane EC3R 7BB Excavations at 100 Minories. Talk by Guy Hunt. Visitors £3. Refreshments after.

Thursday 27th April. 10.30am. Mill Hill Historical Society Visit to the Worshipful Company of Drapers. Meet at Drapers Hall, Throgmorton Avenue EC2N 2DG for a guided tour and learn about their history and the work they carry out. Book by Tuesday 11th April. Cost £6. Cheque (payable to Mill Hill Historical Society) and S.A.E to Julia Haynes, 38 Marion Road Mill Hill London NW7 4AN. Contact Julia Haynes on 020-8906 0563 or email haynes.julia@yahoo.co.uk giving email address or name and telephone number and the number of places requested.

Thursday 27th April. 8pm. Finchley Society. Avenue House 17 East End Road, Finchley, N3 3QE. The Regents Canal and its History. Talk by Roger Squires. Visitors £2.

Thursday 4th May. 8pm. Pinner Local History Society. Village Hall, Chapel Lane car park, Pinner HA5 1AB. Bells and Baldrics. Talk by Tony Adamson (A history of Morris dancing from a Morris Man). Preceded by AGM. Visitors £3.

Sunday 7th May. 2.30pm. Heath and Hampstead Society. Meet in Hampstead Lane N6 by entrance to Kenwood walled garden and stables (210 bus stop Compton Avenue/Kenwood House). Athlone House, Cohens Fields and the Upper Highgate Ponds. Walk led by Thomas Radice. Lasts approx. 2 hours. Donation £5.

Monday 8th May. 3pm. Barnet Museum and Local History Society. Church House, Wood Street, Barnet (opposite museum). The Hunting of Hepzibah. Talk by Jim Nelhams (HADAS Treasurer). Visitors £2.

Wednesday 10th May. 7.45pm. Hornsey Historical Society. Union Church Hall, corner Ferme Park Road/Weston Park N8 9PX. Aeronautical happenings in London’s Lea Valley. Talk by Dr Jim Lewis. Visitors £2. Refreshments, sales and information from 7.30pm.

Thursday 11th May. 7pm. London Archaeologist. Institute of Archaeology 31-4 Gordon Square WC1. AGM and Annual Lecture. An important Roman period site in the City recently excavated by Pre-Construct Archaeology. Neil Hawkins.

Saturday 13th May. 2pm. Enfield Society Historic Buildings Group. Guided Heritage walk round the Clay Hill area. Meet outside St John the Baptist church (W10 bus, from outside Enfield

Town Post Office in Church Street at 1.25pm). Walk ends at Stratton Avenue (W10 bus back to Enfield Town at c.3.45pm or 191 from stop by Forty Hill roundabout). For free tickets send contact details with S.A.E to Clay Hill Heritage Walk, Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane Enfield EN2 0AJ stating how many tickets (maximum 4), or for email tickets email heritagewalks@enfieldsociety.org.uk.

Monday 15th May. 8pm. Enfield Society Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane/junction Chase Side,

Enfield EN2 0AJ. London’s Railway Termini – Part 2, South-west. Talk by Roger Elkin, covering Paddington, Victoria, Charing Cross, Waterloo, Blackfriars, Cannon Street and London Bridge.

Wednesday 17th May. 7.30pm. Willesden Local History Society. St Mary’s Church Hall Neasden Lane NW10 2TS (near Magistrates’ court). Retail Reminiscences. Talks given by Society members about shopping locally in Willesden high streets before supermarkets.

Wednesday 17th May. 8pm. Edmonton Hundred Historical Society. Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane/junction Chase Side, Enfield EN2 0AJ. A Child’s War – Growing up in WW2 Talk by Mike Brown.

Thursday 18th May. 10.30am. Finchley Society. Visit to the London Canal Museum and Boat Trip on the Regent’s Canal. Meet at the Museum, 12-13 New Wharf Road, King’s Cross N1 9RT. Cost £10 (pay in advance) including tea/coffee and refreshments on arrival and an hour’s boat trip along the canal and an introduction to the Museum. 24 places available. Contact Rosemary Coates on 020-8368 1620 or rosemary.coates@hotmail.co.uk.

Friday 19th May. 7.30pm. Wembley History Society. English Martyrs’ Hall, Chalkhill Road, Wembley HA9 9EW (top of Blackbird Hill, adjacent to church) Spitalfields – a Village of change. Talk by Colin Oakes. Visitors £3. Tea/coffee 50p in interval.

Friday 19th May. 7pm. City of London Archaeological Society. St Olave’s Church Hall, Mark Lane EC3R 7BB Ancient Merv – a forgotten city on the silk roads of Central Asia. Talk by Tim Williams (Institute of Archaeology). Visitors £3. Refreshments after.

Tuesday 23rd May 10.35am. Mill Hill Historical Society Visit to Middle Temple including walking tour and option for lunch. Meet at Temple tube station for a short walk past 2 Temple Place and into the grounds of Middle Temple. Cost £8 for tour; plus £30 (£35 with wine) for lunch in Middle Temple Hall. Also optional visit after lunch to Temple Church (£3). Booking instructions as for 27th April visit above.

Wednesday 24th May. 7.45pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society. North Middlesex Golf Club, The Manor House, Friern Barnet Lane N20 0NL. Holidays by Rail Talk by David Berguer. Preceded by AGM. Visitors £2. Refreshments and bar before and after.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Morbi vitae dui et nunc ornare vulputate non fringilla massa. Praesent sit amet erat sapien, auctor consectetur ligula. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Sed non ligula augue. Integer justo arcu, tempor eu venenatis non, sagittis nec lacus.

Nullam ornare, sem in malesuada sagittis, quam sapien ornare massa, id pulvinar quam augue vel orci. Praesent leo orci, cursus ac malesuada et, sollicitudin eu erat. Pellentesque ornare mi vitae sem consequat ac bibendum neque adipiscing. Donec tellus nunc, tincidunt sed faucibus a, mattis eget purus. Read More

HADAS wins commendation at British Archaeology Awards by Tim Wilkins

Members will be pleased to hear that HADAS received a commendation at the prestigious British Archaeological Awards (BAA), for its latest publication “The Last Hendon Farm” The biennial BAAs, held in Birmingham on the 6th November 2006, are the most prestigious awards in British archaeology. Since their foundation in 1976, they have grown to encompass 12 awards covering all aspects of British archaeology.

HADAS was a finalist in the section for the Pitt-Rivers Award for the best project by a volunteer organisation. In presenting this category, the BAA said “We are delighted to report that we had an excellent set of submissions, sixteen entries in total. The overall quality of the work is the highest for many years and a tribute to the voluntary sector. We are particularly impressed where groups are training their own members to study and write their own reports”.

This last comment is especially relevant to HADAS, where the book is the first major product of the HADAS course on post-excavation analysis, run as a joint venture with Birkbeck College, University of London. Late breaking news: At the SCOLA (the Standing Committee on London Archaeology) archaeological awards ceremony on 14th November at the Society of Antiquaries at Burlington House, which looks at professional and amateur publications on London archaeology over the last two years, out of the seventeen entrants, HADAS’s “The Last Hendon Farm” was among the four finally short-listed. In the event, “Sutton House” a joint publication by English Heritage & the National Trust was deemed the winner and “Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate” by the Museum of London Archaeological Service (MoLAS) was second. The other short-listed book with HADAS’s was another MoLAS book “Old London Bridge”. The HADAS book was the only “amateur” publication among these illustrious professionals – quite an achievement!!

The book is excellently produced, with over 100 pages in total, containing 73 good quality photographs and diagrams, and gives much credit to those whose hard work have gone into the contributions and production. It illustrates much of the purpose behind the existence of local archaeological societies.

It is on sale for £11.99 plus £2.50 postage and packing within the UK and can be obtained from The Museum of London shop, London Wall, London EC2Y.

web: http://www.museumoflondonshop.co.uk/

email: shop@museumoflondon.org.uk or

telephone: 020 7814 5600.

Integer justo arcu, tempor eu venenatis non, sagittis nec lacus. Aenean sagittis, velit eget condimentum posuere, nulla massa consectetur nulla, iaculis lobortis sapien odio ac quam. Donec eu dui vel eros feugiat feugiat vel non lectus. Duis laoreet consequat diam in dictum. Mauris dui risus, sollicitudin id pretium a, ullamcorper non lacus. Read More

Our first lecture of 2004 was given by Nicole Weller, Portable Antiquities Liaison Officer and Community Archaeologist, who spoke about the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which arises from the 1996 Treasure Act.

Before the 1996 Act, the only formal framework relating to archaeological finds was the ancient common law of treasure trove, which was concerned only with objects made of precious metal and determining whether they should become Crown property. The foundation of the 1996 Act was the recognition that archaeological finds have a value other than that of any bullion they may contain, in the information they can provide, and that this information is worth collecting. The Act extended the definition of “treasure” to include items of high significance which were not previously covered, for instance two or more metal prehistoric objects, of any composition, found together now count as treasure, and, as before, there is a legal requirement to report the finding of treasure to the coroner to have its ownership determined.

Even under the extended definition, most interesting archaeological finds will not count as treasure, and to deal with these the Portable Antiquities Scheme was set up. This is a completely voluntary scheme set up to promote the recording of archaeological objects found by non- professionals of all sorts, especially metal detectorists, who in the past have had little contact with the archaeological community. It operates through a network of Finds Liaison Officers gradually built up since 1997, which now covers all the counties of England and Wales.

Nicole Weller is based at the Museum of London. She is happy to look at archaeological finds of all kinds, which she demonstrated by casting a professional eye over the multifarious small finds brought to the meeting by members of the Society, which added to the interest of the evening. Finds submitted to her under the PAS. will be identified, with the help of other staff at the Museum of London where necessary, and a written report provided. All items prior to 1650 are recorded on a database (with safeguards against unscrupulous interest) and will in due course be added to the Sites and Monuments Record. Some items prior to 1714 will also be recorded, and no one should be deterred from submitting finds because of doubts about their eligibility for recording – all are welcome. After examination, items will be returned to their finders, unless the objects are shown to be treasure, in which case fair compensation will be paid.

Although the scheme has only recently started to operate in our area, since it began in 1997 more than 150,000 finds have been recorded, so it can fairly be described as an established success. The good news: there is a nation-wide scheme gathering large amounts of information which would formerly have been lost, and locally we have an approachable and enthusiastic Finds Liaison Officer. And the possible bad news? Funding for the scheme is only guaranteed for three more years. Let us hope that by then its value will be as apparent to those who control the purse strings as it is to us.

Peter Nicholson

Victorian Philanthropist and Social Reformer. Talk by Micky Watkins