No. 591 JUNE 2020 Edited by Melvyn Dresner

The Annual General Meeting on Tuesday 9 June 2020 will not now take place due to the situation created by the coronavirus. At the present time we do not know when it will be possible to arrange another date. There will also be no Tuesday lectures until further notice. The monthly Newsletters should continue as usual. Keep well and safe until we meet again.

Layers of London Melvyn Dresner

Adam Corsini, of the Layers of London project https://www.layersoflondon.org/ gave a talk for HADAS on 10th March 2020, provided members with a practical session on how members can contribute and use this great resource. This website was funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, and brings together an amazing set of historic maps, and databases useful to anyone interested in the archaeology and history of London. You can add to data by contributing existing projects or can initiate your own. You can explore the map or the collections. The website allows users to overlay maps and data from different sources and periods, varying the order and fade. Datasets include the Archaeology of Greater London; London’s Archaeological Investigations 1972 – 2017 and Historic Environment Record.

Excavations at Clitterhouse Farm, Cricklewood by HADAS in 2019 (Part 8, Investigations beneath the café area in the north corner of the farm complex) Bill Bass and the Fieldwork Team

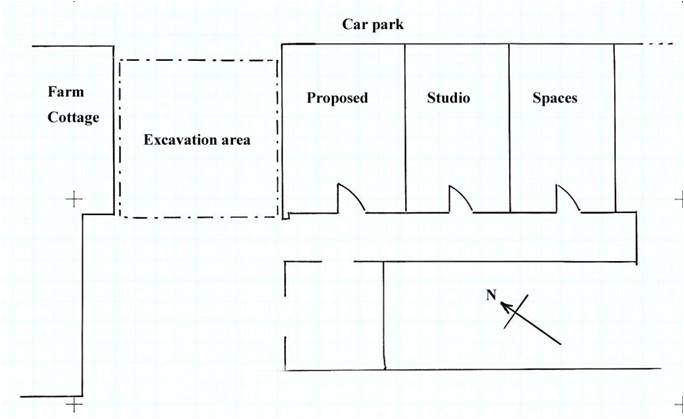

Clitterhouse Farm, Claremont Road, Cricklewood, NW2 1PH. Site code: CTH16, NGR: TQ 2368 8684, SMR: 081929, Site investigated August 2019. For background on this project please see HADAS Newsletters 539 (Feb 2016), 542 (May 2016), 543 (June 2016), 544 (July 2016), 556 (July 2017), 557 (Aug 2017) and 579 (June 2019).

Please also see other maps in HADAS Newsletters 542, 543 and 556 etc.

1

Introduction

Clitterhouse Farm, a moated manor site, has a long documentary history. Archaeological research work is being carried out to try and establish the Saxon/medieval and later layout of the site and the surrounding landscape use. Following on from previous the work here, the Clitterhouse Farm Project was demolishing their temporary café to be replaced with a purpose-built structure and building of new studio spaces in the northern range of the farm. HADAS was asked to carry-out initial archaeological investigations after the café was demolished. The temporary café was built between a gap in the northern range and the ‘Farm Cottage’, although the farm buildings have been rearranged over the years this is thought to be the original farm entrance which led into the moated area from the south-west, at least from the 17th century and probably earlier as seen on various maps, also see Newsletter 543 (June 2016). The 2019 dig began with site-watching of the removal of the substantial concrete slab which covered the area approximately 6m (E-W) x 5.60m (N-S), this was carried out by the groundwork contractor’s machine.

Excavation

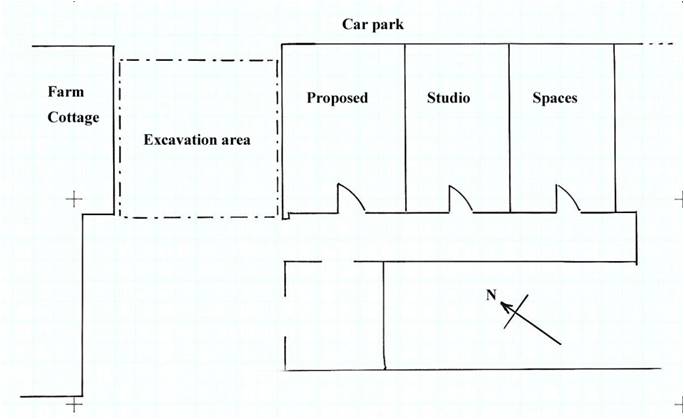

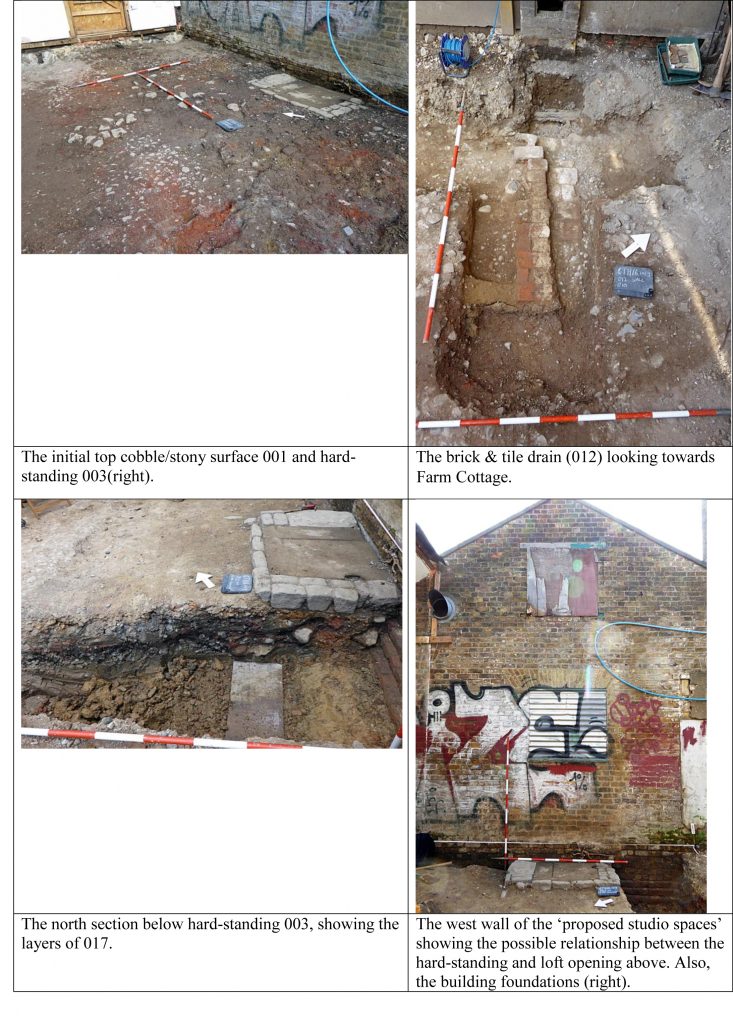

Some 15 members took part over the length of the dig, in sometimes very hot conditions, in fact the hottest week of the year. With the concrete removed the excavation started, beneath the concrete a sandy/gravel and cobbled surface began to emerge. This mixed layer (001) consisted of a sandy-silt with small to medium size pebbles and occasional larger ones, impressed into this were random large granite sett cobbles, with brick and tile scatters, some of this material was patchy, others were better sorted. The ordnance-level (OD) of this surface was 57.38m. Below (001) was (002) another patchy layer but with a better sorted pebble/cobble consistency in silty clay, about 0.08 – 0.14m in depth. Beneath this context a yellow-orange sandy layer (005) was uncovered which was relatively clean with occasional pebbles, this covered most of the excavation to a depth of 0.10 – 0.20m.

Not all features are shown for clarity.

Features seen beneath these upper layers but embedded in (005) include a rectangular shaped collection of large cobbles (granite setts?) surrounding two flagstones (context 003) arranged in rectangular shape 1.00m x 1.50m it was one course deep. This abutted the west end of the northern range wall. The unbonded cobbles and flagstones were reused,

2

they had slots and notches cut into them, but we are not sure about their use. Elsewhere on site we noticed concrete ‘door sills’, our cobble feature seems to have replaced one of these (had the previous sill been broken?), the truncated remains of which was could be seen in the wall, perhaps a more heavy-duty hard-standing of some kind was needed for hoisting materials to the loft hatch above.

Another feature excavated also surrounded by the sandy layer (005) and possible pebble surface layers was an east – west running brick and tile structure (012) on the east of the excavated area. The end-on bricks lined some flat tiles, this may have been the remains of a brick and tile drain, which was truncated by electric cable on the west side and by a modern sewer pipe through the central area. It is difficult to interpret due to the fragmentary remains, but we have seen a similar drain feature on a previous dig here but that was more substantial.

Two modern sewer drains crossed the site leading from a man-hole cover, it was decided to partially excavate the east-west branch of one of these to confirm this and to give an idea of the depth and nature of the section and deposits. The 0.50m wide cut was dug and the pipe was indeed found at 56.72 OD, adjacent to the north side were the remains of an earlier brick and tile drain. The sections at approximately 0.60m deep showed bands of smaller pebbles in a clay/sandy matrix.

On the western side of the excavated area adjacent to the ‘Farm Cottage’ we had a machine cut a slot of 4 x 1m, again to check the stratigraphy. Once again layers of pebbles, clay and sand sat on top of the natural London Clay at approximately 56.53 OD, Mike Hacker (pers comm.) comments – “I probed to c1.80m below the level of the cobbles. It was consistently moist, stiff, mid reddish-brown silty clay without inclusions. This is consistent with it being London Clay”.

Along the walls of both ‘Farm Cottage’ and the opposite northern range building, we noticed the construction ‘cuts’ (004) for the foundations of the structures. These were dug in various places to reveal a three-brick course ‘stepped’ foundation sitting on some gravel packing and the natural clay, this is a similar arrangement to what was found in the 2015 dig. A trench was dug immediately south of the cobble and flagstone hard-standing which gave us sections below this structure, a section in southern area of the site and a section of the northern range building foundation. Initially this was done by hand and later extended by machine. The sections showed varying bands, deposits and layers approximately 0.60m deep of gravel, pebbles, occasional lager cobbles, brick and tile deposits with bands of silty clay of various colours, all given one context (017). A silty black clay deposit approximately 0.10m thick runs through the central area of the section sloping from east to west. The section appears to show a continuous depositing action of dumping, tip-lines, levelling, infilling and repairing of the farm entranceway down to the natural clay level. We also reached the ground water-table level here as seen in the ‘moat’ trench in 2015.

Finds & Dating,

not all contexts are listed here is a selection.

Context (001)

Pottery: This upper layer beneath the concrete slab contained a variety of pottery, mostly smaller sherds including Refined Whiteware, REFW – (china), Transfer Printed Wares TPW, these have a general date of between 1800-1900. 8 English Porcelain sherds ENPO, have a wider date range of 1745-1900. There were 76 sherds of English Stonewares ENGS 1700-1900, mostly jars including a small ink jar, some of the sherds could be refitted, so some of the vessels were intact when deposited. Some samples of Post-medieval Redwares PMR 1580-1900 were found – mostly identified as flower pot.

Building Material: A selection of brick (whole or partial) were recorded, some glazed red tile, fragments of paving slab, peg and slate roof tile, mortar, sewer-pipe and other modern materials, were processed.

3

Stone: A possible worked flint interpreted as a blade was recorded as Small Find [005].

Animal bone: Four rib fragments showed evidence of gnawing and cut marks, some oyster shell fragments.

Metal/glass: An assortment of modern window and vessel glass fragments were recovered together with a variety of metal objects including nails, copper tubing, window latches and others.

Context (004) wall foundation cuts.

Pottery: 18 sherds of REFW including samples of dishes, cups and saucers, 4 sherds of a Yellow-ware plate 1820-1900 and minor amounts of ENPO, PMR and a sherd of Tin-glazed Ware C TGWC 1630-1846.

Other finds included 51 sherds of roof tile, some brick and a floor tile. An unusual find was a ‘lead weight’ domed in shaped, 118mm dia x 9mm depth, possibly a ‘greengrocer’s weight’ Small Find [001].

Context (005) sandy layer.

Pottery: Sherds of YELL, ENPO, TPW4 and REFW with part of a figurine foot (? lion). A ceramic bead, 11mm dia [small find 002]. 10 fragments of bottle glass including neck and rim sherds. Small samples of brick and slate.

Context (006) modern drain-pipe fill.

Context (012) brick and tile ‘drain’ feature

A complete brick sample was retained from this feature: possibly hand-made with no frog, it had possible organic tempering was red-purple in colour, possibly dating to 17th– 18th C. The drain and brick may date to before the current buildings and is similar to a drain seen in the 2015 excavations at the west end of the northern range.

Context (013) and (014)

Both these contexts were associated with the tile ‘drain’ (012) above, both, a brown sandy clay with pebbles. They contained similar pottery finds TPW, ENGS, REFW and SWSG Salt Glazed Stone Ware 1720-1780.

Of the Transfer Printed Wares a foot rim of a bowl had a Chinese style building design with the partial lettering ‘C&H HACKWOOD’. There were a number of potters of that name in operation in the potteries, of one these Hackwoods – “In 1856, the works passed into the hands of Cockson & Harding, who manufactured the same kind of goods, using the mark C & H, LATE HACKWOOD impressed on the bottom. Cockson retired in 1862” (http://www.thepotteries.org/mark/h/hackwood.html, accessed 17/3/20).

Fragments of a late 18th century ‘Mallet’ bottle were recorded as well as small amounts of peg/roof tile, nails and animal bone.

Context (017)

This mixture of contexts (see above) was deposited above the natural clay.

Pottery: Small sherd examples of PMR, ENGS – bottle, TPW- plate and saucer, CREA Creamware 1740-1830 plate and bowl and REFW – bowls.

Building materials: consisted of fragments of brick, pantile (roof), a substantial but incomplete floor tile and some drain pipe. An unusual find here was 2 sherds of co-joining Delft, blue on white decorated Wall Tile, with one corner design of part circle with the feet of two male figures, c 18th century, Small Find [006]. An amount of corroded metal ‘sheeting’ was found together with a hefty iron spike and nails.

Animal bone: fragments of rib, horn and a cattle-pubis were recorded together with some oyster-shell.

4

Other finds included minor amounts of bottle and mirror glass, and parts of shoe leather.

Interpretation

The earliest features would appear to be the remains of the two brick and tile ‘drains’. The first, just seen in the north section of the modern drain cut (007), the fragmentary remains of this feature was truncated and disturbed by its more modern replacement. The second (012) excavated in plan and at a higher level was again disturbed, a complete brick sample (described above) indicates this ‘drain’ was constructed of reused materials because the brick was worn and had 17th– 18th century features, but the layers it was dug into were of mainly 19th century in date. It’s possible the brick may be part of the demolition rubble from the nearby ‘wheat barn’ excavated in 2016 (HADAS Newsletter 556). As with a similar drain excavated elsewhere in 2015 this may be the remnants of the drainage system of the farm complex before “in the late 19th to early 20th century the main farm building is rebuilt in brick into a dairy farm.”

The other features were recorded – the granite cobble sett hard-standing, and the building foundations are described above. But for the most part much of the area was made-up of bands of pebble surfaces, cobbles, sand/clay deposits and dumps of brick and tile. All the layers had a mixture of finds dating to c1700-1900 and were all disturbed. These layers were excavated to a depth of 80cm and were sitting on top of the natural clay. Local geologist Mike Hacker commented in 2016 and it’s worth repeating “The well-rounded flint pebbles in the cobbled surface look as if they may well have come from the nearby deposits of Dollis Hill Gravel. One of the characteristics of DHG is that it is a poorly sorted mix of clay, silt, sand and pebbles. This makes it ideal for use as ‘hogging’ for roads and paths”.

Most of the finds were 18th – 20th century in nature (and later) with no sign of the earlier phases of the farm. It appears much of the area has been disturbed and truncated as part of the re-ordering history of the working farm and its buildings.

Acknowledgements:

Paulette Singer & The Clitterhouse Farm Project; HADAS Fieldwork Team (including site supervisors Andy Simpson, Melvyn Dresner and Roger Chapman); HADAS Post-Excavation Team; Gerald Gold & team, groundwork contractors; Mo – Tool Hire business owner and employees; and Mike Hacker – geologist.

HADAS Newsletter reports on Clitterhouse Farm investigations.

539: Part 1 – Introduction and Timeline.

542: Part 2 – The Excavations (2015).

543: Part 3 – Site Phasing and other things.

544: Part 4 – Report on the Animal Bone and Marine Molluscs and some small finds photos.

556: Part 5 – Investigations of the north corner of the farm complex (2016).

557: Part 6 – More information on a find (Char Dish) from Clitterhouse Farm.

579: Part 7 – History of Clitterhouse Farm, Hendon (lecture report).

During the dig, HADAS made a record of the standing buildings, a report on these findings will be published in a future newsletter.

5

6

What did you do in lockdown – another option? Don Cooper

For some time past, there has been a small hole in our lawn at the back of our house. Every time I fill it in the local fox (or some other animal) digs it out again. I wanted to know why the animal wanted to keep digging there and nowhere else in the garden.

So when that lovely spell of fine weather came along I determined to find out what was happening underground and being in lockdown and having little else to do I decided to do the project as a proper archaeological dig.

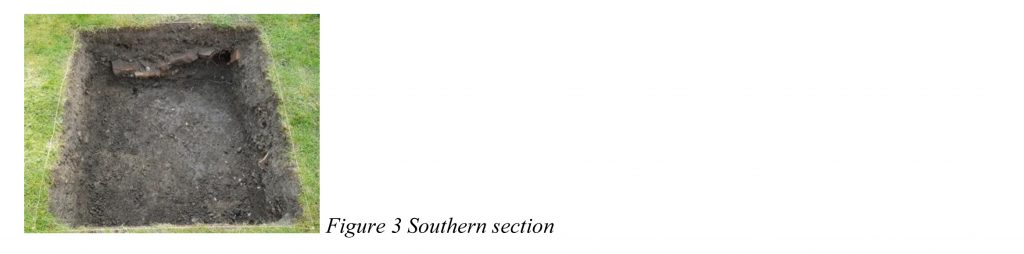

On Tuesday 14th April 2020 I marked out a 1m by 1m trench at TQ25866, 96442. I put down a tarpaulin for the spoil heap, oriented the trench north south, got the tools out including my trusty trowel and made a start de-turfing. By the end of the day I had made a good start on the trench as can be seen from the photo below.

On the next day I started bright and early at 10.30am. Digging down 20cm and turned up lots of finds of pottery, building material, clay pipe, window glass and animal bone. One totally surprising find was a hen’s egg with a green stamp! The egg was in a small hollow surrounded by leaves and twigs. I took the photo and left it on the spoil heap; it was gone next morning. How it got there and who deposited it, I haven’t the faintest idea. Most eggs as far as I know are stamped in red. It might explain why an animal kept digging out the hole.

By the end of day 2, I was down about 30cm all round. The southern section was showing a lot of building material in the form of brick, tile and sewer pipe.

On day 3, as I continued down, there were few finds and at just over 40cm down I came to the iniquitous London clay. I then dug a small sondage to be sure that I had reached natural.

On day 4, I decided to extend by 0.5m south to explore the building material tumble. I measured out the extension and deturfed. This was easy digging as there was a good deal of building rubble. Again, I dug down until I reached the London clay, which appears to be the natural.

On day 5, I backfilled the trench and restored the turf.

7

I spent day 6 washing the finds and recording them on an Excel spreadsheet. I disposed of much of the finds having recorded them. I photographed samples see below.

In summary, there were 101 sherds of pottery (many of them very small) weighting 449 grams. They consisted of post medieval redware (PMR) mostly flowerpot, refined earthenware (REFW), transfer-printed ware (TPW), and English stoneware (ENGS).

There were four sherds of clay pipe stems.

There were 63 sherds of glass mostly window glass (although there were 3 different thicknesses), but some bottle glass both green and white, as well as a sherd of a lovely scalloped bowl. The glass weighted 210 grams. There was a substantial amount of brick and tile.

There were a couple of animal bones and a small number of rusty nails.

My speculative conclusion is after looking at the deeds of the house, which was built in 1888, I think the builder’s rubble and hence the artefacts date from that period. I did not find anything earlier or anything that could not fit into that timescale.

8

The dig was a splendid experience. The weather was perfect, the ground reasonably soft after so much rain. I was outdoors and got lots of exercise and who cares if the lawn does not look great! I would recommend it to anyone!!

Æthelflæd, the Lady of the Mercians Dudley Miles

June marks the anniversary of Æthelflæd’s death; Dudley Miles tell her story 1150 years since her birth

Æthelflæd, who was the eldest child of King Alfred the Great of Wessex and his Mercian wife, Ealhswith, was born around 870, just before the Viking Great Heathen Army invaded England. By 878 they had conquered Northumbria, East Anglia and the eastern half of Mercia, but in that year Alfred won a crucial victory at the Battle of Edington. Ceolwulf, the last king of Mercia, is not recorded after 879, and he was succeeded as ruler by Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians. In the mid-880s he submitted to Alfred’s overlordship, uniting those Anglo-Saxons who were not under Viking rule. Alfred sealed the alliance by marrying Æthelflæd to Æthelred by 887. Æthelred was much older than Æthelflæd, and they had one known child, a daughter called Ælfwynn. Alfred’s eldest grandson, Æthelstan, who was to be the first king of England, was also brought up at the Mercian court.

Æthelred played an important role in defeating renewed Viking attacks in the 890s, together with Æthelflӕd’s brother, Edward the Elder, who became king on Alfred’s death in 899. Æthelred’s health probably declined sometime in the next decade, and Æthelflæd may have become de facto ruler of Mercia by 902. She re-founded Chester as a burh (fortified settlement) and probably enhanced its defences in 907, assisting the town to defeat a Viking attack. The archaeologist Simon Ward, who excavated an Anglo-Saxon site in the city, sees the later prosperity of the city as owing much to the planning of Æthelflӕd and Æthelred.

In 909 Edward sent a Wessex and Mercian force to raid the northern Danelaw. It seized the remains of the important royal Northumbrian saint, Oswald, from Bardney Abbey in Lincolnshire and brought them to St Peter’s Minster in Gloucester, which was renamed in his honour. Mercia had a long tradition of venerating royal saints, and this was enthusiastically supported by Æthelred and Æthelflæd. Anglo-Saxon rulers did not have capital cities, but the town became the main seat of their power and a centre of learning, at a time when western Mercia was the last stronghold of traditional Anglo-Saxon standards of scholarship.

9

The next year the northern Vikings retaliated for the attack on their territory with a raid on Mercia, but on their way back an English army caught them and inflicted a decisive defeat at the Battle of Tettenhall, which put an end to the threat from the northern Danelaw and opened the way for the recovery of the Danish Midlands and East Anglia over the next decade.

Æthelred died in 911, and Æthelflæd became sole ruler as Lady of the Mercians, although she had to give up the Mercian towns of London and Oxford to her brother. The accession of a female ruler was described by the historian Ian Walker as “one of the most unique events in early medieval history”. This would not have been possible in Wessex, where the status of women was low, but in Mercia it was much higher.

Edward and Æthelflӕd then embarked on the conquest of the southern Danelaw. Alfred had built a network of burhs (fortified boroughs) to strengthen the defences of Wessex, and his son and daughter constructed a string of new burhs to consolidate their defences and provide bases for attacks on the Vikings. She built forts at towns such as Bridgnorth and Tamworth, and repaired the Iron Age Eddisbury hillfort. Other towns she fortified included Stafford, Warwick, Chirbury and Runcorn. In 914, a Mercian army repelled a Viking invasion from Brittany.

In 917 three invasions from the Danelaw were defeated, and Æthelflӕd sent an army to capture Derby, which was the first of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw to fall. Her biographer Tim Clarkson, who describes her as “renowned as a competent war-leader”, regards this as her greatest triumph. However, she lost “four of her thegns who were dear to her”. At the end of the year the East Anglian Danes submitted to Edward, and in early 918 Leicester submitted to Æthelflӕd without a fight. The leading men of Danish ruled York offered to pledge their loyalty to her, probably for protection against Norse (Norwegian) raiders from Ireland, but she died on 12 June 918 before she could take up the offer. No such offer is known to have been made to Edward.

Æthelflӕd was succeeded as Lady of the Mercians by her daughter Ælfwynn, but in December 918 Edward deposed her and brought Mercia under his direct control. Æthelflӕd was buried next to her husband in St Oswald’s Minster in Gloucester.

The West Saxon version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle ignores Æthelflӕd’s achievements and just describes her as King Edward’s sister, probably for fear of encouraging Mercian separatism. But to the Mercians she was Lady of the Mercians, and Irish and Welsh annals refer to her as a queen. She has received more attention from historians than any other secular woman in Anglo-Saxon England. The twelfth-century chronicler, William of Malmesbury, described her as “a powerful accession to [Edward’s] party, the delight of his subjects, the dread of his enemies, a woman of enlarged soul”. The historian Pauline Stafford sees her as a “warrior queen”. “Like…Elizabeth I she became a wonder to later ages”.

The first biography of Æthelflӕd was published in 1993, but another five have been published in the twenty-first century, including a Ladybird Expert book by Tom Holland! By far the best is by Tim Clarkson. See also my article, ‘Æthelflӕd, Lady of the Mercians’, WikiJournal of Humanities, volume 1, issue 1, 2018, at https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Humanities/Æthelflæd,_Lady_of_the_Mercians.

During the C-19 crisis, HADAS would like to keep in touch with our members, through our social media and email, as well as through this newsletter and our C-19 News sheet provided by Jim Nelhams (thank you very much Jim!), if you want to be included, or assist with ideas to help run the Society during this difficult time. We welcome all contributions.

10

Obituary for John Heathfield Don Cooper with thanks to David Berguer

We are sad to report that John Heathfield, a long-time member of HADAS, died on Friday 27th March 2020 of coronavirus aged 91. John was born on 11th September 1928 and spent his working life in education first as a schoolteacher, then a headmaster and ending up as Inspector of Schools.

On his retirement, John started investigating the history of the local area and, in conjunction with his lifetime friend, Percy Reboul wrote a regular series of articles for the Barnet Times. They also wrote a number of books, either together or separately including “Around Whetstone & North Finchley”, “Barnet at War”, “Barnet Past & Present” “Days of Darkness” “Finchley & Whetstone Past” and “Teach Us This Day (All Saints School)”.

John was President of the Friern Barnet & District Local History Society and while president wrote “All over by Christmas” a 282-page book on what was happening on the Home Front in Barnet. Then in conjunction with David Berguer wrote “Whetstone Revealed” in 2016. I met John at Barnet Archives when they were briefly based in Daws Lane. He was researching away but had enough time to help me find what I was looking for. People with John’s amazing knowledge of the local area are few and far between. He will be sadly missed. RIP.

Obituary for Irene Gavorre Jim Nelhams

It was with some sadness that we heard of the death of Irene Gavorre on 21st February at her house in Edgware. Irene was a very private person. A non-driver, she did not attend our lectures but was always one of the first to register for our long trips away, up to and including our 2019 trip to Aberavon.

We bumped into her at the beginning of February on Edgware High Street. When she had not booked for our now cancelled trip to Stoke, we wrote to her house and received the news in response from a long-time friend of her daughter. Further information came from Sue Trackman.

“I knew Irene. She was a solicitor. She was clever, with a sharp wit who did not suffer fools. For a while (in the 1980/90s) we worked in adjoining offices in the legal department of the City of London Corporation and lunched together every day. Irene’s parents died young and she was brought up by an aunt. She brought up her daughter on her own. It was not an easy relationship but, after her daughter married an Israeli (and moved with him to Israel), matters improved and Irene had a good relationship with her granddaughter. Irene left the City Corporation in the 1990s to work in BT’s legal department and she remained with BT until she retired. We lost touch a few years after she left the City Corporation.”

11

OTHER SOCIETIES’AND INSTITUTIONS’ EVENTS

This section is temporarily cancelled due to the coronavirus outbreak.

************************************************************************

With many thanks to this month’s contributors:

Bill Bass, Jim Nelhams, Don Cooper and Dudley Miles

************************************************************************

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chairman Don Cooper 59, Potters Road, Barnet, Herts. EN5 5HS

(020 8440 4350) e-mail: chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary Jo Nelhams 61, Potters Road Barnet EN5 5HS

(020 8449 7076) e-mail: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer Roger Chapman 50, Summerlee Ave, London N2 9QP

(07855 304488) e-mail: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec. Stephen Brunning, Flat 22, Goodwin Court, 52 Church Hill Road,

East Barnet EN4 8FH1 (020 8440 8421)

e-mail: membership@hadas.org.uk

Web site: www.hadas.org.uk

______________________________________________________________________________

HADAS COMMITTEE

At the Annual General Meeting, which will be held on a date to be decided, Don Cooper is standing down as Chairman after many years of service, and Jo Nelhams as secretary is standing down as well, as is Sue Willetts. Please give some serious thought to how you can help the Society to function as it has done successfully for many years. At present, we have four committee meetings each year.

______________________________________________________________________________