______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

No. 619 OCTOBER 2022 Edited by Robin Densem

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

HADAS DIARY – Forthcoming lectures and events

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, until further notice lectures will be held online via ZOOM, all starting at 8 pm, although we do hope to get back to face-to-face lectures soon. As ever, our apologies to those who are unable to see online lectures. We will be sending out an invitation email with instructions about how to join on the day of each talk, so please keep an eye on your inbox.

Tuesday 11 October: Dr Martin Bridge (UCL): Tree-ring dating and what it tells us about the old Barnet Shop.

Tuesday 8th November : Nick Card: Building the Ness of Brodgar

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Some forthcoming lectures from other societies by Eric Morgan

Wednesday 12th October 2022, 2.30pm. Mill Hill Historical Society at Trinity Church, 100 The Broadway NW7 3TB. Sir Stanford Raffles in Mill Hill, by Dr Richard Bingle (The President of the Society). Please check at www.millhill-hs.org.uk

Friday 14th October, 7.00, Enfield Archaeological Society. A talk on Zoom 10,000 Years of Brentford – the Early History of a Riverside Town, by Jon Cotton (The Vice-President of the Society). The lectures page of the society’s website www.enfarchsoc.org says The link to access the lectures will be sent the day before to all members on our e-mail list and will also be published below (RD: I assume this would be on the lectures webpage)

Wednesday 26th October 2022, 7.45pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society at North Middlesex Golf Club, The Manor House, Friern Barnet Lane, London N20 0NL. London Underground by Barry Le Jeune. Please visit www.friern-barnethistory.org.uk & click on ‘programme’. Non-members £2 at the door.

Thursday 27th October, 7.30pm. Finchley Society at Avenue (Stephens) House), 17 East End Road, London N3 3QE. From Cinema to Film Star, a talk on the Story of The Phoenix in East Finchley by Rachel Kolsky (a London Guide). Non members £2 at the door. Also on Zoom, visit www.finchleysociety.org.uk to register for the link.

1

The House in the Woods and the Church at Hertingfordbury Robin Densem.

The site of the demolished 19th century Panshanger House and the Church of St Mary Hertingfordbury are near where I live in Hertford. My interest stems from living near both sites and by my family having had Stanley and Tilly

Cowper as long-term tenants, for perhaps 50 years, in the ground floor maisonette of our house in Balham, South

London. Stanley was always said to be a distant relative of a very rich family. Sadly I failed to ask him about his

family history before he passed away in 1983, a year or two after Tilly. I wish I had asked him. I think he was related

to the Cowper family that had built Panshanger House in Hertfordshire in the early nineteenth century. The Cowper

family worshipped in the nearby church of St Mary Hertingfordbury. The sixth Earl Cowper restored the church in

1845 and the seventh and last Earl Cowper carried out extensive works to the church in 1888-91 when it was also

richly furnished. The seven earls were buried at the church.

(B)

The Cowper family originated from London and Kent. Sir William Cower and his wife Sarah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Cowper were the parents of the first Earl Cowper who was raised to the newly

created earldom in 1718 by George I, as the first Earl Cowper. His mother Sarah wrote a diary and her history and

writing are described in a modern source thus: “In 1664, Sarah, the daughter of a London merchant, married Sir

William Cowper, a man above her social rank, whose landed estate was inadequate for his high status. Sir William

was one of many men who used government office, professional training, and mercantile marriage to obtain an estate and a seat in Parliament. “Never met two more Averse than we in Humour, Passions, and Affections; our Reason

and Sense, Religion or Morals agree not” quipped Sarah. Nor did she receive the respect due to her from her two

barrister sons, William and Spencer, who achieved spectacular success in the Whig political world. William

eventually became Lord Chancellor and an earl, while Spencer held high legal office. After producing her sons,

however, Sarah spent the rest of her life without leverage, financial security, or a compatible mate. She turned to her

diary to express her most intimate thoughts, and the political and religious views that developed from her reading.

An appendix of a hundred thirty-three books that she owned in 1701 is, in fact, a lengthy, but otherwise typical

reading list of a moderate Anglican woman.” (https://networks.h-net.org/node/16749/reviews/17765/whymankugler-errant-plagiary-life-and-writing-lady-sarah-cowper-1644 accessed 10/04/2022). Lady Sarah Cowper died in

1720, and her tomb stands outside St Mary’s Church, in the churchyard to the east of the chancel.

2

William Cowper (c. 1665 – 10 October 1723) pictured below in an 18th century portrait (Figure 2) was the first Earl Cowper from 1718 until his death in 1723. “Around 1704 the mansion house called Fitzjohns was pulled down and replaced by Cole Green House, a seven-bay mansion built for William Cowper, first Earl Cowper (first Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, 1707-10, again 1714-18; d(ied) at Cole Green 1723). He occupied the house in 1711 and settled there upon his retirement in 1718. Fruit and formal flower gardens lay close to the house, closely attended by the Countess. In 1719 the Earl bought the adjacent Panshanger estate. ”(https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000916?section=official-list-entry accessed 29.05.2022). His wife Mary kept a diary that has survived (https://www.hertsmemories.org.uk/content/category/herts-history/diaries-and-letters/hertfordshire-voices/the-diaries-of-lady-cowper accessed 3rd June 2022).

Fitzjohns and Cole Green House stood at Cole Green, near Panshanger in Hertfordshire, but on the opposite, south, side of the River Mimram. The Cowper family were well established in Hertfordshire and Kent, and William Cowper who was to become the first Earl Cowper was an English lawyer who threw his lot in with William of Orange when he landed in England in 1688. He became a Member of Parliament for Hertford and as a politician he moved in the highest circles at court and became the first Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain in 1707. George I created him first Earl Cowper in 1718.

Figure 3 above, shows an Image of Cole Green House in the 1790s, (HALS: DE/Of/3/496) (reproduced by kind permission of Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies, Hertfordshire County Council (HALS)).. Cole Green is about a mile west of the village of Hertingfordbury and the church of St Mary and the first Earl died at his Cole Green House in 1723 after catching a severe cold while travelling home from London. He was buried in the church where all seven Earls Cowper (1718-1905) were laid to rest. The second Earl, another William, left Cole Green House largely untouched but he commissioned Capability Brown to landscape its park In 1755. The second Earl died in 1764.

3

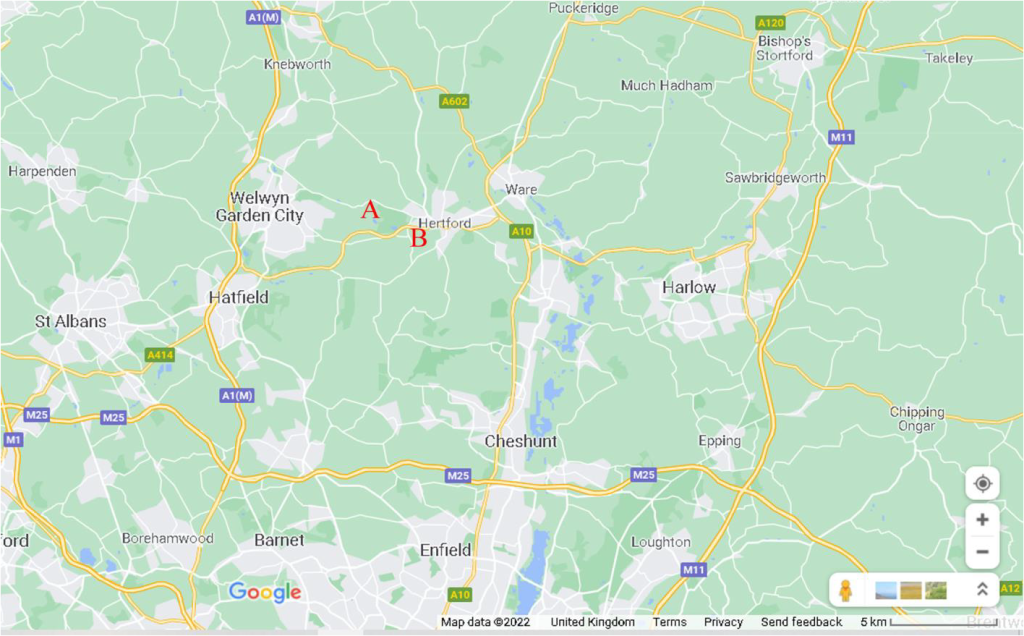

Figure 4: (above) The extract from Dury and Andrews Map of Hertfordshire of 1766 shows Cole Green House at the upper middle left, labelled ‘Earl Cowper’, just above the words ‘Cole Green Park’. The house stands at the north end of an avenue of trees within Cole Green Park. . The house lay at Cole Green, on the south-west side of the River Mimram, labelled ‘Maran River’. Panshanger House would be built on the north side of the river in the early nineteenth century in the Panshanger estate that the first Earl had purchased in 1719. In 1766, a set of buildings labelled ‘Panshanger Earl Cowper’ on the map stood there. The seven Earls Cowper were buried at St Mary’s Church, Hertingfordbury. The earldom was created for the first Earl in 1718, and the last earl died in 1905. The tower and nave of the church within its rectangular walled churchyard are shown, diagrammatically, in the Hertingfordbury village on the 1766 map extract. The church is shown, immediately to the left of the letter I of the word ‘HERTINGFORDBURY’ that runs in an arc left to right across the lower part of the map extract (Figure 4). The church is at the bottom right hand edge of the village. The town of Hertford, labelled Hartford is also shown to the east of the village on the Dury and Andrews map extract.

The second Earl’s son George Nassau Clavering-Cowper left England in January 1757 to undertake his Grand Tour of Europe. Styled Viscount Fordwich, he was 18 years old and heir to the earldom. All went well until the summer of 1759 when he arrived in Florence and fell passionately in love with a beautiful young Florentine lady. Hannah Gore.

Figure 5: The image above shows the Gore family in Florence, painted by Johann Zoffany in c. 1775 Charles Gore’s daughter, Hannah, is top left, Gore is centre and the aspiring groom, George Clavering-Cowper, Lord Fordwich, is the standing figure on the right. He married the sixteen-year-old Hannah Anne Gore on 2 June 1775. Their betrothal was commemorated with this painting that was commissioned by Fordwich’s new father-in-law. Fordwich declined to return home at the end of his tour, but instead headed back to Florence and was still living there when he succeeded his father to the earldom as the third Earl Cowper in 1764. By then he was thoroughly embedded in the cultural and social life of Florence and, apart from one short visit to England in 1786, he remained in Italy until his death in 1789 . Despite being Member of Parliament for Hertford from 1759-81, George lived in Italy, collecting fine art, and founded the famous Cowper art collection, that was later housed in Panshanger House. The image is from Wikipedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zoffany_Gore_Family.jpg accessed 20.05.2022).

On the death of George, the third Earl Cowper, in 1789, his eldest son, also named George (1776-1799), became the fourth Earl Cowper. The fourth Earl died unmarried in 1799. His brother, Peter (1778-1837), the second son of the fourth Earl, succeeded to the earldom as the fifth Earl in that year, (1799). Figure 6, above shows Earl Peter and is attributed to John Hoppner who died in 1810 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earl_Cowper , accessed 29th May 2022). Little happened with Cole Green Park until 1801-2 when Peter had Cole Green House demolished but he had set about landscaping the land at Panshanger, in line with Humphrey Repton’s proposals, doubtless with a view to providing a setting for the new house he intended to have built there, close to and probably incorporating the earlier house Panshanger House (C on Figure 7).

4

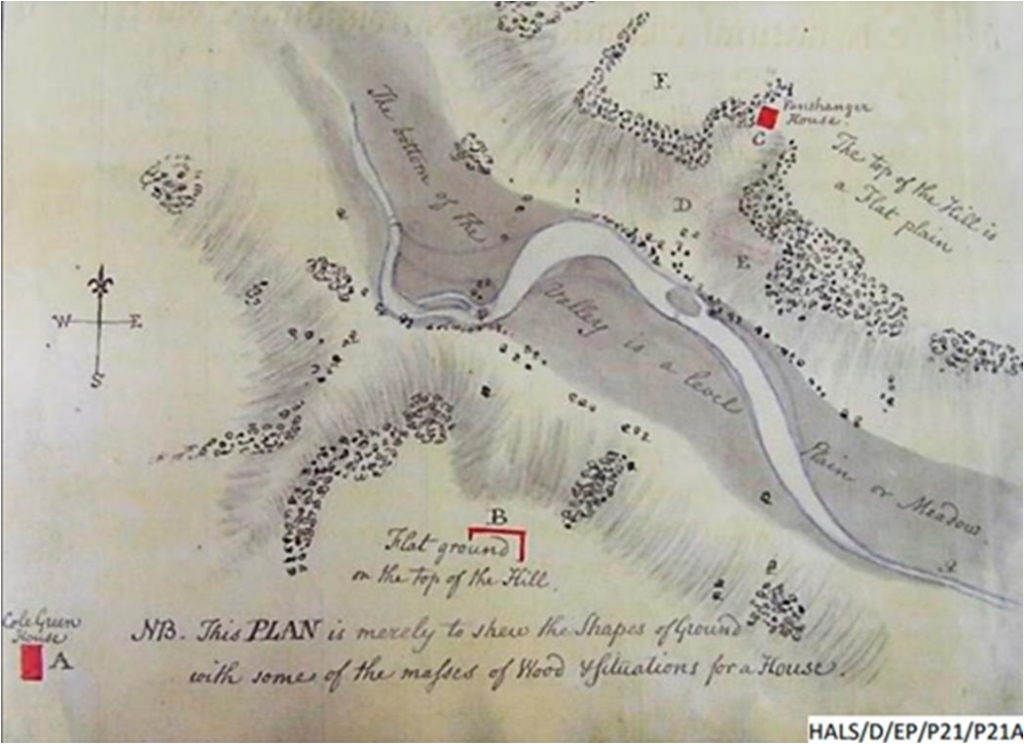

Figure 7 (HALS: DE/P/P21) is Humphrey Repton’s c. 1799 ‘Shape of Ground’ (Panshanger) from his ‘Red Book’ for Panshanger, showing landscaping proposals for Peter, the fifth Earl. The plan shows the location of Cole Green House at A and the site for the replacement house at Panshanger, at C. Repton seems to have taken little part in the implementation of his suggestions, which were instead and immediately supervised by Peter, the Fifth Earl. Planting began in 1799 and continued over several years. The plan is reproduced by kind permission of HALS. Deliberate landscaping works in the early 19th century were to widen the River Mimram to the south of the new Panshanger House, to form the ‘Broadwater’ to enhance the view and provide amenity.

The image above (Figure8 (HALS: DE/Of/3/496)) shows the old house at Panshanger as it was in the1790s and is reproduced by kind permission of HALS). Anne Rowe in her 2006 ‘History of the pleasure gardens at Panshanger’ researched for the Hertfordshire Gardens Trust explains that the image shows a house with at least two main building phases: the Elizabethan house on the right and the newer and grander extension on the left, perhaps dating from the first half of the 18th century .The buildings should be amongst the Panshanger buildings shown in the upper central part of the Dury and Andrews map extract (Figure 4) where they are labelled ‘Panshanger Earl Cowper’.

The early form of the new Panshanger House was built on the site of and perhaps around the old house in 1806-9 and the Fifth Earl occupied it in 1811 (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000916?section=official-listing . accessed 1st January 2022).

5

6

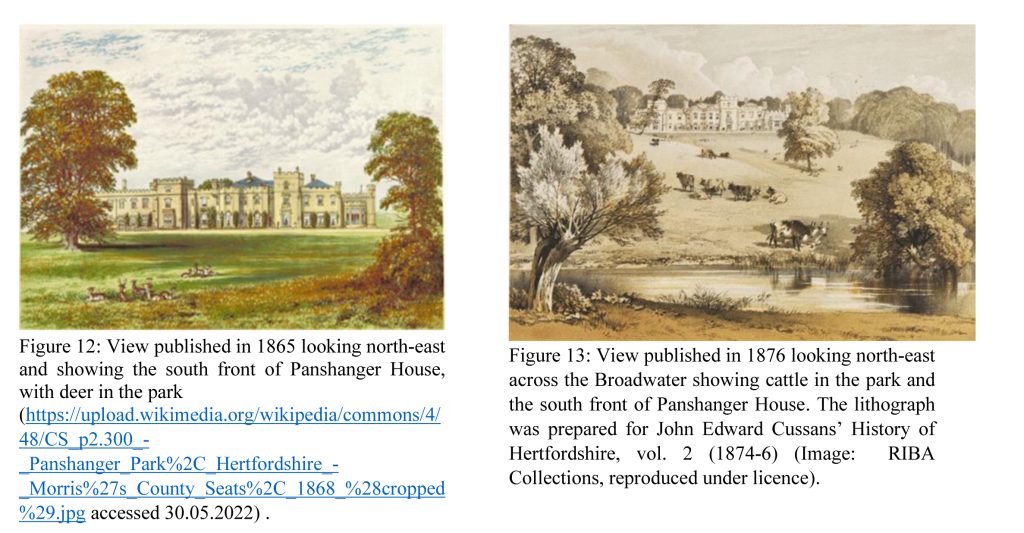

The design of the house was modified from Repton’s suggestions, first under the architect Samuel Wyatt and then, following his death in 1807, under another architect, William Atkinson who continued the work, building further additions and Gothicising the house . The site was carefully chosen to take advantage of the beautiful landscaped view south from the house .across the River Mimram, as shown in the recent below photograph .

Figure 9 above, is a recent photo by Paul Gallimore of Bedfordshire Walks https://bedfordshirewalks.co.uk/panshanger-park/ and included by his kind permission. The view is looking south-west and was taken from just south-west of the site of the early 19th century and now demolished Panshanger House. The site was carefully chosen to take advantage of the beautiful landscaped view south-west from the house .across the River Mimram, as shown in this recent photograph . The River Mimran can be seen in the centre of the photograph.

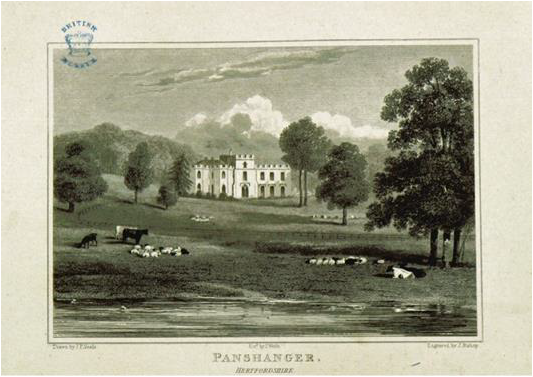

Figure 10 above, shows: An engraving of a drawing by J P Neale that was published in 1818. The view is looking north-east across the north bank of the ‘Broadwater’ (the widened River Mimran) and includes grazing cattle. The view shows an early extent of Panshanger House (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/42/Neale%281818%29_p2.142_Panshanger%2C_Hertfordshire.jpg accessed 2nd January 2022).

6

Figure 11 above, show s an Extract from Andrew Bryant’s map of Hertfordshire of 1822. The maps shows the park around the house in dark tone. The River Mimram is labelled ‘Maram or Memoram’ and the widened portion, the Broadwater, can be seen south-west of Panshanger House which is labelled simply as Panshanger. I have added a red circle to identify the Church of St Mary in Hertingfordbury (in the south-east corner of the map extract). The extract from the map(HALS reference CM140) is reproduced by kind permission of HALS.

7

After the death of Peter, the fifth Earl Cowper, in 1837 his wife Emily (nee Lamb) pictured above in Figure 14,

painted in 1803 when she was 16 years old in a Wikimedia Commons image (portrait of emily lamb – Google Search accessed 13th June 2022) continued to manage Panshanger until her death in 1867, having

remarried, to Lord Palmerston in 1839.

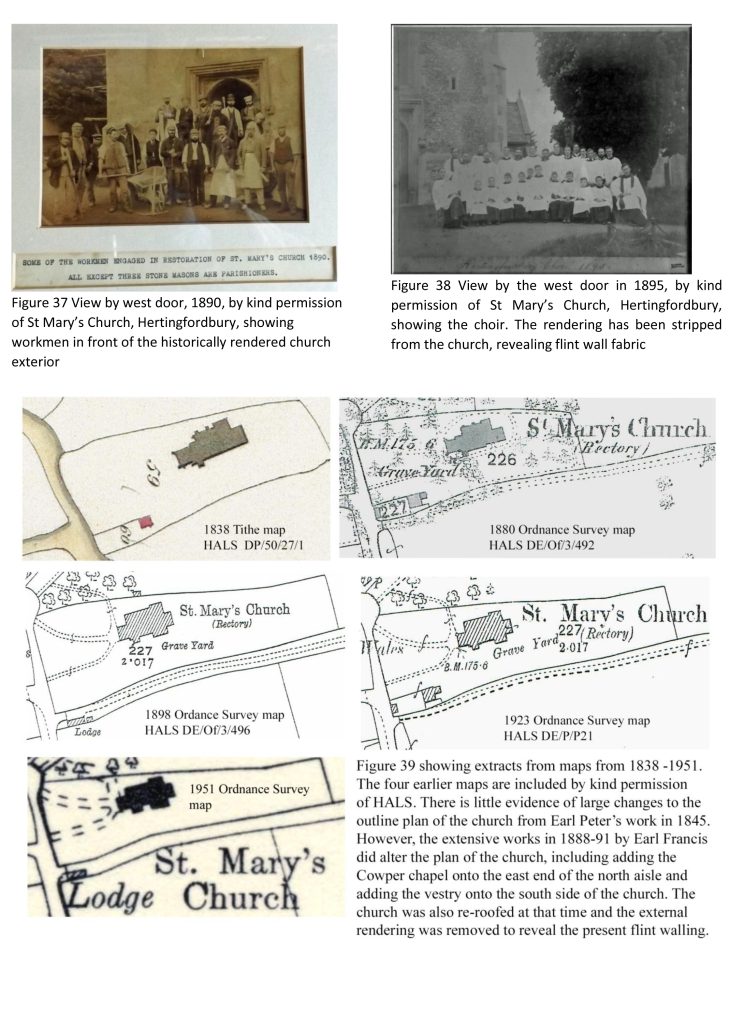

Earl Peter’s son George became the sixth Earl Cowper in in 1837 and he restored the Church of St Mary Hertingfordbury in 1845. On his death in 1856 his son Francis became the Seventh (and last) Earl Cowper. Important Cowper papers are held by HALS including material related to the Seventh Earl Cowper (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/22b66921-37fb-4e6d-beb7-5eb3235dd3a5) and may be

consulted at HALS by appointment.

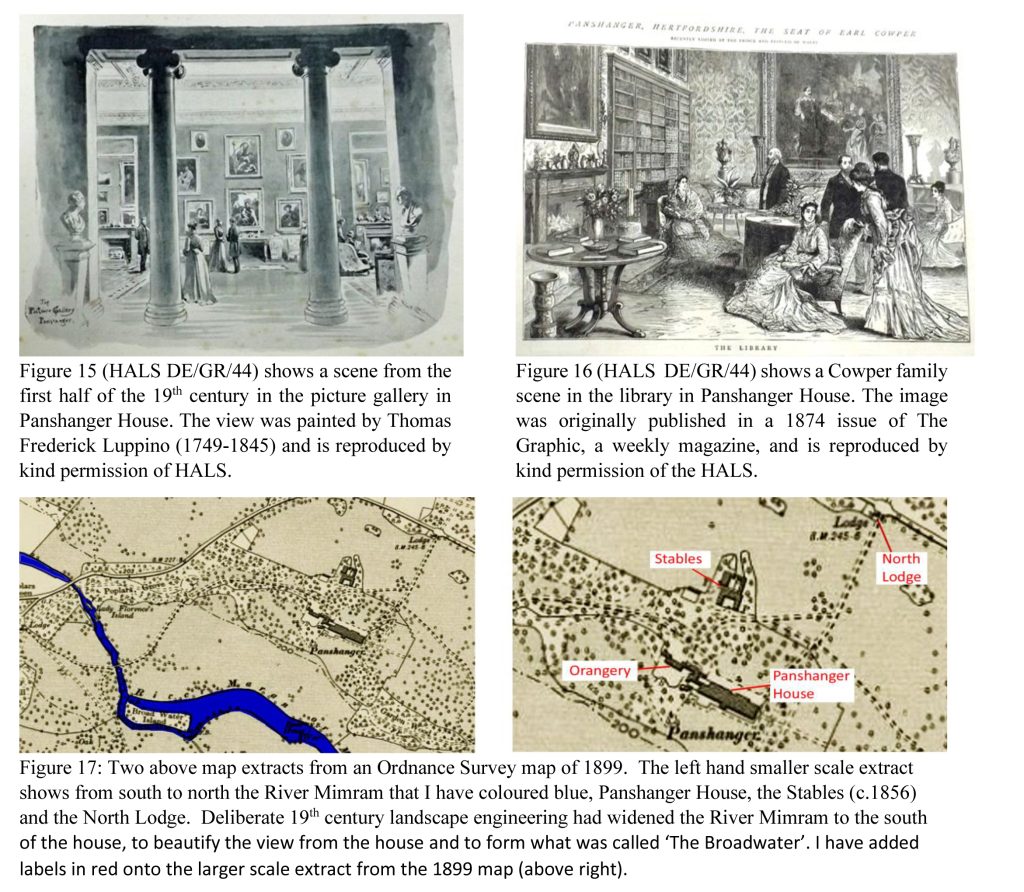

Panshanger House was richly furnished, and had a picture gallery displaying paintings including those collected by the third Earl in Italy in the later 18th century.

8

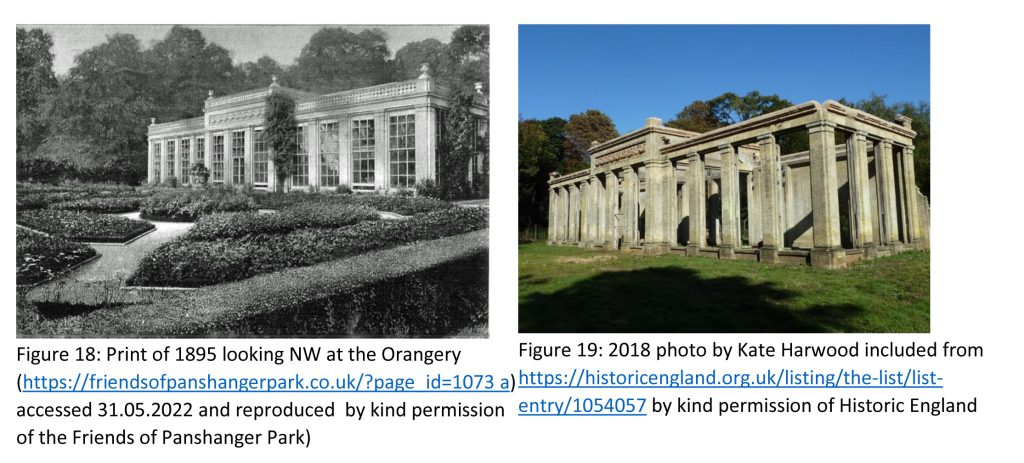

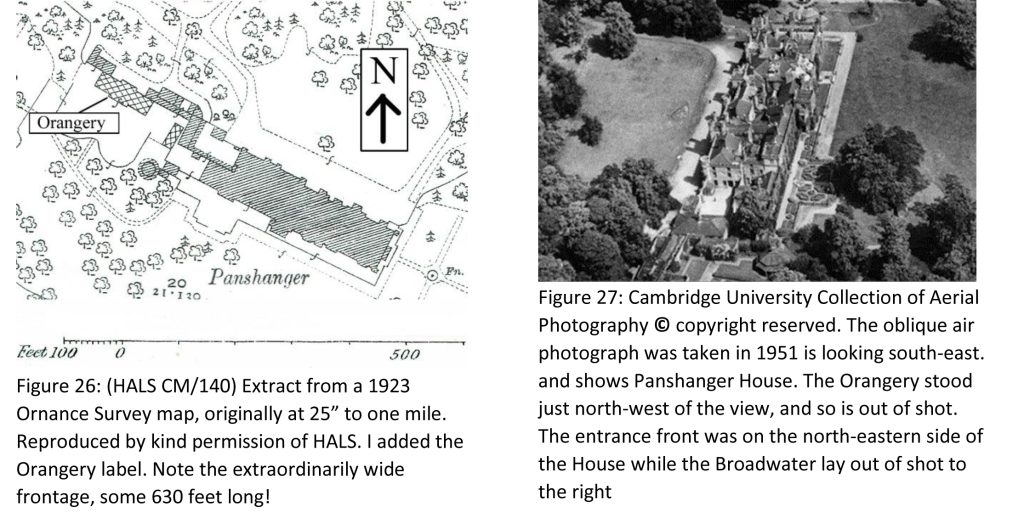

The Stables and the Orangery were added in c.1856 by Francis, the seventh Earl Cowper. The large and impressive south-facing Orangery of white brick with terracotta dressings in Classical style has lost its roof and windows but the main structure still stands. The brick-built stables (c 1856, now converted to office accommodation) stand north of the site of the house, surrounding a square stable yard on three sides. (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000916?section=official-list-entry, accessed 31.05.2022). Panshanger House was demolished in 1953-4 but its site can be visited and the adjacent Orangery still stands, though the impressive remains that survive have to be viewed through a protective by a wire mesh fence.

Francis was very wealthy and came to own more than one million pounds worth of assets which Sir Leo Chiozza Money, an analyst of the rich of the era, estimated was true of only eight British people who died “in an average year”. His probate was re-sworn in 1905 at £1.3 million, equivalent to about £145.6 million in 2020 (figures from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Cowper,_7th_Earl_Cowper accessed 31.05.2022).

Francis died in 1905 and his impressive tomb effigy is in the Cowper Chapel in the Church of St Mary Hertingfordbury beneath which he was buried, under the fine mortuary chapel he had built. He had funded the rebuilding of the church in 1888-91 including the construction of the integral chapel.

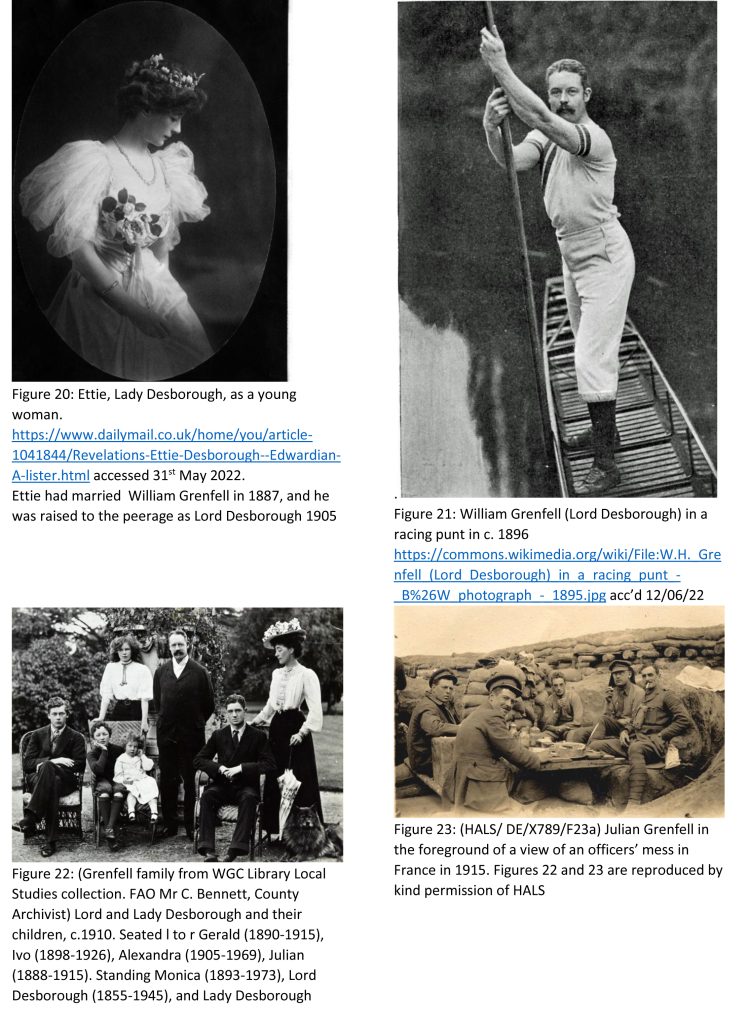

Despite a happy marriage Francis, the seventh Earl and his wife, Countess Katrine Cowper, had no children and his niece, Ettie Fane inherited Panshanger, together with other Cowper family estates in Hertfordshire, Kent and London, under the terms of the will of her uncle the seventh Earl Cowper who died at Panshanger in 1905. Katrine died in 1913 and her angelic-styled tomb memorial stands in the churchyard to the east of the church.

Ettie Fane Ethel (Ettie) Fane had been born in 1867 into an aristocratic family but she had no title. By the age of three she was an orphan when her father, Julian Fane died at the age of 42. She married William Grenfell in 1887.

She was a well-known hostess; Winston Churchill and H. G. Wells were amongst her guests, and she was said to be the confidante of six prime ministers (Rosebery, Balfour, Asquith, Baldwin, Chamberlain and Churchill). She and her husband were members of the social group known as “The Souls” which had been founded in 1885 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Souls, accessed 31 May 2022). Lord and Lady Desborough (he had been raised to the peerage in 1905) had three sons. Their eldest, Julian Grenfell, a war poet, was killed in the First World War in 1915 as was his brother William Grenfell later in the same year. Their third son, Ivo Grenfell, who became a farmer, died in a car accident in Kent in 1926. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ettie_Grenfell,_Baroness_Desborough, accessed 31.05.2022).

9

10

Panshanger house was richly furnished, as can be seen in the below image:

Figure 24: I took this photograph in December 2021 of an undated image mounted on a railed fence in

Panshanger Park. The fence encloses the site of the demolished house and the image illustrates the richness of a

reception room in Panshanger House.

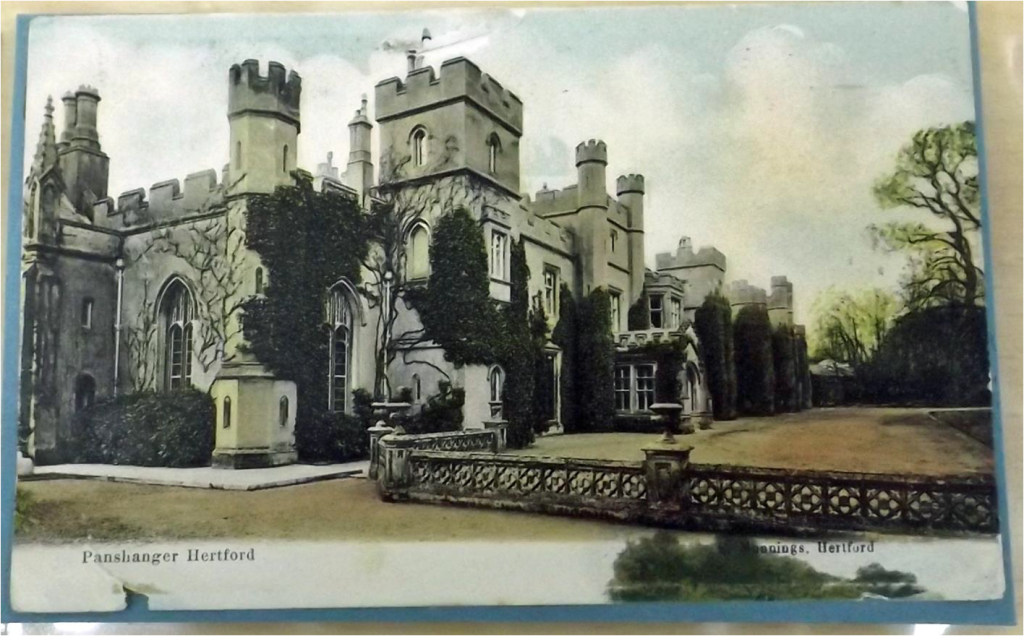

Figure 25: (HALS HBY 75(LSL) shows a view from a post-card of c.1910-15 looking east along the south-western face of Panshanger House.

11

Lord Desborough died at Panshanger in 1945 followed by Ettie, Lady Desborough in 1952. She had added more

bathrooms to the house and by time she died the house had some 90 rooms. https://www.ourhertfordandware.org.uk/content/places/hertingfordbury/panshanger-park/the-panshangerestate-

sale-1953/panshanger-house-sale-document accessed 9th January 2022

Ettie left Panshanger to her two daughters but as they didn’t wish to live in the house it was put up for sale in

1953 (https://www.ourhertfordandware.org.uk/content/places/hertingfordbury/panshanger-park/thepanshanger-

estate-sale-1953/panshanger-house-sale-document accessed 9th January 2022). Although attempts

were made to sell the house as an institution or school, there were no buyers after World War Two and the house

and 89 acres of land were sold to a demolition contractor and scrap dealer for £17,750 and the house was

demolished in 1953-4, and the building materials were sold in 1956.

Figure 28 (above): Author photo looking north-west in December 2021 across part of the site of the demolished Panshanger House, with standing remains of the conservatory in the background. The Orangery lies beyond and out of view.

12

Some parts of the former aristocratic park around the site of the former Panshanger House have been quarried for sand and gravel by Tarmac. Following restoration large areas of the park have been opened up as a country park and nature reserve. The Orangery and the site of Panshanger House can be walked to from a car park on Thieves Lane on the east side of the park. The walk is over a mile and is on gravel paths, or across grass. The Orangery and the site of the demolished Panshanger House are marked to the right of the symbol for a large tree in the upper central part of the below map (Figure 29) and can be visited, while the car park is shown by a red car symbol in the middle right of the image. The park is popular with visitors and dog-walkers, and has beautiful scenery and many interesting features including the River Mimram, lakes, wildlife and informative display panels.

Figure 29 above, shows a visitor’s plan of Panshanger Park (Your Visit | Panshanger Park (tarmac.com) accessed 4th January 2022) and included by kind permission of Tarmac and Maydencroft Limited.

In addition to walking through Panshanger Park to visit the site of Panshanger House and to admire the Orangery

and taking in the beauty of the location and the view of the Broadwater, one can visit the nearby and beautiful

Church of St Mary Hertingfordbury to which I will now turn.

13

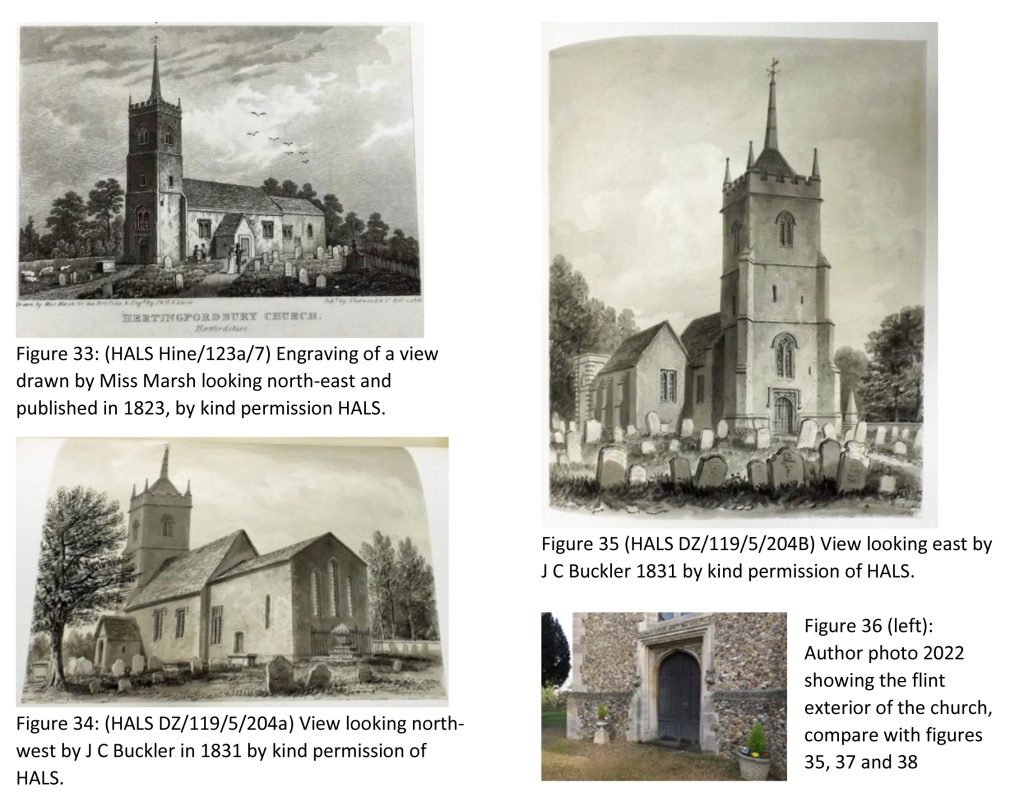

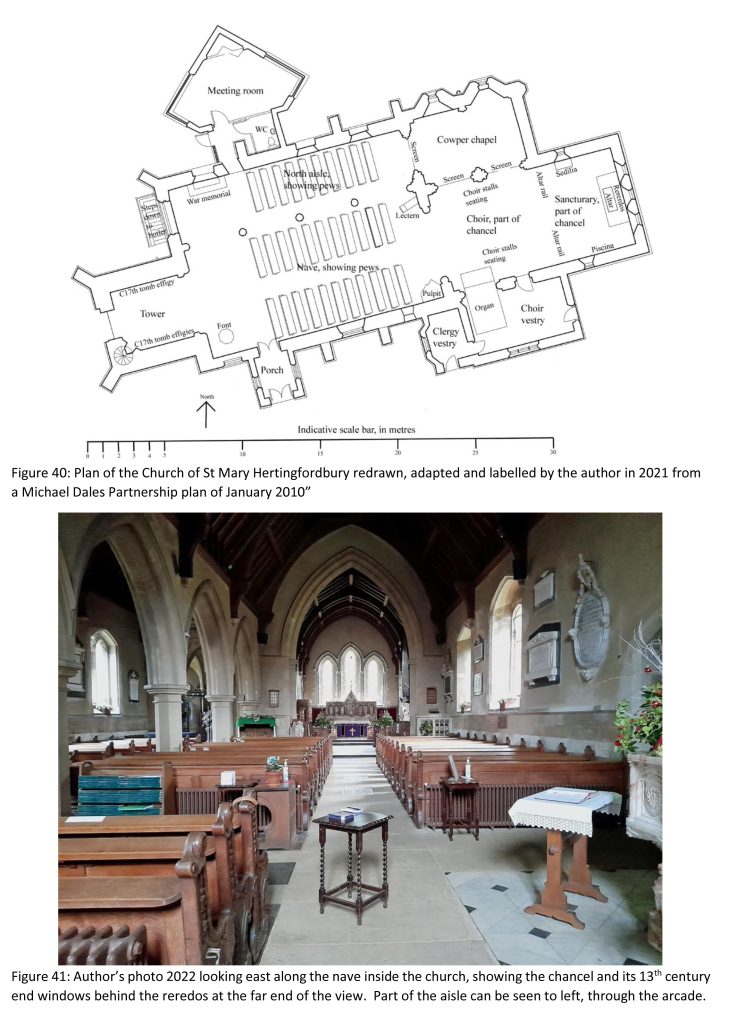

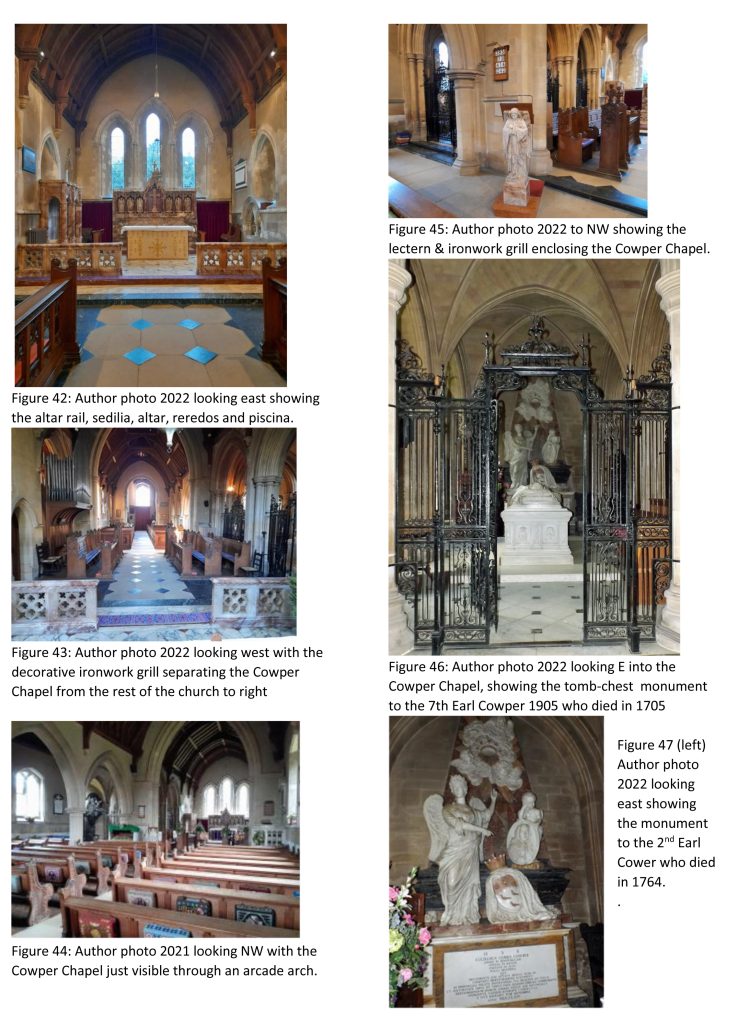

A church is mentioned at Hertingfordbury in the Domesday Book of 1086. The existing church was probably first built in the 13th century, perhaps on the orders of John of Gaunt and the first recorded rector was Richard de Wakering, 1329. The north aisle and west tower being added in the 15th century. (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/herts/vol3/pp462-468 accessed 01.06.2022). The church was restored in 1845 by the sixth Earl Cowper and was partially rebuilt in 1888-91 by the seventh Earl Cowper who added the Cowper Chapel.

Figure 32 above, shows the location of the church, circled red, in relation to the village of Hertingfordbury on an extract from an Ordnance Survey map of. The Watercress Beds mark the course of the River Mimram.

14

15

16

17

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the patient help kindly provided by Chris Bennett, County Archivist and for similar help also kindly provided by the staff at HALS. Others who helped a lot include the East Herts Church Recording Society; Paul Gallimore, Bedfordshire Walks; David Gorton, St Mary’s Church; staff of Hertfordshire Libraries Information; Jonathan Makepiece, British Architectural Library, RIBA; James Meek, HCUK Group; Ahad Noor, Information Services Office, Historic England; Jez Perkins, Estate Manager, Maydencroft Limited; Andrew Macnair; Professor Tom Spencer, University of Cambridge; and Tarmac.

What Have the Romans Ever Done for Us? Stewart Wild

Like most people I was aware that the Roman occupation of our part of Europe was generally ‘a good thing’.

The Romans left us with Mediterranean foodstuffs, new styles of clothing, an idea of architecture, Londinium and many other fine cities, a bridge or two, a wall or two, a degree of local government, theatres, markets and public baths, villas with lovely mosaics, amphitheatres, columns and triumphal arches, aqueducts, cisterns and reservoirs and, of course, straight roads. Not bad for beginners.

Canals in the Empire

What I hadn’t realised, however, is that their water technology also included canals. A canal of course is just a much larger form of aqueduct, but intended to carry boats and freight, and in some cases – drainage of marshland for instance – just to move large quantities of water elsewhere.

They go back a long way. The Romans learned a lot from the Egyptians; as early as 280BC the Canal of the Pharoahs connected the Mediterranean to the Red Sea via the Nile and the Great Bitter Lake, an overall distance of some sixty miles. In the first decade of the second century AD, under Emperor Trajan, this canal was restored and extended.

About the same time, a bridge and a canal (to circumvent rapids) were being constructed to facilitate trade routes and troop movements against local boss Decebalus in the Iron Gates region of the Danube in Dacia (present-day southwest Romania).

Some sixty years earlier, in Greece, Emperor Nero had supervised a particularly ambitious scheme to cut a canal across the isthmus on the route of the present-day Corinth Canal, but the plan was probably a bit too ambitious and abandoned after his death in 68AD.

Canals in England

After 120AD as the Romans began to consolidate their hold on this country under Emperor Hadrian, and while his famous Wall was being constructed up north, various water management schemes were initiated to try to drain the wetlands and fens of what we now call Cambridgeshire. This mainly consisted of cutting channels to join up existing river systems of the Cam, the Nene and the Ouse to assist drainage and land reclamation.

In south Lincolnshire, west of Spalding, there’s an unusual archaeological feature, only visible in cropmarks, known as the Bourne-Morton Canal. This runs straight for about four miles and some locals believe it dates from Roman times. It could have linked the area to a navigable river like the Welland providing a link to the North Sea at The Wash. There are a lot of dykes and drains in this part of Lincolnshire.

18

One particular Roman achievement hereabouts was the Foss Dyke, an eleven-mile navigational link now under the control of the Canal and River Trust. It connects the River Trent at Torksey to Brayford Pool on the River Witham in the county town of Lincoln and dates from about 120AD. It was restored a century later and ever since, at least until the 1970s, has been used to move all sorts of cargoes, including building stone, grain, coal and wood, to market. Nowadays it’s a valuable leisure route, popular with boaters and with a footpath and cycleway alongside.

Something else the Romans did for us.

A Little Dig Jim Nelhams

Entertaining our grand-daughters for a short time during their summer school holidays, we came across a little dig, complete with hypocaust.

Quite a surprise because we were at the time looking around Bekonscot Model Village in Beaconsfield (well worth a visit if you have not been there).

The village started in the late 1920s when Roland Callingham’s model railway outgrew his home and following an edict from his wife was moved to their back garden.

Many 1930s buildings were added, together with a tramway, a funicular railway, an airport and a harbour, but the extensive railway remains one of the highlights.

The cover of the guidebook contains the sentence “A little piece of history that is forever England”.

It’s good to know that archaeology has reached model villages.

19

❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖

With many thanks to this month’s contributors:

Robin Densem, Eric Morgan, Jim Nelhams and Stewart Wild

❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖

============================================================

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chairman Don Cooper 59, Potters Road, Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8440 4350),

e-mail: chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary Janet Mortimer 34 Cloister Road, Childs Hill, London NW2 2NP

(07449 978121), e-mail: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer Roger Chapmanr 50 Summerlee Ave, London N2 9QP (07855 304488),

e-mail: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec. Stephen Brunning 2 Goodwin Court, 52 Church Hill Road, East Barnet

EN4 8FH (0208 440 8421), e-mail: membership@hadas.org.uk

Website: www.hadas.org.uk