No. 631 OCTOBER 2023 Edited by Robin Densem

Avenue House Sunday morning working party meetings

The archaeology and heritage working sessions in the HADAS workroom at Avenue House are held on Sunday mornings, from 10.30am. The sessions are open to all HADAS members and are both important and convivial. I think it would be wise to check with the committee (committee-discuss@hadas.org.uk ) that the session will be held before you travel, as just occasionally a session is cancelled.

HADAS DIARY – Forthcoming lectures and events

We are pleased we are resuming lectures face-to-face following Covid, though lectures in winter may be on Zoom. Lectures are held in the Drawing Room, Avenue House, 17 East End Road, Finchley N3 3QE. 7.45 for 8pm. Tea/coffee available for purchase after each talk. (Cash please).

Tuesday 10th October 2023. Melvyn Dresner: Elsyng Palace – a digger’s view.

Tuesday 14th November 2023. Kris Lockyer (University College London): Mapping Verulamium.

A selection of other societies’ events – selected from information kindly provided by Eric Morgan

NOT ALL SOCIETIES OR ORGANISATIONS HAVE RETURNED TO PRE-COVID CONDITIONS. PLEASE CHECK WITH THEM BEFORE PLANNING TO ATTEND.

Wednesday 11th October, 2.30 pm. Mill Hill Historical Society/Trinity Church, 100 The Broadway, NW7 3TB. Talk on Grahame White and The London Aerodrome. By David Keen (Ex- RAF Museum). Please visit www.millhill-hs.org.uk

Tuesday 24th October, 1-2 pm. London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, EC1R 0HB. A Day in a London Life 1623. Talk. Also on Zoom. Free. Booking Essential. On Shakespeare’s Achievements making him one of Jacobean London’s most famous sons. But what was life everyday like for him and his contemporaries? Please visit London Metropolitan Archives – City of London.

Sunday 5th November, 2.30 pm. Heath and Hampstead Society., Laughter in Landscape. Meet at Old Bull and Bush, North End Way, NW3 7HE. Guided Walk led by Lester Hillman (Tour Guide) About Comedy, Humour in Science, Film, Music, Local Links to Actors, Writers, Theatre and The Landscape. Lasts approx. 2 hours. Donation £5. Please contact Thomas Radice on 07941 528034 or email hhs.walks@gmail.com or visit The Heath & Hampstead Society – Fighting to preserve the wild and natural state of the Heath (heathandhampstead.org.uk)

Tuesday 7th November, 6 pm. Gresham College, Barnard’s Inn Hall, Holborn EC1N 2HH. Pilgrimages, Pandemics and The Past. Talk by Tom Holland. Also on line. Ticket Required. Register at www.gresham.ac.uk. Please see Pilgrimages, Pandemics and the Past | Gresham College. FREE. Joint with Royal Historical Society. Will explore how tracing ancient routes on foot and experiencing travel as people did in age before trains and cars can offer insights into the past. Will also draw on experience of reading Chaucer and undertaking pilgrimage during and after the pandemic.

Wednesday 8th November, 2.30 pm. Mill Hill Historical Society. (address as 11th October) History of Highgate Cemetery. Simon Edwards.

Wednesday 8th November, 6 pm. Gresham College, Were there Pagan Goddesses in Christian Europe? Talk by Ronald Hutton, view on line. Please see www.gresham.ac.uk/whats-on/pagan-goddesses Free. Considers a set of superhuman female figures found in Medieval and early modern European cultures. Mother nature the roving nocturnal lady often called Herodias, The British Fairy Queen and the Gaelic Calleach.

1

Wednesday 8th November, 8 pm Hornsey Historical Society. Talk on Zoom, Charles Roach Smith by Dr Michael Rhodes. Please visit www.hornseyhistorical.org.uk for further details.

Friday 10th November, 7.30 pm Enfield Archaeological Society – Jubilee Hall, 2 Parsonage Lane/Jnc Chase side, Enfield EN2 0AJ Towards a Geoarchaeology of London. Talk by Jason Stewart. Please visit www.enfacrchsoc.org for further details.

Monday 13th November, 3 pm Barnet Museum and Local History Society. St John Baptist Church, Chipping Barnet, CNR High Street/Wood Street, EN5 4BW. David Livingstone and Hadley Green – Out of Africa. Talk by John Hall.

Thursday 16th November, 8 pm. Historical Association – Hampstead and NW London Branch. Fellowship House, 136A, Willifield Way, NW11 6YD (off Finchley Road, Temple Fortune). 1942 Britain at the Brink. Talk by Taylor Downing. Argues that Britain’s darkest hour was 1942 when British people faced the prospect of defeat, when a string of Military disasters engulfed Britain in rapid succession. Also shows how unpopular Churchill became, using mass observation archive new material. Hopefully also on zoom, please email Gulse Koca (Chair) on kocagulse@gmail.com or telephone 07453 283090 for details of zoom link and how to pay (There may be a voluntary charge of £5) Refreshments afterwards. Please note change of chair. These details also apply on the talk on 19th October, shown in the Hadas September Newsletter.

Friday 17th November, 7.30. pm Wembley History Society. St Andrew’s Church Hall (behind St. Andrew’s new church) Church Lane, Kingsbury NW9 Bombed Churches of the City of London. Talk by Signe Hoffos.

Saturday 18th November, 10.30 am – 6 pm. Lamas Local History Conference. Museum of London Docklands, West India Quay, off Hertsmere road, E4 4AL. The London Menagerie – Animals in London History. Tickets are £15 (£17.50 after 1st November or £20 on the day, subject to availability) For more info, including the full programme and to book, please visit www.lamas.org.uk/conferences/20.local-history.html.

Wednesday 22nd November, 7.45 pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society. North Middx Golf Club, The Manor House, Friern Barnet Lane, N20 0NL. London’s Parks and Gardens. Talk by Diane Burstein (Tour Guide) Please visit www.friernbarnethistory.org.uk and click on programme or phone 0208 368 8314 for up to date details (David Berguer, Chair) Non-member £2. Bar available.

Saturday 25th November, 10 am – 4 pm. Amateur Geological Society North London Mineral Gem and Fossil Show. Trinity Church, 15 Nether Street, N12 7NN (Nr North Finchley Arts Depot, Near the Tally Ho Pub) Large Hall with Jewellery, Gems. Fossils, Rocks, Minerals, Books, Maps and refreshments. Admission £2. For details visit www.amgeosoc.wordpress.com.

Thursday 30th November, 7.15 pm. Finchley Society. Drawing Room, Avenue (Stephen’s) House, 17 East End Road, London N3 3QE. Quiz Supper with Andy Savage as Question Master. For further details please visit www.finchleysociety.org.uk.

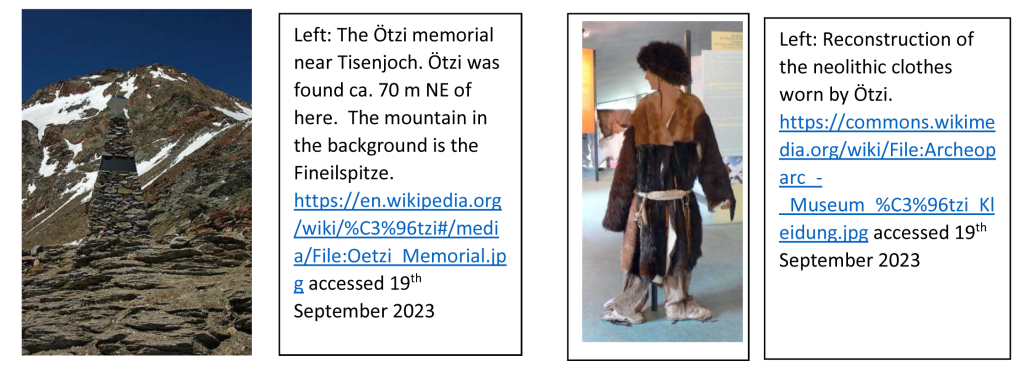

Iceman Otzi is not the rugged warrior we had believed Stewart Wild

OTZI the Iceman was probably bald with dark skin – not too dissimilar to his desiccated state, scientists have said. The natural mummy, which dates from 5,300 years ago, was found in the Ötztal Alps at the border with Austria and Italy in September 1991, and is Europe’s oldest mummified human.

The current reconstruction of Otzi in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano suggests that he had light eyes, a shaggy head of hair, a beard and the lightish skin of an Alpine climate. But genetic analysis suggests he had a predisposition for male pattern baldness, with dark eyes and dark skin.

“It was previously thought that the mummy’s skin had darkened during its preservation in the ice, but presumably what we see now is actually Otzi’s original skin colour,” said Albert Zink, the study co-author.

2

Prof Johannes Krause, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Germany, added: “The

genome analysis revealed phenotypic traits such as high skin pigmentation, dark eye colour and male pattern baldness. It is remarkable how the reconstruction is biased by our own preconception of a Stone Age human.”

The new analysis, published in the journal Cell Genomics, also changes Otzi’s ancestry. Genetic profiling

in 2012 suggested that he had descended from a mix of native hunter-gatherers, migrating farmers from

Anatolia and Steppe herders. But the new results find no link to the Steppe herders, with scientists

discovering that modern DNA had accidentally become mixed up with the original samples.

(SOURCE: The Daily Telegraph, 17 August 2023, item edited by Stewart Wild).

Reconstruction of Ötzi mummy as shown in Prehistory Museum of Quinson, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence,

France (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otzi-Quinson.jpg accessed 19th September 2023)

3

HADAS Open Day Jim Nelhams

As advertised in previous newsletters, HADAS held an Open Day at Avenue House on Saturday 16th September.

Considerable thought and planning had gone into this event, spearheaded by Bill Bass and other members of the Sunday Morning group, with assistance from members of the Avenue House staff.

The Stephens Museum near the café was opened up for our use, and display boards, which attracted much interest, showed part of our history, including our digs. Also in the museum were some activities for children courtesy of Janet Mortimer, Sue Loveday and Sue Willetts. The tables were occupied for large parts of the day by interested children and their parents. Outside, children could also get their face painted for a small charge.

Visitors during the day included Martin Russell, His Majesty’s Deputy Lieutenant of Greater London and the Lord-Lieutenant’s Representative for Barnet, and Barnet Councillor Philip Cohen, the council nominee to the Council for British Archaeology. We signed up five new members including Councillor Cohen.

Out in the grounds, on the area of the old pond (now no longer), Don Cooper led a team demonstrating the use of our resistivity equipment.

4

We were also joined by members of the Finchley Society and Barnet Medieval Festival, both groups having tables of displays.

Reaction from members of the public was very positive, with some expressing surprise that, apart from the face painting, there were no charges.

Photos: Melvyn Dresner/Andy Simpson.

5

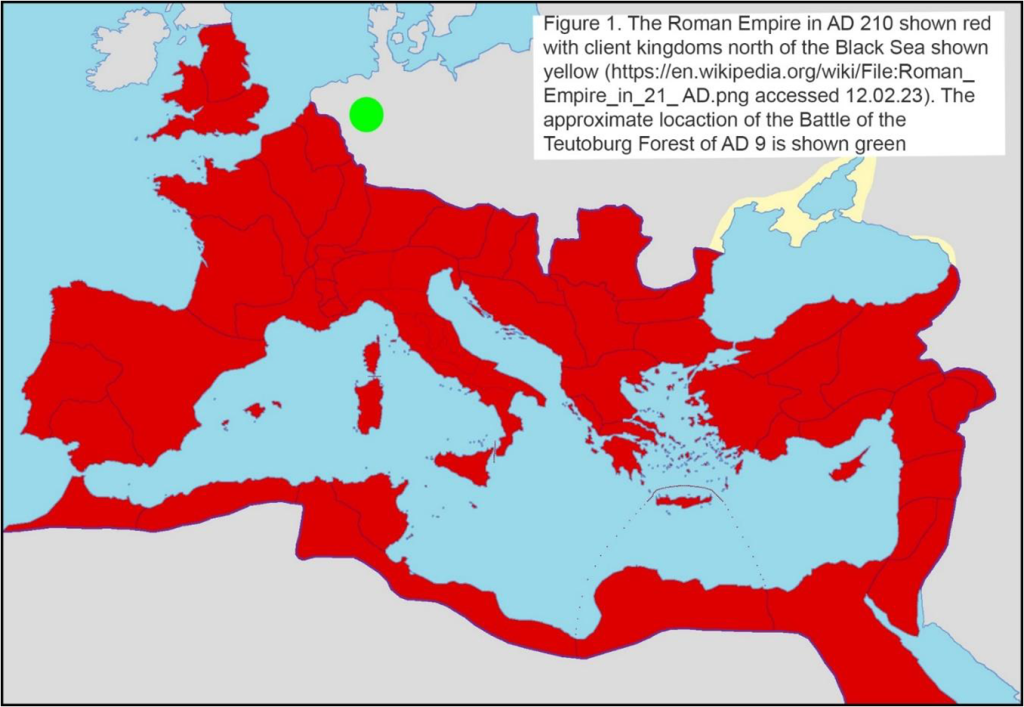

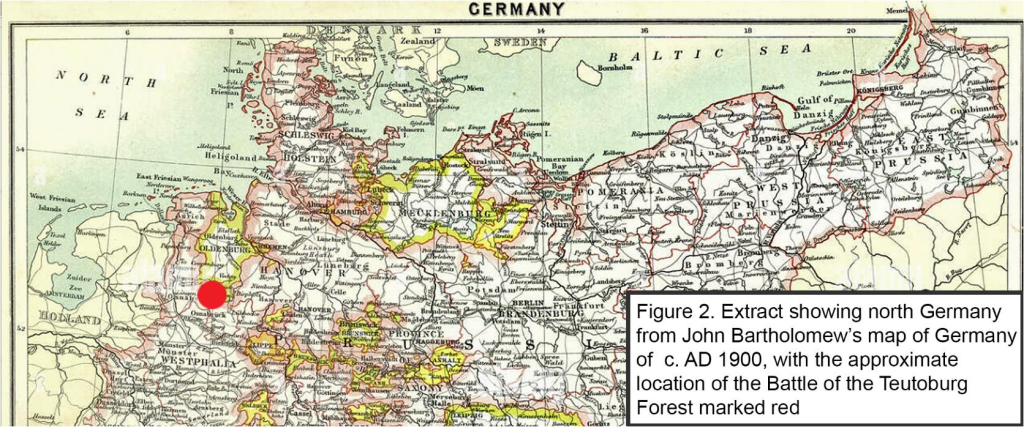

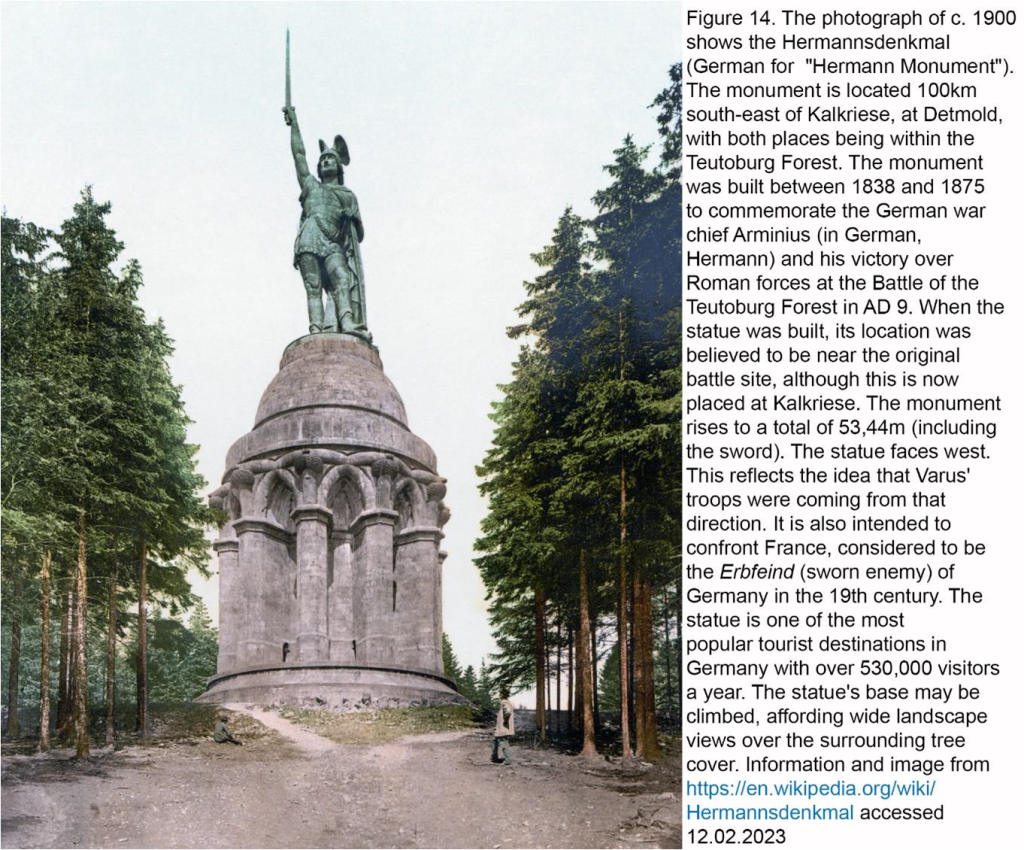

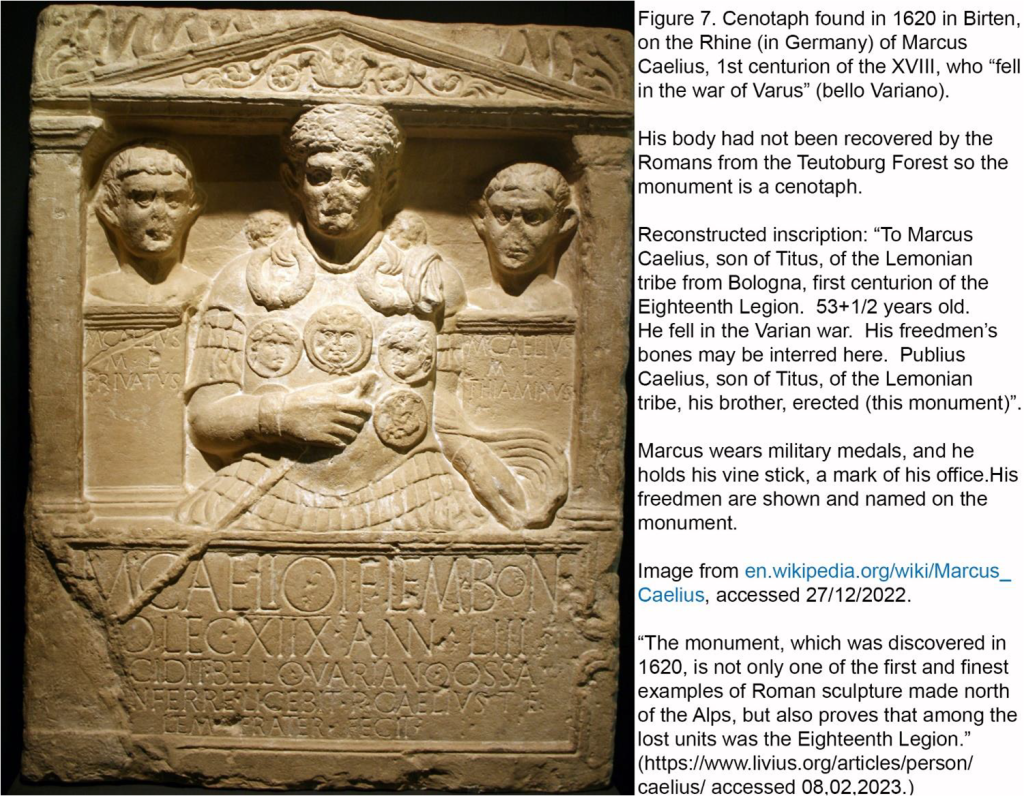

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest AD9: The massacre of a Roman army Robin Densem

Introduction

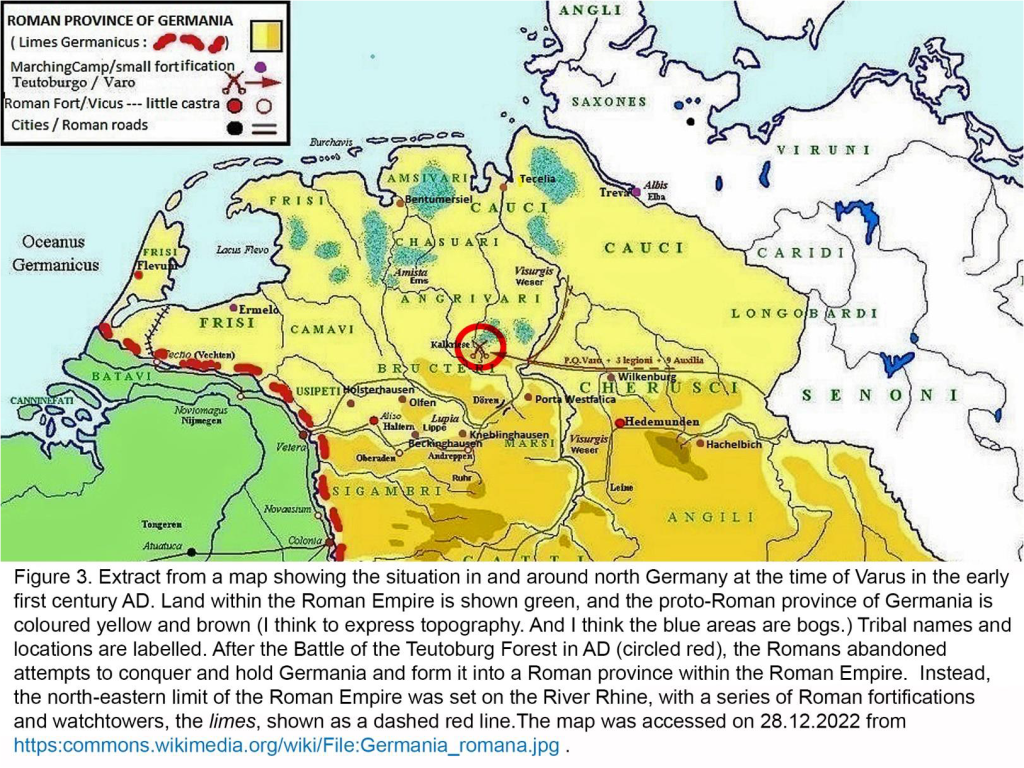

Following centuries as a republic, Rome and its dominions was ruled as an empire by the adopted son of Julius Caesar, Augustus, as its first emperor, from 27 BC to his death in AD 14. After a Roman defeat of the banks of the River Rhine in 16 BC when the Roman governor of Gaul, Marcus Lollius, was defeated by a German raiding party which captured a legionary standard, Augustus turned his attention to the evidently dangerous north. Not satisfied with the Rhine as a frontier, he decided to advance into Germany to move the frontier 800km north-eastwards from the Rhine to the River Elbe.

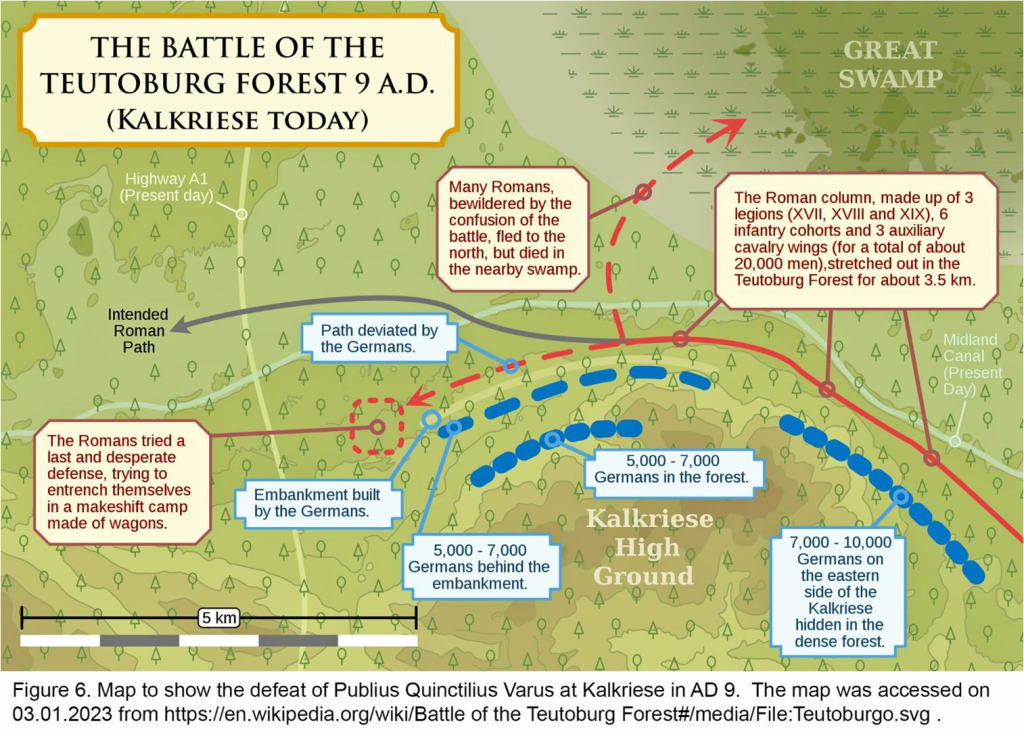

Ancient sources tell us about the Roman attempts to conquer Germany and about the three or four day long battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9 when the Germans massacred a Roman army of three legions and nine auxiliary units, a force of perhaps 20,000 men, or more, led by Publius Quinctilius Varus (Varus). Augustus was so distraught after the loss of the three legions that the Roman writer Suetonius says Augustus often wailed, “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!” Augustus had had a total of around 30 legions, each of about 5,000 men, accompanied by auxiliary units of 500 and others of 1,000 men which doubled the total size of his forces. The armies of auxiliaries and legionaries were to defend the Roman empire and to conduct offensive operations, so the loss of three legions and nine auxiliary units was a disaster considering the extent of the Roman empire and the length of its borders. After the battle, called by the Roman the Clades Variana, the Varian Disaster, the Augustus abandoned attempts to conquer Germany. Adrian Murdoch’s 2008 title for his book ‘Rome’s Greatest Defeat: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest’ gives a flavour of a modern, perhaps overstated, view of the very serious extent of the Roman disaster. (It could be argued that Hannibal’s victory of the Romans in 216 BC at the battle of Cannae was a greater defeat for the Romans who lost more men then.)

Ancient Latin sources for the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest include the Roman History, written by Velleius Paterculus who lived c. 19 BC – c. AD 31; Strabo’s Geography that he wrote in c. AD 20; Tacitus’s Annals (c. AD 120); and Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars (c. AD 121). Dio Cassius was a later writer who wrote his Roman History in Greek in the years AD 211-233. None of the ancient sources are exactly contemporaneous with the battle, and all relied on earlier sources, including official records. Excitingly, archaeology has revealed the actual battle site and many artifacts, and offers a correlation, confirmation and amplification of the account from the well-known ancient written sources.

6

The text below on the historical background and description of the battle is from Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_campaigns_in_Germania_(12_BC_%E2%80%93_AD_16)#Campaigns_of_Tiberius,_Ahenobarbus_and_Vinicius accessed 7th January 2023.

Campaigns before the Clades Variana (the Varian Disaster): Campaigns of Drusus (the elder, 36 BC – 9 BC)

Nero Claudius Drusus (Drusus the Elder), an experienced general and stepson of Augustus, was made governor of Gaul in 13 BC. The following year saw an uprising in Gaul – a response to the Roman census and taxation policy set in place by Augustus. For most of the following year he conducted reconnaissance and dealt with supply and communications. He also had several forts built along the Rhine, including Argentoratum (Strasburg, France), Moguntiacum (Mainz, Germany), and Castra Vetera (Xanten, Germany).

Drusus first saw action following an incursion by the Sicambri and the Usipetes from Germany into Gaul, which he repelled before launching a retaliatory attack across the Rhine. This marked the beginning of Rome’s 28 years of campaigns across the lower Rhine.

He crossed the Rhine with his army and invaded the land of the Usipetes. He then marched north against the Sicambri and pillaged their lands. Travelling down the Rhine and landing in what is now the Netherlands, he conquered the Frisians, who thereafter served in his army as allies. Then, he attacked the Chauci, who lived in northwestern Germany in what is now Lower Saxony. Around winter, he recrossed the Rhine, and returned to Rome.

The following spring, Drusus (the Elder) began his second campaign across the Rhine. He first subdued the Usipetes, and then marched east to the Visurgis (Weser River). Then, he passed through the territory of the Cherusci, whose territory stretched from the Ems to the Elbe, and pushed as far east as the Weser. This was the furthest east into northern Europe that a Roman general had ever travelled, a feat which won him much renown. Between depleted supplies and the coming winter, he decided to march back to friendly territory. On the return trip, Drusus’ legions were nearly destroyed at Arbalo by Cherusci warriors taking advantage of the terrain to harass them.

Drusus was made consul for the following year, and it was voted that the doors to the Temple of Janus be closed, a sign the empire was at peace. However, peace didn’t last, for in the spring of 10 BC, he once again campaigned across the Rhine and spent the majority of the year attacking the Chatti. In his third campaign, he conquered the Chatti and other German tribes, and then returned to Rome, as he had done before at the end of the campaign season.

In 9 BC, he began his fourth campaign, this time as consul. Despite bad omens, Drusus again attacked the Chatti and advanced as far as the territory of the Suebi, in the words of Cassius Dio, “conquering with difficulty the territory traversed and defeating the forces that attacked him only after considerable bloodshed.” Afterwards, he once again attacked the Cherusci, and followed the retreating Cherusci

7

across the Weser River, and advanced as far as the Elbe, “pillaging everything in his way”, as Cassius Dio puts it. Ovid states that Drusus extended Rome’s dominion to new lands that had only been discovered recently. On his way back to the Rhine, Drusus fell from his horse and was badly wounded. His injury became seriously infected, and after thirty days, Drusus died from the disease, most likely gangrene.

When Augustus learned Drusus was sick, he sent Tiberius to quickly go to him. Ovid states Tiberius was at the city of Pavia at the time, and when he had learned of his brother’s condition, he rode to be at his dying brother’s side. He arrived in time, but it wasn’t long before Drusus drew his last breath.

Campaigns before the Clades Variana (the Varian Disaster): Campaigns of Tiberius, Ahenobarbus and Vinicius

After Drusus’ death, Tiberius was given command of the Rhine’s forces and waged two campaigns within Germania over the course of 8 and 7 BC. He marched his army between the Rhine and the Elbe, and met little resistance except from the Sicambri. Tiberius came close to exterminating the Sicambri, and had those who survived transported to the Roman side of the Rhine, where they could be watched more closely. Velleius Paterculus portrays Germany as essentially conquered, and Cassiodorus writing in the 6th century AD asserts that all Germans living between the Elbe and the Rhine had submitted to Roman power. However, the military situation in Germany was very different from what was suggested by imperial propaganda.

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was appointed as the commander in Germany by Augustus in 6 BC, and three years later, in 3 BC, he reached and crossed the Elbe with his army. Under his command causeways were constructed across the bogs somewhere in the region between the Ems and the Rhine, called pontes longi. The next year, conflicts between the Rome and the Cherusci flared up. While the elite members of one faction sought stronger ties with Roman leaders, the Cherusci as a whole would continue to resist for the next twenty years. Although Ahenobarbus had marched to the Elbe and directed the construction of infrastructure in the region east of the Rhine, he did not do well against the Cherusci warrior bands, who he tried to handle like Tiberius had the Sicambri. Augustus recalled Ahenobarbus to Rome in 2 BC and replaced him with a more seasoned military commander, Marcus Vinicius.

Between 2 BC and AD 4, Vinicius commanded the five legions stationed in Germany. At around the time of his appointment, many of the Germanic tribes arose in what the historian Velleius Paterculus calls the “vast war”. However, no account of this war exists. Vinicius must have performed well, for he was awarded the ornamenta triumphalia on his return to Rome.

Again in AD 4, Augustus sent Tiberius to the Rhine frontier as the commander in Germany. He campaigned in northern Germany for the next two years. During the first year, he conquered the Canninefati, the Attuarii, the Bructeri, and subdued the Cherusci. Soon thereafter, he declared the Cherusci “friends of the Roman people.” In AD 5, he campaigned against the Chauci, and then coordinated an attack into the heart of Germany both overland and by river. The Roman fleet and legions met on the Elbe, whereupon Tiberius departed from the Elbe to march back westward at the end of the summer without stationing occupying forces at this eastern position. This accomplished a demonstration to his troops, to Rome, and to the German peoples that his army could move largely unopposed through Germany, but like Drusus, he did nothing to hold territory. Tiberius’ forces were attacked by German troops on the way west back to the Rhine, but successfully defended themselves.

The elite of the Cherusci tribe came to be special friends of Rome after Tiberius’s campaigns of AD 5. In the preceding years, a power struggle had resulted in the alliance of one party with Rome. In this tribe was a ruling lineage that played a critical role in forging this friendship between the Cherusci and Rome. Belonging to this elite clan, was the young Arminius, who was around twenty-two at the time. Membership in this clan gave him special favour with Rome. Tiberius lent support to this ruling clan to gain control over the Cherusci, and he granted the tribe a free status among the German peoples. To keep an eye on the Cherusci, Tiberius had a winter base built on the River Lippe.

It was Roman opinion that by AD 6 the German tribes had largely been pacified, if not conquered. Only the Marcomanni, under king Maroboduus, remained to be subdued. Rome planned a massive pincer attack

8

against them involving 12 legions from Germania, Illyricum, and Rhaetia, but when word of an uprising in Illyricum arrived the attack was called off and concluded peace with Maroboduus, recognizing him as king.

Part of the Roman strategy was to resettle troublesome tribal peoples, to move them to locations where Rome could keep better tabs on them and away from their regular allies. Tiberius resettled the Sicambri, who had caused particular problems for Drusus, in a new site west of the Rhine, where they could be watched more closely.

Campaign of Varus: Prelude

Although it was assumed that the proto-province of Germania Magna, east of the Rhine, had been pacified, and Rome had begun integrating the region into the empire, there was a risk of rebellion during the military subjugation of a province. Following Tiberius’s departure to Illyricum, Augustus appointed Publius Quinctilius Varus to the German command, as he was an experienced officer, but he was not the great military leader a serious threat would warrant. Varus imposed civic changes on the Germans, including a tax – what Augustus expected any governor of a subdued province to do. However, the Germanic tribes began rallying around a new leader, Arminius of the Cherusci. Arminius, who Rome considered an ally, and who had fought in the Roman army before. He accompanied Varus who was in Germania with the three Roman legions XVII, XVIII, and XIX to finish the conquest of Germania.

Not much is known of the campaign of AD 9 until the return trip to the Rhine, when Varus left with his legions from their camp on the Weser in Germany. On their way back to Castra Vetera, Xanten, on the Rhine Varus received reports from Arminius that there was a small uprising west of Varus’s Roman camp in Germany. The Romans were on the way back to the Rhine anyway, and the small revolt would only be a small detour – about two days away. Varus departed to deal with the revolt believing that Arminius would ride ahead to garner the support of his tribesmen for the Roman cause. In reality, Arminius was actually preparing an ambush. Varus took no extra precautions on the march to quell the uprising, as he was expecting no trouble.

9

Victory of Arminius

Arminius’ revolt came during the Pannonian revolt, at a time when the majority of Rome’s legions were tied down in Illyricum. Varus only had three legions, which were isolated in the heart of Germany. Scouts were sent ahead of Roman forces as the column approached Kalkriese. Scouts were local Germans as they would have had knowledge of the terrain, and so would had to have been a part of Arminius’ ploy. Indeed, they reported that the path ahead was safe. Historians Wells and Abdale say that the scouts likely alerted the Germans to the advancing column, giving them time to get into position.

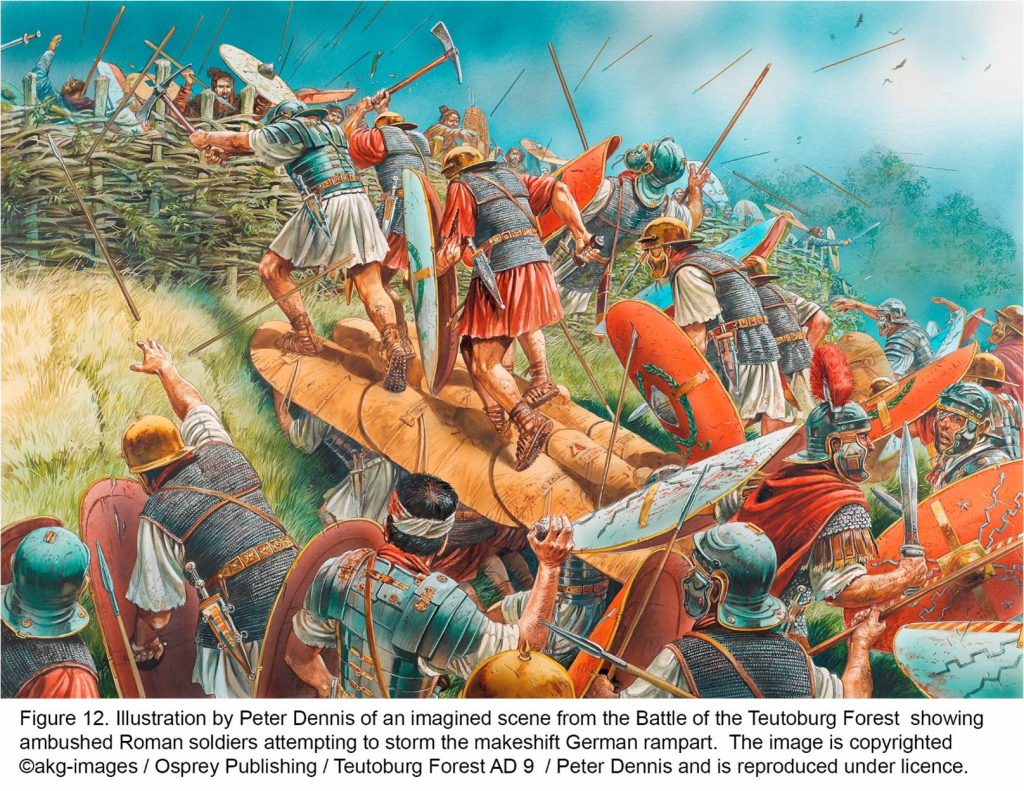

The Roman column followed the road going north until it began to wrap around a hill. The hill was to the west of the road and was wooded. There was boggy terrain all around the hill, woodland to the east, and a swamp to the north (out of sight of the Roman column until they reached the bend taking the road southwest around the hill’s northeastern point). Roman forces continued along the sloshy sandbank at the base of the hill until the front of the column was attacked. They heard loud shouting and spears began falling on them from the woody slope to their left. Spears then began falling from the woods to their right and the front fell into disorder from panic. The surrounded soldiers were unable to defend themselves because they were marching in close formation and the terrain was too muddy for them to move effectively.

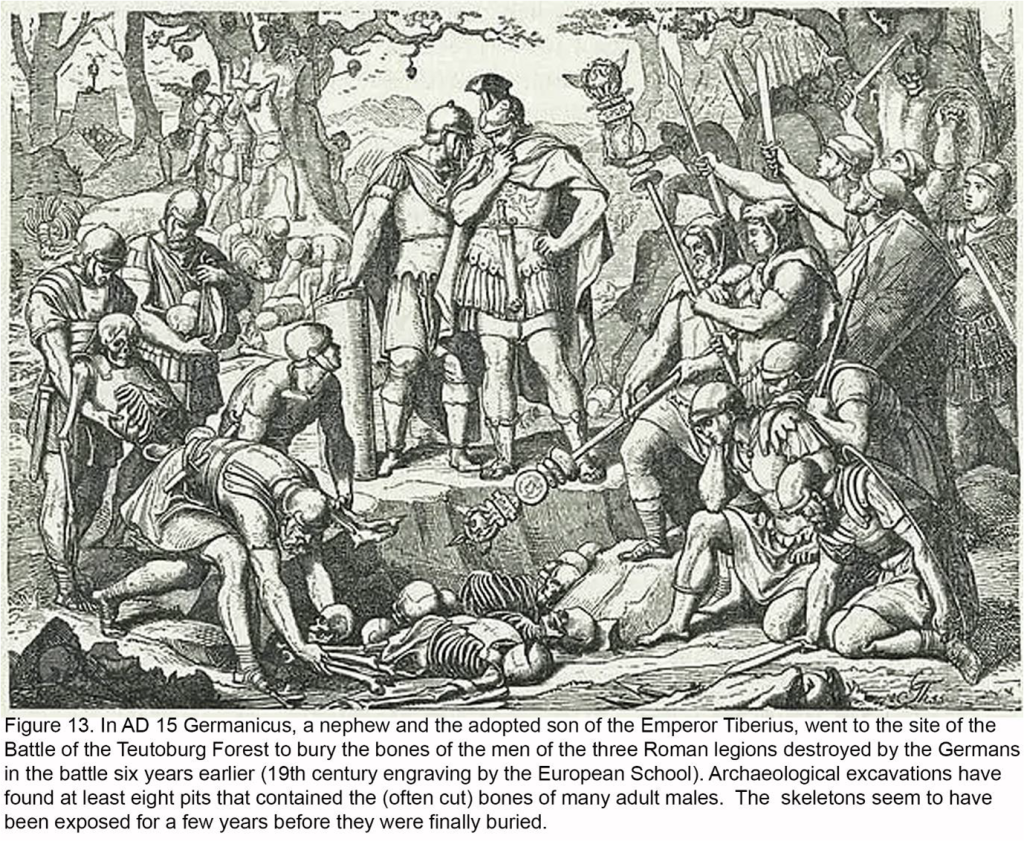

Within ten minutes, word reached the middle of the column where Varus was. Communication was hampered by the column being packed densely in the narrow road. Not knowing the full extent of the attack, Varus ordered his forces to advance forward to reinforce his forces at the front. This pushed the soldiers at the front further into the enemy, and thousands of German warriors began to pour out of the woods to attack up close. The soldiers at the middle and rear of the column began to flee in all directions, but most of them were caught in the bog or killed. Varus realized the severity of his situation and killed himself with his sword. A few Romans survived and made their way back to the winter quarters at Xanten by staying hidden and carefully travelling through the forests. Roman officers were gorily tortured and killed, and some captured Roman soldiers were kept alive as slaves of the Germans.

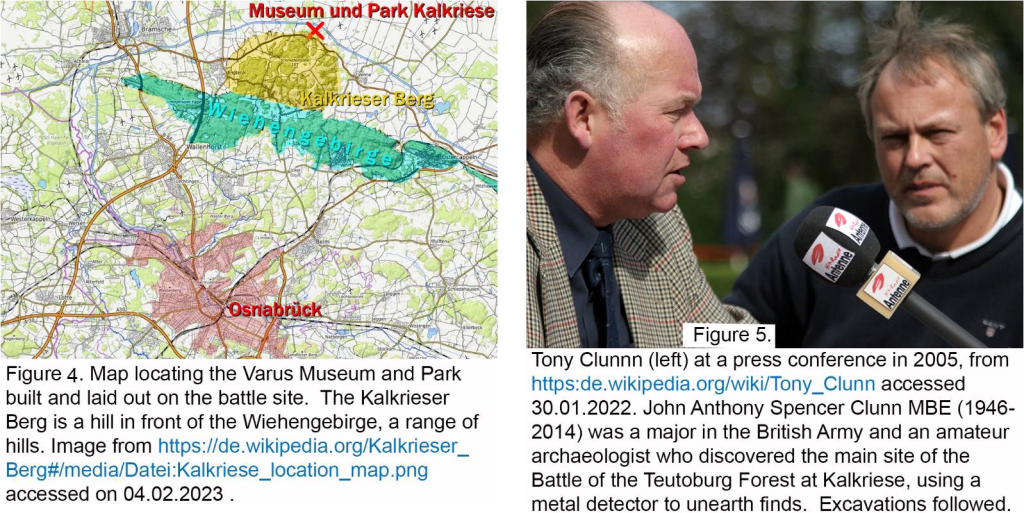

It is a rare achievement to locate the actual site of an early battle, and credit is to be given to Tony Clunn for his great achievement. The locations of the Roman victory under Suetonius Paulinus over Boudica in AD 60/61 in Britain, and the Roman victory under Agricola over the Caledonians, in Scotland, in AD 84, for instance, have yet to be found, archaeologically.

10

11

Discovery of the Battlefield (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Clunn accessed 9.02,2023)

John Anthony Spencer Clunn MBE (10 May 1946 – 3 August 2014) was a major in the British Army, and an amateur archaeologist who discovered the main site of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest at Kalkriese Hill. Clunn searched for Roman coins with a metal detector as a hobby. In 1987, when he was attached to the Royal Tank Regiment in Osnabrück, he asked Wolfgang Schlüter, at the time the archaeologist for the District of Osnabrück, where he should look. He was advised to search 20 km north of the city, where Roman coins had previously been found, though none for 18 years.

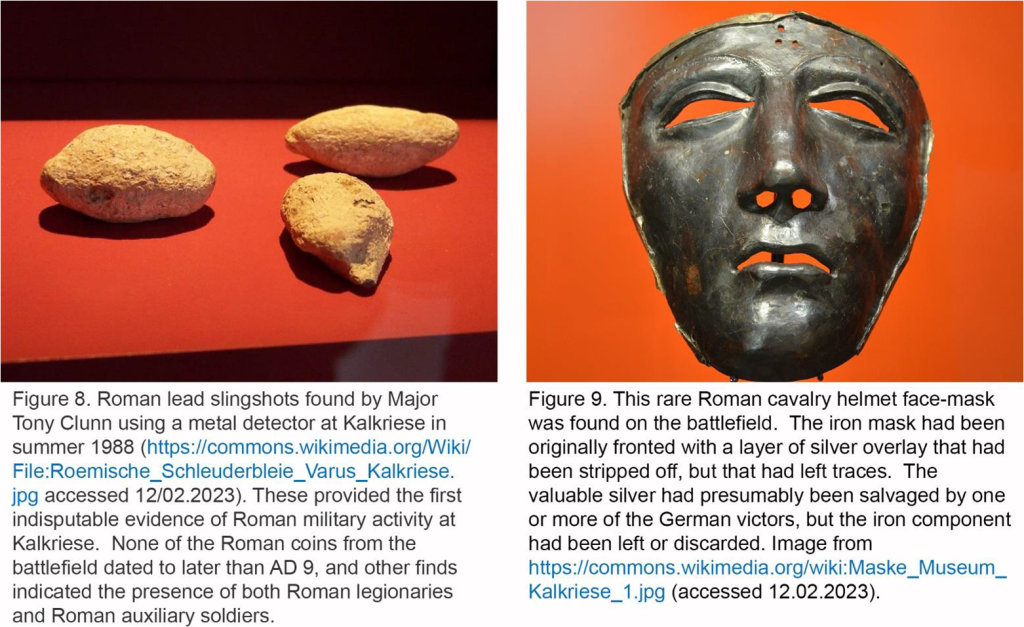

Schlüter’s recommendation was based upon a study of maps and the 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen’s proposal that the Kalkriese area was a likely location of the battle which took place in AD 9. On his first two days, in July 1987 Clunn found 105 Roman coins from the reign of Augustus (27BC – AD 14)2, mostly in excellent condition. No coins found at the site post-date AD 9. In 1988 he also discovered Roman sling shots at three locations in the vicinity of Kalkriese, the first indisputable evidence of Roman military activity there. Previously there had been many conflicting theories about the location of the battle, and scholars had searched for it without success for 600 years.

Archaeological Evidence

On the basis of Clunn’s findings, Schlüter began a comprehensive excavation of the site in 1989, later led by Susanne Wilbers-Rost. The finds are now displayed at the Varusschlacht (Varus Battle) Museum and Park Kalkriese, opened in 2002. Clunn went on to investigate the entire area around Kalkriese. The coins he discovered have made it possible to reconstruct the route taken by the Roman legionaries under Varus and to determine where they were ambushed and massacred. In Clunn’s opinion, the march route corresponds exactly to the environment described by Dio Cassius.

The archaeologists have found remains of Roman swords and daggers, parts of javelins and spears, arrowheads, slingstones, fragments of helmets, nails of soldiers’ sandals, belts, hooks of chain mail and fragments of armour plate. Other finds were less military in character, but may have belonged to soldiers nevertheless: locks, keys, razors, a scale, weights, chisels, hammers, pickaxes, buckets, finger rings. A doctor may have owned surgical instruments; seal boxes and a stylus may have been among the

12

possessions of a scribe; and a cook must have carried cauldrons, casseroles, spoons, and amphoras. Finally, jewellery, hairpins, and a disk brooch suggest the presence of women. Overall, archaeological investigations at Kalkriese have unearthed more than 7,000 artifacts, and various archaeological excavations have been ongoing there since the site was discovered by Tony Clunn in 1987-88.

Excavations show the Germans had constructed a rampart or embankment at their ambush site from which to fight the Romans. The rampart presenting as a zigzag-ging structure c. 400 m long from east to west, between two creeks. It is no longer visible above ground level due to layers of soil. Excavation work showed that the wall was erected using sod, sand, and in parts limestone. Initially, the wall measured circa 3 m in width and almost 2m in height. Today, the remaining structure is 0.3 m in height due to the levelling of the rampart and erosion, and a slight 15m wide rising can be detected. At least parts of the wall were bolstered by a wooden parapet. (Rost, Achim and Wilbers-Rost, Susanne, 2019,‘Archaeology of Kalkriese’ in Smith, C (ed) Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology https://www.academia.edu/67689095/Archaeology_of_Kalkriese?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper accessed 3rd January 2023).

13

14

15

Some sources

• Livius.org ‘Teutoburg Forest (9 CE)’ https://www.livius.org/articles/battle/teutoburg-forest-9-ce/kalkriese/ accessed 9th February 2023

• Rost, Achim and Wilbers-Rost, Susanne 2011 ‘Weapons at the Battlefield of Kalkriese’, Gladius 30:117-136 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270078400_Weapons_at_the_battlefield_of_Kalkriese accessed 4th January 2023

• Rost, Achim and Wilbers-Rost, Susanne, 2019,‘Archaeology of Kalkriese’ in Smith, C (ed) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology https://www.academia.edu/67689095/Archaeology_of_Kalkriese?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper accessed 3rd January 2023

• Tacitus Annals, Book 1, chapters 55-71 https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Tacitus/Annals/1D*.html accessed 7th January 2022

• Wikipedia ‘Battle of the Teutoburg Forest’ Battle of the Teutoburg Forest – Wikipedia accessed 9th February 2023

• Wikipedia ‘Roman campaigns in Germania (12 BC – AD 16)’https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_campaigns_in_Germania_(12_BC_%E2%80%93_AD_16)#Campaigns_of_Tiberius,_Ahenobarbus_and_Vinicius accessed 7th January 2023.

• Wilbers-Rost, Susanne, 2009 ‘Research on the Varus Battle in and around Kalkriese’, Archaeologie Online https://www.archaeologie-online.de/artikel/2009/thema-varusschlacht/forschungen-zur-varusschlacht-in-und-um-kalkriese/ accessed 4th January 2023

• Wilbers-Rost, Susanne; Großkopf,Birgit and Rot, Achim, 2012 The Ancient Battlefield at Kalkriese https://www.jstor.org/stable/26240377#metadata_info_tab_contents accessed 4th January 2023

❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖

With thanks to the contributors: Sue Loveday, Eric Morgan, Jim Nelhams & Stewart Wild

❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chairman Don Cooper 59, Potters Road, Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8440 4350),

email: chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary Janet Mortimer 34 Cloister Road, Childs Hill, London NW2 2NP

(07449 978121), email: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer Roger Chapman, 50 Summerlee Ave, London N2 9QP (07855 304488),

email: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec. Vacancy

Website: www.hadas.org.uk

16