No. 650 May 2025 Edited by Dudley Miles

HADAS DIARY – Forthcoming Lectures and Events

Tuesday 13 May 2025 Les Capon (AOC Archaeology), A community / HLF excavation at Cranford, Hillingdon with trenching over four seasons that discovered Romano-British roundhouses, Saxon Houses, medieval and Tudor and post-medieval remains and intact cellars. Encompassing the Bronze Age to the 19th Century.

Weekend of 7th-8th June 2025 It’s back! Barnet Medieval Festival at Lewis of London Ice Cream Farm, Galley Lane, Barnet, Herts EN5 4RA Note new venue – not Barnet Rugby club as before due to redevelopment. https://barnetmedievalfestival.org/

Tuesday 10 June 2025 – 7.30 pm Annual General Meeting to be followed by a lecture by our president, Jacqui Pearce,

Lectures held in the Drawing Room, Avenue House, 17 East End Road, Finchley N3 3QE. 7.45 for 8pm.

Buses 13, 125, 143, 326, 382, and 460 pass close by, and it is a five-ten-minute walk from Finchley Central Station on the Barnet Branch of the Northern Line where the Super Loop SL10 express bus from North Finchley to Harrow also stops.

Tea/Coffee/biscuits available for purchase after each talk.

Mapping the kingdom

Our last talk was by Hugh Petrie, looking at the colourful maps of the first County Series, which were one of the greatest feats of the Victorian period. The lecture is the story of the first large scale survey of England made in the 1860s at “1:2500 OR 25.344 INCHES TO THE MILE.” The lecture looks at how and why the survey was carried out, the people who made it happen from the labourers, through to the sappers and officers of the Royal Engineers, and how the maps can be used to tell us about local history, using maps from the local studies collection of the London Borough of Barnet.

This is follow up material that people asked for

National Library of Scotland – 25″ Maps of England and Wales

https://maps.nls.uk/os/25inch-england-and-wales/

Barnet Open Data/History – Ordnance Survey from Barnet Local Studies collection

https://open.barnet.gov.uk/dataset/2rpm1/barnet-history

The Ordnance Survey of Great Britain, its history and object, Josiah Pierce. THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE, Vol. II. 1890.No. 4.

1

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/62827/62827-h/62827-h.htm#chap2

History of the Ordnance Survey W. A. Seymour (editor)

William Dawson & Son Ltd. Crown Copyright 1980

https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/documents/resources/os-history.pdf

Ordnance Survey – Map Makers to Britain since 1791

Tim Owen & Elain Pilbeam, Ordnance Survey HMSO 1992

www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/documents/resources/map-makers-britain-history.pdf

Lincoln Janet Mortimer

I spent a weekend recently in Lincoln with fellow HADAS member, Barbara Thomas. For anyone interested in history or archaeology, Lincoln is the perfect place to visit. Our taxi from the station took us through the 11th century East Gate to the Lincoln Hotel where we were staying and greeting us in the front of the hotel was the remains of the Roman east gate. Some people may have been dismayed to find that the view from their hotel room was a wall but we were thrilled to find that our view was of a large section of Roman wall.

On the first day we had a guided tour of the Guildhall where we were given a talk on the history of Lincoln as well as that of the Guildhall. The building, dating from the 16th century, was interesting and we saw some of their treasures including the sword of Richard II and several royal charters.

On the second day we participated in a 3 hour guided walking tour. Amazingly this was a free tour although we had to book in advance. We did wonder whether we would be able to complete the full three hours but the guides were so interesting and informative about Lincoln’s history that this was no problem.

The following day we started off at the castle where we joined another guided tour. By this time I had absorbed so much knowledge of the history of Lincoln that I could be considering a new career as a tour guide. Lincoln dates back to the Iron Age but became important in Roman times when Lindum Colonia became the portmanteau word Lincoln. After the Norman Conquest, the important strategic position of Lincoln was recognised and a castle and cathedral were built. Over the years the fate and fortunes of Lincoln waxed and waned but the locals seem particularly fond of the tale of the Battle of Lincoln Fair where a possible further French takeover at the invitation of the Barons was halted in 1217. After our castle talk, we walked the castle walls where the views were spectacular. We also visited the Victorian prison in the grounds which was grim but very interesting. We saw the Magna Carta and two copies of the Charter of the Forest, which was probably more important than the Magna Carta to the common man.

Later we visited the wonderful cathedral. This impressive building was started in 1072 and has a magnificent stained glass window to rival the rose window in Notre Dame. The cathedral has even doubled as Notre Dame in films. For 200 years it was the tallest building in the world, even taller than the Great Pyramid, until one of the spires collapsed in 1548. It is also home to the heart of Queen Eleanor, wife of Edward I as, odd as it may seem today, parts of her were distributed around the country following her death. When we were there we were lucky enough to witness them setting up a table made from an ancient Fenland Black Oak. These giant trees date from around 5,000 years ago before the pyramids, and are now extinct but the 44ft length of this one was found in farmland in Norfolk and preserved and made into this impressive table.

2

Who killed King Edward the Martyr? Dudley Miles

When Edgar, King of the English, died in 975, he left two sons by different wives. Edward was around thirteen years old. Almost nothing is known about his mother and even her name is not recorded in any surviving document until after the Norman Conquest. By contrast, his younger half-brother, the future King Æthelred the Unready, was the son of Ælfthryth, a powerful figure who was the only woman known to have been crowned Queen of England in the tenth century.

The succession to the throne was disputed by supporters of the two princes, and the events were described around 1100 by Byrhtferth of Ramsey. Ælfthryth naturally backed her son, and some magnates supported him because, according to Byrhtferth “he seemed more gentle to everyone in word and deed. But the elder son struck not only fear but even terror into everyone; he hounded them not only with tongue-lashings but even with cruel beatings – and most of all those who were members of his own household.” But Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, supported Edward, and his voice was decisive.

Edward only reigned for three years. On 18 March 878 he arrived at the Gap of Corfe, now Corfe Castle village, to visit Ælfthryth and Æthelred, who were living on her estate there. According to Byrhtferth, the magnates and leading men had decided to murder Edward, which they did by stabbing him while he was still on his horse. His body was then taken by his thegns (noble retainers) to the house of a churl, where it spent the night covered in a cheap blanket, and was then buried without any honour.

Contemporaries were deeply distressed at the manner of his death. Kings were seen as sacred, and those who died by violence were commonly regarded as saints. No one was punished for the killing and no pre-Conquest source names the killers, but post-Conquest chroniclers and some modern historians accuse Ælfthryth of responsibility for the murder. Æthelred proved to be an ineffective king and England was conquered by Danish Vikings in the early eleventh century. His disastrous reign was seen by these writers as partly a result of the suspicious circumstances of his accession. This view has been challenged by historians who point out that there is no evidence that contemporaries blamed Ælfthryth or Æthelred for Edward’s death.

No modern historian blames Æthelred personally for the killing in view of his youth, but most think that Edward was murdered by supporters of Æthelred in the hope of personal advantage. An exception is Ann Williams, who suggests that in view of Edward’s violent temper, he may have been accidentally killed in an affray with Ælfthryth’s retainers.

This theory is supported by several points. Byrhtferth wrote that Ælfthryth and Æthelred stayed in the house when Edward arrived, but it is unlikely that they would have been so disrespectful as not to greet their king. It is more plausible that Byrhtferth concealed their presence so as not to implicate them. Byrhtferth claimed that Edward was visiting his beloved brother, but it is unlikely

3

that a youth of Edward’s character would have been a close friend of a rival for the throne. It is more probable that he called to pursue a quarrel with Ælfthryth. He may have lost his temper and tried to violently assault her, and been accidentally killed by her retainers who were trying to protect her.

The strongest support for the accident theory is provided by Byrhtferth’s description of the conduct of Edward’s thegns. The highest duty of a man in Anglo-Saxon culture was loyalty to his lord, and one of the greatest Old English poems was The Battle of Maldon, about the defeat of an English army by the Vikings in 991. The poem celebrates the heroism of warriors who chose to die fighting after the fall of their commander, Ealdorman Byrhtnoth, rather than desert their dead lord. Disloyalty to a king was even more shameful, and it is extraordinary that Edward’s thegns did not fight for him and treated his body with contempt. It seems that they did not blame the men who killed him, and that there was a general feeling of relief at the death of a violent youth, who may have been unbalanced to the point of being mentally ill.

The kingdom’s magnates were probably relieved at Edward’s death and at first they made no effort to retrieve his body for honourable burial, but popular horror at the violent death of a king forced them to change their minds. A year later, his body, or a body which could be passed off as his, was ceremoniously conveyed to Shaftesbury Abbey for royal burial. He soon came to be revered as a saint, and King Æthelred took the lead in promoting his half-brother’s cult, which became important in the late Anglo-Saxon period. Popular reverence for Edward forced Byrhtferth to portray his death as a foul murder, but the condemnation of his character, and description of the conduct of his thegns when he was killed, may have been intended to hint at the truth.

The cult of Edward the Martyr cult declined after the Norman Conquest, but revived in the later Middle Ages, and there are still churches dedicated to him in Corfe Castle, Goathurst in Somerset, Cambridge, Castle Donington and New York. The historian Tom Watson comments: “For an obnoxious teenager who showed no evidence of sanctity or kingly attributes and who should have been barely a footnote, his cult has endured mightily well.”

Sources

Lapidge, Michael, ed. (2009). Byrhtferth of Ramsey: The Lives of St Oswald and St Ecgwine, pp. 122-145

Williams, Ann (2003). Æthelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King, pp. 1-17

Watson, Tom (2021). “The Enduring Cult of Edward the Martyr”. Southern History. 43, p. 19

For other sources, see the Wikipedia article Edward the Martyr – Wikipedia.

I thank Dr Ann Williams for helpful comments on the article.

Explorator Peter Pickering

Readers of this newsletter may like to know of a way of keeping up to date with archaeology throughout the world. I have long been a subscriber (free) to a weekly email called ‘Explorator’ from David Meadows, who is, I think, based in Canada. He looks at a very wide range of newspapers and periodicals, picks out items of archaeological interest, summarises them and includes a link. The link does not always work for me (there may be some sort of a pay wall operating) and sometimes opening the link produces more advertising than content. But just skimming the summaries (those on similar subjects are brought together) keeps me up to date with what is happening in archaeology throughout the globe. To subscribe to Explorator, send a blank email message to explorator+subscribe@groups.io.

Transport Corner – Trolleybus demise Andy Simpson

Many readers will be aware of my interest in historic road transport, which often leads me to the magazine racks in remaining branches of W H Smith – the Victoria Station branch in particular currently has probably the best selection of transport titles in London!

4

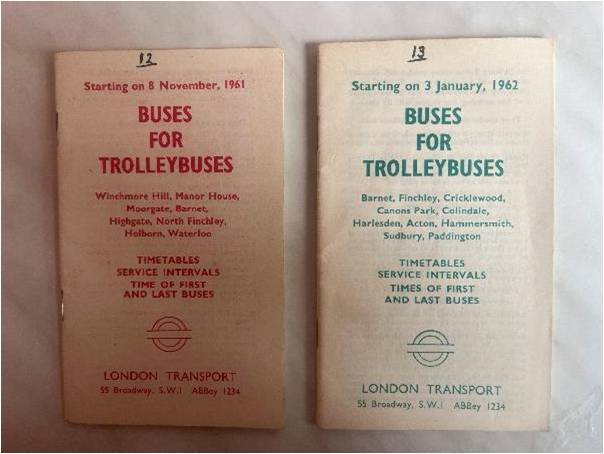

Last year, this led me to the October-November 2024 edition of Classic Bus magazine and an article by local resident Hugh Taylor ‘removing the trolleybus overhead’ partly illustrated by photos taken in Colindale and Edgware in March 1962.

Electrically powered Trolleybuses ran to Barnet via Golders Geen and Finchley, and Canons Park and Edgware via Cricklewood and Colindale, until the bitterly cold and snowy night of 2/3 January 1962, known to enthusiasts as ‘snowy thirteen’ in the aftermath of heavy and disruptive snowfall on New Year’s Eve – the thirteenth of fourteen stages of conversion of London trolleybus routes to motorbus operation at roughly three-month intervals, beginning in March 1959, when scrapping of redundant trolleybuses at Colindale began in earnest. Some readers will still recall the 609, 645, 660, 662, 664, 666 and other local trolleybus services running from Barnet and Edgware.

Colindale tram depot on the Edgware Road (known as Hendon depot until July 1950 and renamed to avoid confusion with the former Hendon motorbus garage on the Burroughs) had already seen trolleybus experiments back in 1909, and trolleybuses replaced trams on the Edgware Road from Edgware to Hammersmith in July 1936. It could accommodate 48 trolleybuses. Trams still ran via Finchley to Barnet until March 1938 when replaced by the 609 and 651 trolleybuses to Moorgate.

The conversion date for these routes had been brought forward from the originally intended date of 31 January 1962; as the most profitable trolleybus routes there was reason for leaving them till last – at one time it was intended to operate them until July 1962 until the addition of the Fulwell and Isleworth routes to the conversion programme when their modern Q1 vehicles were sold to nine Spanish operators in 1961, where the very last ones ran in Coruna until 14th January 1979.

Last movements under power were Class N1 trolleybus No.1564 on route 645 from Barnet to Cannons Park, leaving Barnet in the closing minutes of 2 January and entering Colindale depot at 12.40am on Wednesday 3 January 1962, having been ceremonially towed in by crews five minutes earlier to mark the last run and the closure of the depot. It was preceded in the first few minutes of 3 January by No.1569, the last service trolleybus to run through Burnt Oak Broadway. No.1468 on route 660 was the last vehicle into Finchley depot early on 3 January 1962, escorted in by staff using fog flares to create a torchlight procession; at around 1am on 3rd January it was also the last trolleybus to leave Finchley Depot, running to Fulwell depot for further service.

No. 1658 was the last southbound via Colindale to Stonebridge depot. No.1666 was the last trolleybus to operate on the Edgware Road wires in the borough, running along with 1616 from Stonebridge depot to Colindale depot for storage on the night of 3/4 January 1962. It had been the last trolleybus of stage 13 when it entered Stonebridge depot at 12.45am on 3 January after its run in from Finchley.

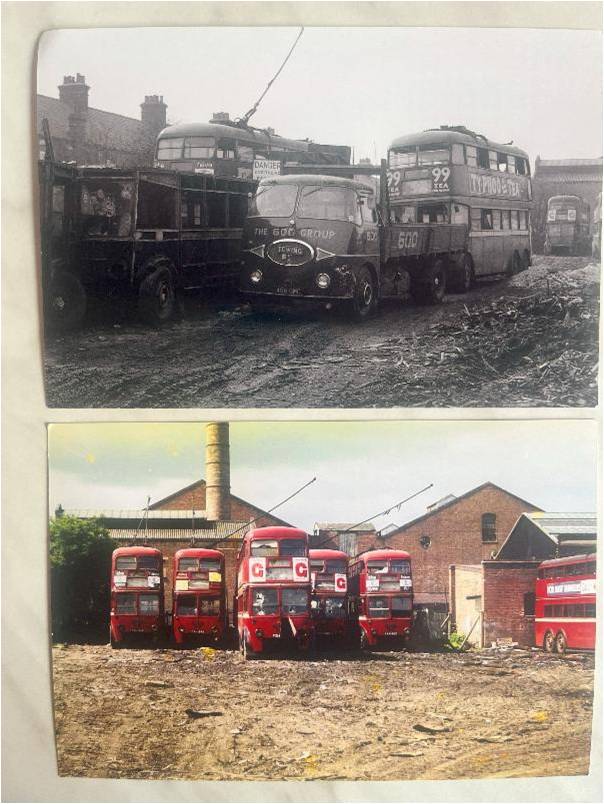

After that the power was cut off, 108 trolleybuses were withdrawn from service and the traction poles and the 29.37 miles of overhead they supported awaited demolition by contractors George Cohen & Sons’ 600 Group, who also purchased the vehicles, Following running of the last London trolleybuses in the Wimbledon area on Tuesday 8 May 1962 (the last trolleybus of all, No.1521, entering Fulwell depot at 1.30am the following morning) they were towed one by one to the yard at the rear of Colindale depot, the last, No. 1658, on 18 July 1962, and all scrapped by early September 1962, having been sold to Cohens for around £106 each. Class N2 trolleybus No. 1653 being the very last to be scrapped following its sale to Cohens that July. The depot itself was demolished in 1965; the last vehicles actually in the depot itself were removed to the yard to await scrapping on 19 February 1962, after which the depot wiring was removed by London Transport staff.

5

The copper overhead running wires had a scrap price of £232/10s a ton. London Transport paid Cohens £94/15s per route mile to remove the overhead and fittings on double track routes such as the Edgware Road, half that on single track such as that at Hampstead Heath. LT then sold the same items to Cohens for £839 per route mile for what they had removed, who then sold it for an even higher price for profit. They were allowed six months to demolish each section, with the last overhead of all cut down in Shepherd’s Bush around 18th September 1962.

The traction poles were similarly handled with LT paying Cohen’s to remove them and then sold them back to them. It took three and a half years to scrap 1,567 trolleybuses, dismantle 254 miles of overhead and around 23,000 traction standards! 5000 were sold to local councils such as Hendon for use as lighting standards, traffic light supports etc, which explains their survival in places like Golders Green and Temple Fortune into the 1970s and Friern Barnet Road until around 1990; these were recorded in November 1978 and illustrated in the June 1980 HADAS newsletter. Others, which survived in Temple Fortune into the 1970s, are recorded photographically on HADAS index cards.

By 2024 only five remained in situ in the whole of London, our nearest being at Stonebridge Park depot.

Cohen’s worked at night to cut down the main line overhead. The wires at Edgware and Cannons Park were cut down on 9 March 1962, and in the early hours of Saturday 10 March 1962 Cohen’s men cleared the southbound section between Colindale and Cricklewood; this still left parts of the former Edgware terminus wiring intact the following day. The last stage 13 overhead was not removed until 8 May 1962, in the Acton Vale area – the same night the last London trolleybus of all ran into Fulwell depot.

Other sources referred to for this article include various issues of the London Omnibus Traction Society’s invaluable London Bus Magazine, the London Trolleybus Preservation Society’s Trolleybuses in North-West London – A Pictorial Survey (1987), Mick Webber’s The Final Chapter – The End of the London Trolleybus System (2016), Keith Farrow’s London Trolleybus Wiring South East & North West (1985), Finchley trolleybus driver Charlie Wyatt’s Beneath The Wires of London (Capital Transport, 2008) and the London Borough of Barnet, The London Trolleybus, published in conjunction with an exhibition at the former Church Farm Museum in 1979.

6

Original photographers unknown; from A. Simpson collection.

7

The Cultural Significance of the Sutton Hoo Helmet David Willoughby

The Sutton Hoo helmet is considered by many to be the most iconic artefact excavated from the Sutton burial field in Sutton Hoo, Suffolk.

The helmet was discovered in a fragmentary state in mound 1 at the site. This mound contained an Anglo-Saxon ship burial, which from the coins within, has been dated to the early 7th century. Also found were other high status grave goods including a sword hilt, a sword, a shield, belt fittings, clasps, a gold buckle, a purse lid, drinking horns, a hanging bowl, a lyre and two Byzantine spoons inscribed with the name of the apostle Paul.

The burial site is close to the river Deben and four miles from the former East Anglian royal centre at Rendlesham. It is thought that the occupant of mound was a member of the East Anglian royal dynasty (the Wuffingas), most likely the king Rædwald (although his son Rægenhere is one amongst other possible candidates) (Marzinzik, 2007). King Rædwald was the first king of East Anglia to convert to Christianity but was influenced by his wife to maintain a pagan shrine alongside a Christian altar (Bede, 731). No matter who the occupant of the burial was he was clearly buried at a time when pagan beliefs were being increasingly replaced by those of Christianity.

The helmet itself, once reconstructed, revealed that the dome had been constructed from a single sheet of iron surmounted by a crest consisting of a hollowed tube of iron inlaid with silver wire. This crest is in the form of a snake with a gilt bronze head at either end. The heads have open mouths equipped with jagged teeth and are set with garnets for eyes. The helmet also has a neck guard, two hinged cheek pieces and an ornate face mask. The face mask is adorned with silver inlaid gilt-bronze eyebrows, nose and moustache. At the base of each eyebrow are inlaid a row of garnets, and those on the proper right side only, are backed with gold foil to increase their brilliance. The brows also differ slightly in length and in the colour of their gilding. At the top of the nose is a head similar to the snake head on the crest which it faces. Together these adornments form the impression of a dragon-like creature, with the eyebrows forming the wings, the nose the body and the moustache the tail (Brunning, 2021). At the end of each eyebrow is the figure of a boar’s head with tusks.

The entire surface of the helmet (dome, cheek guards and facemask) is coated with tinned bronze and embossed with ornate repoussé work. The surviving reliefs consist of intertwined zoomorphic designs on the face mask and, on the cheek guards and dome four differing designs in square plaques, three of which have been reconstructed. The first is another intertwined zoomorphic pattern, the second consists of human figures with spears and swords wearing horned headdresses with the horns having terminals in the form of serpent’s or bird’s heads. These figures appear to be dancing. The third design shows the figure of a mounted warrior riding down an adversary who is plunging a sword into the horse’s flank whilst another small figure grips the shaft of the mounted warrior’s spear. Each design is repeated over more than one plaque.

The helmet is estimated to have weighed 2.5 kg and was larger than its wearer’s head. There is evidence it was padded out with leather (Bruce-Mitford, 1979). It is not clear if this helmet was intended for use in battle or whether it was only a parade helmet (Brunning, 2021).

8

The helmet’s only parallel in Anglo-Saxon England is the Staffordshire helmet which is awaiting full restoration. There are parallels however with Vendel and Valsgärde helmets of the same period discovered in the Uppland province of Sweden, north of Stockholm. The construction of these helmets differs from that of the Sutton Hoo helmet, but the adornments are strikingly similar (Brunning, 2021). Even though it is possible that Scandinavian smiths in East Anglia may have helped craft the helmet (Marzinzik, 2007) it is regarded as showing distinctive Anglo-Saxon features (Brunning, 2021). It is thought that all these helmets were influenced by late Roman helmets, perhaps brought back by Germanic mercenaries (Marzinzik, 2007), and the double headed snake crest on many may even have been derived from the classical amphisbaena (King, 2015). Although the Wuffinga dynasty traced their ancestry back to Sweden (Bruce-Mitford, 1979), it is not clear whether the Swedish helmets influenced the design of the Sutton Hoo helmet or whether all were influenced from elsewhere in Scandinavia (Wolf, 2015). Certainly it is more likely that Roman helmets would have been encountered by the peoples of Northern German and Denmark rather than those of Northern Sweden. What is apparent though, from the Sutton Hoo helmet and other grave goods, is that East Anglia traded with and was subject to cultural influences from Scandinavia and beyond.

In the first century AD the Roman historian Tacitus described the pagan heroic ideal in Germanic culture (Tacitus, 98 AD). This ideal was still extant in Anglo-Saxon society at the time of the helmet’s burial. This ideal manifested itself in warriors pledging their loyalty and lives to the service of their lord in return for his protection and his giving of sumptuous gifts.

Clearly the wearer of this helmet would have been a wealthy and powerful individual worthy of the loyalty of his war band. The helmet itself not only speaks to the man’s wealth and ability to give rich gifts, but in itself may have been a symbol of power and authority, equivalent to a royal crown. The dragon motif on the face guard may in have been a statement of the wearer’s wealth as in Beowulf a dragon is portrayed as a guardian of a rich treasure hoard. Certainly Rædwald is described by Bede as a very powerful king (Bede, 731) and in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle he is described as ‘Bretwalda’ (overlord).

The wearer of the helmet, which would have been a very rare object at the time, would have seemed almost unworldly, perhaps god-like. This would be compounded by the size of the helmet and the fact that the wearer would be able to project his voice from within. The creatures adorning the helmet are all fearsome and represent characteristics to which any warrior would aspire. They would convey to any enemy that to mess with the wearer would be to ask for trouble. The wearer himself would have had his senses dulled by the helmet and this may have given him a sense of being transported to another world or becoming another being (Brunning, 2021).

Many of the features of the Sutton Hoo Helmet are described in the epic Beowulf: ‘war-masks’ (line 2257), ‘cheek-hinged helmets’ (line 335), ‘Boar shapes flashed above their cheek-guards’ (lines 303-304) and ‘the head-guard wound with wires’ (lines 1030-1031). All of the helmets described are worn by heroic figures in the poem and the possessor of the helmet would almost certainly have associated themselves with the heroic ideals expressed in epic poetry.

The deposition of the helmet in a ship burial in itself indicates pagan ritual with the intention that it be used in the afterlife or perhaps to conserve or secure status in the next world. Burials with such a rich grave goods are a feature of the early 7th century and reflect the development of society into one with established hierarchies and for families who may have been insecure in their succession the opportunity to demonstrate their wealth and power and their fitness to rule (Wolf, 2015).

The symbols and motifs on the helmet strongly suggest non-Christian belief (although it is possible that the animal forms on the helmet may together represent the tria genera animantium of the book of Genesis and that the helmet could have been a baptismal or conversion gift (King, 2015)). It has been suggested that the interlaced designs on the helmet, apart from decoration, were a way of

9

guarding against evil by literally tying it up in knots (Marzinzik, 2007) and were also adopted by powerful elites to display their wealth and identity (Taylor, 2020).

The subtle differences between the two eyebrows of the face mask would make the proper right eye area stand out under certain lighting conditions (for example in a fire-lit mead hall) giving the illusion that the wearer of the helmet was blind in one eye and therefore be seen as both a war leader and a personification of Woden (the god in mythology sacrificed an eye in exchange for wisdom) (Price & Mortimer, 2014). It might also signify that the wearer of the helmet was able to invoke Woden’s protection or take on his strength (Brunning, 2021).

The figure of a horseman riding down a foe is strongly reminiscent of Roman reliefs. However, the stabbing of the horse by the fallen figure and the small figure grasping the shaft of the horseman’s spear are Scandinavian ideas (Brunning, 2021). The meaning is of the scene uncertain but it has been suggested that this might be the depiction of a Germanic battle tactic described by the Roman historian Marcellinus where warriors would deliberately get under horses so they could kill the horse and bring down the rider (Marcellinus, 378 AD).

The relief of two figures with spears and swords and who are wearing horned headdresses are a motif that has close parallels in Scandinavia. The figures are believed to be performing a ritual dance prior to going into battle. This may be the dance described by Tacitus (Tacitus, 98 AD). A very similar figure which occurs alongside a man in wolf skin (assumed to be a berserker) on one of the bronze Torsunda die plates, found in Sweden, has been shown to be one eyed and is thought to represent Woden. The dance depicted on the Sutton Hoo helmet may therefore be associated with the cult of Woden (Marzinzik, 2007). The boar’s head motif not only features on helmets in Beowulf but has been found on other excavated Germanic helmets most notable the Bentey Grange Anglo-Saxon helmet found in Derbyshire. The boar motif was believed to convey protection to the wearer of the helmet and to make the helmet impenetrable (Brunning, 2021).

The crest with its two terminal heads, could have been thought to offer supernatural as well as physical protection. In classical times the twin headed Amphisbaena was reputed to offer power and protection (Allardice, 1990).

The likely associations on the helmet with Woden may have served to reinforce the Wuffingas dynasty’s right to rule and their claimed lineage back to Woden (Anonymous). The Sutton Hoo helmet tells us much about the culture of early 7th C Anglo-Saxon East Anglia, It tells of a royal dynasty exhibiting their wealth, power and right to rule. It tells of the heroic culture of the time and the relationship of a leader with his warriors. It also tells of the fine art produced and links with Scandinavia and with epic poetry. It also hints at the belief system and particularly the cult of Woden with his links to the Wuffingas dynasty.

References

Allardice, P. (1990). Myths, Gods, and Fantasy. New York: Avery Publishing Group, Inc.

Anonymous. (n.d.). Textus Roffensis, version R manuscript. The Anglian Collection.

Bede, T. V. (731). Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum.

Bruce-Mitford, R. L. (1979). The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial: A Handbook. London: British Museum Publications.

Brunning, S. (2021, January 14th). British Museum Curator’s Corner: Sue Takes on the Sutton Hoo Helmet. Retrieved March 18th, 2021, from YouTube: Sue Takes on the Sutton Hoo Helmet | Curator’s Corner S6 Ep5 #CuratorsCorner #SuttonSue #TheDig – YouTube.

King, M. (2015). Sutton Hoo: fantastic creatures as servants of Christ? In Il fantastico nel Medioevo di area germanica (pp. 17-34). Edipuglia.

Marcellinus, A. (378 AD). Res Gestae Book XVI, Chapter 12.22.

Marzinzik, S. (2007). The Sutton Hoo Helmet. The British Museum Press.

Price, N., & Mortimer, P. (2014). An Eye for Odin? Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo. European Journal of Archaeology, Volume 17 , Issue 3 , 517 – 538.

10

Tacitus, P. C. (98 AD). De origine et situ Germanorum.

Taylor, A. (2020). The Art of the Staffordshire Hoard. Retrieved from Stoke-on-Trent Museums: The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery: https://www.stokemuseums.org.uk/pmag/the-art-of-the-staffordshire-hoard/

Wolf, A. (2015). Sutton Hoo and Sweden revisited. In E. E. A. Gnasso, The long seventh century: continuity and discontinuity in an age of transition (pp. 5-17). Peter Lang.

Other Organisations / Societies’ events Eric Morgan

As always please check with the societies’ websites before planning to attend since not all societies and organisations have returned to pre-covid conditions.

Correction: The item shown in the April Newsletter as Wednesday 19th May for Enfield Society should be Monday, 19th May.

Wednesday 28th May, 7.45 pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society. North Middlesex Golf Club, The Manor House, Friern Barnet Lane, London, N20 0NL. Camden Town. Talk by Paul Baker (Barnet Local History Society and City of London Guide). Please visit www.friernbarnethistory.org.uk for further details. Non-members £2. Bar to be available.

Thursday 29th May, 7 pm. Stephens’ House and Gardens. 17 East End Road, London. N3 3QE. Guided Tour. A summer evening guided tour of the Main House and its gardens (including the Bothy Garden. Tickets £15 including a glass of wine. Members £13. To book please visit www.stephenshouseandgardens.com.

Tuesday 3rd June, 11 am. Enfield Society, Jubilee Hall, 2, Parsonage Lane, Junction Chase Side, Enfield, EN2 0AJ. A Walk down Memory Lane and beyond. Talk by Colin Barratt (Friern Barnet L.H.S.) on an imaginary walk along a number of main roads in Southgate, Winchmore Hill and Oakwood, looking at historical buildings, places and people. Non-members charge £1 the door. Please visit www.enfield.org.uk.

Saturday 7th June, 12-5 pm. Highgate Festival, Pond Square and South Grove, Highgate Village, London. N6 5BS. Lots of stalls including Highgate Society and Highgate Literary and Scientific Institute. Also craft, books and clothes, stalls and music stage. Free. Also Tower Tours of Church.

Monday 9th June, 3 pm. Barnet Museum and Local History Society. St. John the Baptist Church, Chipping Barnet, corner High Street/Wood Street, Barnet, EN5 4BW. Behind The Battle of Barnet Banners. Talk by Scott Harrison. For Further information please visit www.barnetmuseum.org.uk.

Friday 13th June, 7.30 pm. Enfield Archaeological Society. Jubilee Hall (Address as for Enfield Society – Tuesday 3rd June). Roman Egypt. Talk by Stefania Afarano (U.C.L). Please visit www.enfarchsoc.org.uk. for further details. Visitors charge £1.50. Refreshments, Sales and information to be available.

Friday 20th June, 7.30 pm. Wembley History Society. St. Andrew’s Church Hall, (behind St. Andrew’s new church), Church Lane, Kingsbury, London. NW9 8RZ. Frankenstein – Food, Fun, Family and more. Talk by Lester Hillman. Visitors charge £3. Refreshments to be available in the interval.

Sunday 22nd June 12 -6 pm. East Finchley Festival. Cherry Tree Wood, East Finchley, N2 9QH. (Entrance off High Road, opposite Tube Station). Lots of stalls including Finchley Society, Friends of

11

Cherry Tree wood (Roger Chapman, HADAS), North London U3A. Also craft and food stalls and music stages.

Wednesday 25th June, 7.45 pm. Friern Barnet and District Local History Society. North Middlesex Golf club (address as for Wednesday 28th May). Transport for London. Talk by David Le Boff, Non-members charged £2.

Thursday 26th June, 7.30 pm. Finchley Society. Drawing Room, Avenue (Stephens) House. (Address as for Thursday 29th May). Annual General Meeting. For further details please visit www.finchleysociety.org.uk. Charge £2.

Friday 20th – Sunday 29th June. Hampstead Summer Festival including Friday 20th – Art Street canvases in Keats Grove, London, NW3 2RS for a month. Sunday 22nd Art Fair 12 – 5 pm. In Keats’ House Garden, 10 Keats Grove, London. NW3 2PR. Free entry. Please see www.hampsteadsummerfestival.org.uk.

Saturday 21st – Sunday 29th June. Proms at St. Jude’s Music and Literary Festival. Central Square, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London. NW11 7AH. Including Talks and Heritage Walks. For full details please visit www.promsatstjudes.org.uk. Tickets for guided walks must be booked in advance.

Thanks to our contributors this month: Dudley Miles, Eric Morgan, Janet Mortimer, Hugh Petrie, Peter Pickering, Andy Simpson, David Willoughby

Hendon and District Archaeological Society

Chair Sandra Claggett, c/o Avenue House, 17 East End Road, Finchley N3 3QE

email : chairman@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Secretary Janet Mortimer 34 Cloister Road, Childs Hill, London NW2 2NP

(07449 978121), email: secretary@hadas.org.uk

Hon. Treasurer Roger Chapman, 50 Summerlee Ave, London N2 9QP (07855 304488),

email: treasurer@hadas.org.uk

Membership Sec. Jim Nelhams, 61 Potters Road, Barnet EN5 5HS (020 8449 7076)

email: membership@hadas.org.uk

Website: www.hadas.org.uk

12